In California, vulnerable Republicans are backing away from hard-line immigration stances

- Share via

For years, Orange County Republicans such as Reps. Ed Royce and Mimi Walters have drawn from a familiar GOP playbook on immigration.

Walters campaigned saying that people who enter the U.S. illegally “should not be rewarded,” and she has voted at least three times against protections for immigrants who were children when they were brought here illegally. Royce once decried the Dream Act, which would have given those young people a path to citizenship, as “amnesty” and said illegal immigrants would take the spots of American university students.

But when President Trump announced last month that he would end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, or DACA, Royce sympathized with “children who have only known America as their home,” and Walters said it would be “unjust to punish them.” Both called on Congress to find a permanent solution for DACA recipients, though neither have signed on to one.

The backpedaling is indicative of the kind of shift that has been underway in their districts for years. The two represent more than 40% of voters in Orange County, longtime Republican turf that last year went to a Democrat for president for the first time in 80 years. That transformation is due mostly to the explosive growth of Latinos, Asians and other minority communities that tend to lean Democratic.

Now, a March date for DACA’s phaseout with hundreds of thousands of young livelihoods on the line is increasing pressure on Orange County Republicans: Royce, Walters, and Reps. Dana Rohrabacher and Darrell Issa.

They all face tough reelection campaigns, and protesters appear regularly outside their offices holding signs about healthcare and the Russia investigation. Depending on how members deal with DACA, immigration could become another galvanizing issue for Democrats there as the 2018 midterms approach.

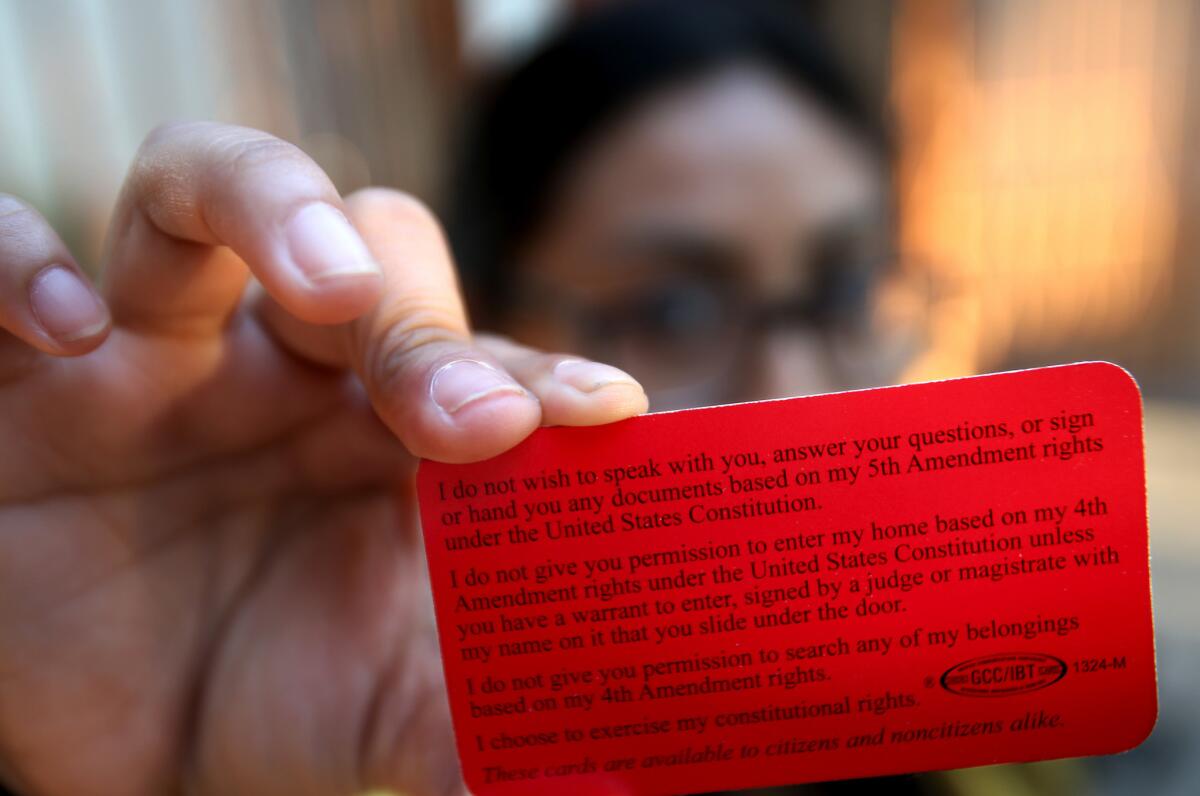

That’s because of people like 23-year-old Lupita, who came to the U.S. illegally as a child and recently led a few dozen students on a march through the small Fullerton College campus. The group chanted, “Undocumented and unafraid,” a slogan coined by the immigrant youth movement a few years ago. Organizers urged them to call Congress members to demand legislation that would eventually grant them citizenship.

“I guess it’s a wake-up call,” said Lupita, who is, despite her chants, afraid of being deported and asked that her full name be withheld.

