Opinion: Can the Church of England’s and Pope Francis’ strides on same-sex marriage help save dying institutions?

- Share via

It was a simple blessing: a giving of thanks for love, friendship and commitment. Yet this prayer, read at a church in Suffolk, east England, on Sunday morning, has become a lightning rod for England’s premier religious institution.

After midnight Saturday, the Church of England — the state church, whose supreme governor is the king — sanctioned same-sex couples to be blessed for the first time in its 489-year history. Backlash to this move, as well as those recently made by other denominations, highlights the urgent challenge now facing these ailing religious institutions: Keep up with the times, or die out completely.

A new document explains a radical change in Vatican policy by insisting that people seeking God’s love and mercy shouldn’t be subject to ‘an exhaustive moral analysis’ to receive it.

Just one day after the new rules over same-sex blessings (which for now can only take place within an existing service) came into force, Pope Francis enacted a similar blueprint for Roman Catholics. On Monday, he approved blessings for same-sex couples — with the caveat that they could go ahead “without any type of ritualisation or offering the impression of a marriage.” Even with that small print, it was a marked change from the Catholic Church’s decree two years ago that prayers for same-sex pairs would remain verboten as “God does not bless sin.”

The pope’s seal of approval should be an unequivocal sign that Christianity is ready to edge into the 21st century. But for the Church of England, senior figures backing the LGBTQ+ cause has so far inflamed tensions.

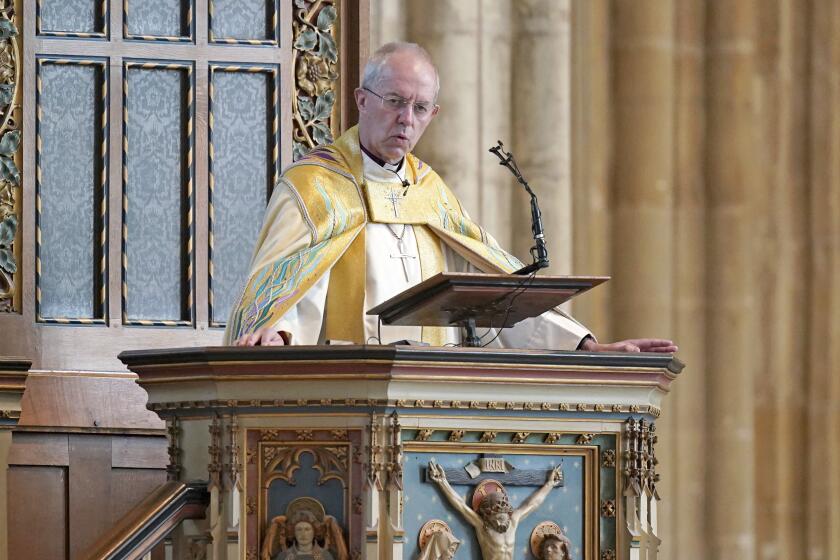

Support for blessing gay couples from Justin Welby and Stephen Cottrell, the archbishops respectively of Canterbury and York (the highest offices within the church), has in recent months led to calls for Welby to resign. Cottrell last month admitted that the matter is “stretching us to breaking point.” After almost a decade of debate, some bishops responded to last week’s rule change announcement by accusing the General Synod, the church’s ruling body, of creating a “tectonic divide” that may never heal. (The American counterpart denomination, the Episcopal Church, is further ahead, having allowed same-sex marriage since 2015.)

It’s all very well for religious conservatives to maintain that doctrine should be observed as it was written millenniums ago. But the church’s failure to address changing social mores is playing out in half-filled pews across the Western world. Between 2013 and 2019, attendance at Sunday services in England dropped by 15%; one report estimated a further 19% fall from 2019 levels, with some churches shutting completely and others being rented out instead.

Thousands of churches in the U.S. were closing for good. To keep our doors open, we had to reinvent the way we use our San Pedro church and property.

Some U.S. congregations are at a similar crossroads. Since the United Methodist Church eased off on enforcing its ban on gay and lesbian ministers and same-sex unions in 2019, a quarter of its around 30,000 U.S. churches will have broken away completely by this year’s Dec. 31 departure approval deadline. Meanwhile, a June Gallup poll reported a decline in church attendance of at least 10% in the U.S. since 2012.

Religious institutions appear to have missed a fundamental truth: In the age of dwindling devotion, the question is no longer what people can offer their church, but what it can offer them. Refusals to accept gay marriage — support for which remains at an all-time high in the U.S. — only highlight how out of step with society the traditionalists have become.

Although there is no denying that hard-liners might be alienated by change — and that fear of it can be powerful — it’s wrong for aging institutions (which, between the church and the monarchy, England has its share of) to assume their worshipers can’t adapt.

The Church of England has formally apologized for its treatment of LGBTQ people but continues to ban same-sex couples from marrying in its churches.

As I looked around at the small, primarily white-haired congregation in Suffolk, who after the service clutched celebratory glasses of fizz to toast the newly blessed couple, it was hard to understand the church’s apparent panic. One 99-year-old congregant praised the couple, two female vicars, for breathing new life into the church. Others attended after news of the service made headlines (one told me she was considering joining the congregation as a result). The vast majority was simply there to worship quietly, without inquiring into the personal lives of others, as they had done for decades.

The concern going forward is that these same-sex blessings are not the peace offering that some churches appear to think; straddling the fence may win them no friends. Campaigners lament that same-sex couples are still denied the rights of heterosexual believers — a matter the Church of England has said won’t progress before 2025. Kicking the can down the road is unlikely to help their cause, either.

Rather than debating the minutiae of religious dogma, the church (along with many other denominations) must choose between embracing our age, or going on living like it’s 1534. If they pick the latter, emptying churches around the world suggest their chance of surviving another 489 years is very slim indeed.

Charlotte Lytton is a journalist based in London.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.