Opinion: Orange County doesn’t want a needle exchange program. But it needs one

- Share via

Opioid overdose deaths in Orange County are rising sharply, with annual deaths nearly tripling in the four years ending in 2021. It is no coincidence that for much of that time, and again today, Orange County is the most populous county in the country without a needle exchange program.

The program that local officials shut down last year, the Harm Reduction Institute in Santa Ana, applied to the state in January for permission to reopen as a home-delivery syringe service program. The city said in May that it “vehemently objects” to the application, citing general public health concerns.

Oregon is the first state to eliminate simple drug possession as a crime and to adopt the policy that drug treatment should be voluntary.

The public’s understanding of syringe service programs, and addiction itself, dangerously lags behind the science, often with fatal results. Research in public health and harm reduction has long shown that these programs are necessary for an effective response to the opioid epidemic and related HIV and hepatitis C transmission risks.

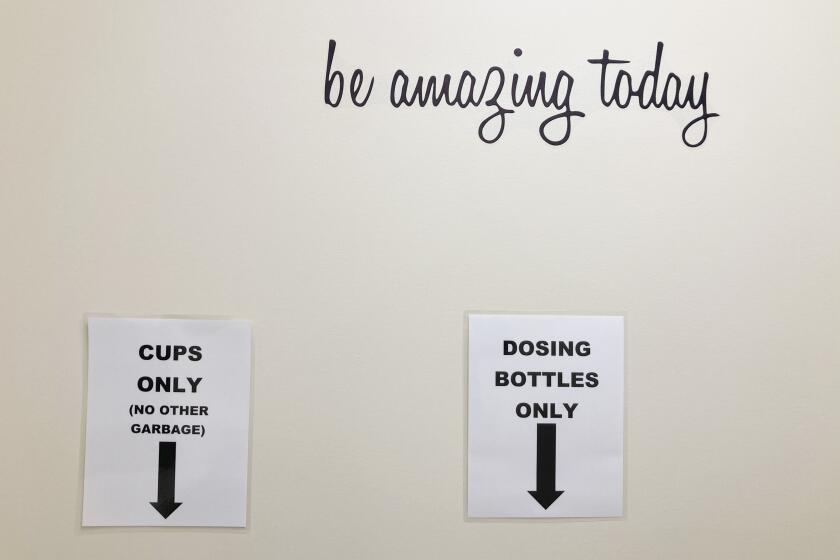

These healthcare providers are often called needle exchanges but really do so much more. They prevent overdose deaths by supplying fentanyl test strips, overdose recognition education, overdose reversal medicine, and access to opioid addiction medicine. In addition, they provide HIV, hepatitis and COVID-19 testing, access to sterile syringes, disposal of used syringes, and connections to medical providers and counseling.

The FDA just made access to Narcan easier to stop overdose deaths. Methadone also should be made more widely available to treat addiction.

In an age of surging fentanyl overdoses, which killed more people in 2021 than guns and cars wrecks combined, the services at these centers save lives and protect communities. And yet elected officials in Orange County have opposed these programs despite a spiking body count and decades of medical research that show they are safe and save lives. Studies indicate nearly every measure of health worsens when these programs are not available to people who use drugs.

Despite the endorsement of syringe service programs by the American Medical Assn., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse, local residents and elected officials often oppose these programs because of misconceptions about these health services and stigma against the people being served.

Republicans want Newsom to veto the ‘drug den’ bill. What they are asking is for California to turn its back on people dying from preventable overdoses.

In 2018, such opposition shut down Orange County’s only needle exchange. The Harm Reduction Institute emerged as a successor but faced similar resistance and was forced to close in January 2022.

At a public hearing in September 2020, Santa Ana’s city attorney had suggested that after banning needle exchanges, the city could make the operation of medical offices or pharmacies that distribute syringes a zoning issue. She said the city could take other enforcement action against them, including “making sure they do have the proper licenses.” Two weeks later, the city started issuing zoning violations against the medical office where the Harm Reduction Institute operated.

Now that the institute is trying again to serve patients, the city will face some legal hurdles if it continues trying to block care.

One diagnosis can eclipse another, leading to a skewed approach. Integrating care and cross-training professionals shows promise.

Drug addiction is a disability protected by the Americans With Disabilities Act and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. Public entities, such as local governments, jails and hospitals, therefore cannot deny health services or services provided in connection with drug rehabilitation to people who use illegal drugs and are otherwise entitled to such services. This means that unless there is objective evidence that a program and its clients pose a risk of direct harm to others (not themselves), federal civil rights laws protect these healthcare providers and their patients from discriminatory zoning and safety rules. Courts are clear that generalizations about public safety risks will not suffice.

Illicit fentanyl is a scourge. It has poisoned the street drug supply and killed thousands of unwitting people.

Ensuring that people with drug addictions receive the health services they are entitled to under the nation’s civil rights laws is a top priority of the Department of Justice. Likewise, one of the key objectives in the White House’s 2022 National Drug Control Strategy is to increase the number of syringe programs across the country, especially in counties with none.

Orange County’s elected leaders should listen to the medical experts and not place stigma and stereotypes over science. They should support opening syringe programs, and when residents object, they should defend the programs’ right to exist. Doing so will save lives and protect neighborhoods — and it’s the law.

David Howard Sinkman is a senior associate at the O’Neill Institute at Georgetown University Law Center. He served as a federal prosecutor in the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Louisiana, where he was the office’s opioid coordinator and civil rights coordinator. Ricky Bluthenthal is a professor of population and public health sciences and the associate dean for social justice in the Keck School of Medicine at USC. He co-founded the Oakland syringe service program in the 1990s.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.