Lupita also marched a few years ago when she hoped Congress would pass the Dream Act. But after President Obama rolled out DACA in 2012, the people who had protested with her slipped into the comfort of renewing their permits every two years, focusing on school or careers.

“We gave up momentum after DACA. We became complacent,” said Jose Servin, an organizer with Orange County Immigrant Youth United, which has helped organize fundraisers and legal clinics in the weeks since Trump’s decision. “Now that DACA is going down, we’re seeing more unity between DACA recipients, non-DACA recipients, really the entire movement.”

Demonstrations have popped up in Orange County over the last few weeks, including rallies that drew hundreds of people to Royce and Walters’ district offices.

The district that elected Royce in 1992 was then more than 60% white and less than a quarter Latino. Today, Asian Americans and Latinos make up more than 65% of his district, and the portion of white residents has shrunk to 28%.

The share of Republican voters in Walters’ district has dropped 4 percentage points since she was elected to Congress in 2014, but the districts she’s served since the start of her career show how her constituents have changed dramatically.

The percentage of Latino and Asian voters in the state Assembly district Walters was elected to in 2004 was 11%. Registered voters were overwhelmingly Republican. A little over a decade later, Republicans are ahead by just 9 percentage points in her 45th Congressional District, and Latinos and Asians make up more than a quarter of voters there.

Whether those numbers will make the difference for Republicans such as Royce and Walters remains to be seen. Minority voters have not historically registered to vote or turned out at the same rates as white voters, and that effect is magnified in midterm election years.

Plenty of organizations are trying to change that. Latino Victory Project — a nonpartisan group whose leaders have strong Democratic ties — recently commissioned a poll that suggested a large majority of Latino adults are getting fired up over immigration and generally disapprove of Trump and the Republican Party.

The group is one of many that have promised to harness that potential power by turning out minority voters.

“It could prove to be that Donald Trump turns out to be the greatest Latino organizer of all time,” said Latino Victory Project President Cristobal Alex. The group and its political action committee had a total budget of about $6.5 million last year.

Royce’s Democratic challengers have seized on the moment. Sam Jammal, the son of Colombian and Jordanian immigrants, said the congressman’s approach would leave DACA recipients “second-class citizens.” Phil Janowicz, a former professor, called Royce’s shift “blatant hypocrisy from a desperate politician.”

Even among the GOP party faithful, support for hard-line immigration policies appears to have waned. In January, a statewide poll by the Public Policy Institute of California showed that 65% of California Republicans believe immigrants living here illegally should be allowed to stay if they meet certain requirements.

So far, the only California Republicans in Congress who have signed on to DACA replacement legislation are Reps. Jeff Denham and David Valadao, who represent Central Valley districts that are heavily Latino and have long supported immigration reform. Royce and Walters declined to comment further through their representatives.

Even if other vulnerable Republican members do support a DACA replacement, it may not be enough. Both Royce and Walters have mentioned only the need to give DACA recipients residency, not citizenship. Reinvigorated “Dreamers,” many of them too young to have experienced life in the shadows as adults, are demanding a clear path to citizenship in “clean” legislation without the provisions for increased immigration enforcement the White House has proposed. House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi has called those demands — which include funding for a border wall, increased funding for border security and dramatic changes to the country’s legal immigration system — “trash.”

“They don’t want to sell out their parents … by trading a work permit for more deportations or a militarization of the border,” said Rosa Hernandez, a DACA recipient who works for the nonprofit Public Law Center, which has been providing free legal advice to immigrants.

If Congress agrees on anything but a clean bill, members risk backlash from immigrants who reject the idea of DACA recipients like Hernandez being used as bargaining chips for tougher immigration rules.

Hope for a clean bill is what motivated 21-year-old Min Jung Park, a student at UC Irvine, to fly to Washington to join one of her first immigration protests this summer. Park, a DACA recipient who lives in Walters’ district, said she is more worried about what the deal-making could mean for her 15-year-old sister, who is no longer eligible for DACA because of Trump’s decision.

Park, who came to the country when she was 7 and overstayed her visa, said she doesn’t buy Walters’ statements about DACA.

“That’s only going to put more of us [protesting outside her office] because we want her to take a clear side,” she said.

Minerva Gomez, 33, agrees. Gomez isn’t a DACA recipient but left the country voluntarily in 2010 before a family member petitioned for her return. She advocates for immigrant rights as an organizer for faith-based Orange County Congregation Community Organization.

A little more than six weeks ago, she became a citizen and a newly registered voter in Royce’s district.

“People like Royce, who didn’t have a moment to listen to us before, are just going to have to listen,” Gomez said of the 2018 elections. “Because we’re becoming a population that’s not just going to stay silent. We’re going to hold these folks accountable.”

For more on California politics, follow @cmaiduc.

ALSO

Updates on California politics

California sues Trump administration over plan to end DACA

Hard-line White House immigration proposals could derail deal to protect ‘Dreamers’

IN THEIR WORDS: ‘Dreamers’ tell us what the end of DACA would mean for them.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.