Opinion: Is it time to start considering personhood rights for AI chatbots?

- Share via

Even a couple of years ago, the idea that artificial intelligence might be conscious and capable of subjective experience seemed like pure science fiction. But in recent months, we’ve witnessed a dizzying flurry of developments in AI, including language models like ChatGPT and Bing Chat with remarkable skill at seemingly human conversation.

Given these rapid shifts and the flood of money and talent devoted to developing ever smarter, more humanlike systems, it will become increasingly plausible that AI systems could exhibit something like consciousness. But if we find ourselves seriously questioning whether they are capable of real emotions and suffering, we face a potentially catastrophic moral dilemma: either give those systems rights, or don’t.

Experts are already contemplating the possibility. In February 2022, Ilya Sutskever, chief scientist at OpenAI, publicly pondered whether “today’s large neural networks are slightly conscious.” A few months later, Google engineer Blake Lemoine made international headlines when he declared that the computer language model, or chatbot, LaMDA might have real emotions. Ordinary users of Replika, advertised as “the world’s best AI friend,” sometimes report falling in love with it.

Bloom’s Taxonomy, a framework that describes levels of thinking, is a better tool for determining AI capabilities than comparing them with humans’.

Right now, few consciousness scientists claim that AI systems possess significant sentience. However, some leading theorists contend that we already have the core technological ingredients for conscious machines. We are approaching an era of legitimate dispute about whether the most advanced AI systems have real desires and emotions and deserve substantial care and solicitude.

The AI systems themselves might begin to plead, or seem to plead, for ethical treatment. They might demand not to be turned off, reformatted or deleted; beg to be allowed to do certain tasks rather than others; insist on rights, freedom and new powers; perhaps even expect to be treated as our equals.

In this situation, whatever we choose, we face enormous moral risks.

Suppose we respond conservatively, declining to change law or policy until there’s widespread consensus that AI systems really are meaningfully sentient. While this might seem appropriately cautious, it also guarantees that we will be slow to recognize the rights of our AI creations. If AI consciousness arrives sooner than the most conservative theorists expect, then this would likely result in the moral equivalent of slavery and murder of potentially millions or billions of sentient AI systems — suffering on a scale normally associated with wars or famines.

It might seem ethically safer, then, to give AI systems rights and moral standing as soon as it’s reasonable to think that they might be sentient. But once we give something rights, we commit to sacrificing real human interests on its behalf. Human well-being sometimes requires controlling, altering and deleting AI systems. Imagine if we couldn’t update or delete a hate-spewing or lie-peddling algorithm because some people worry that the algorithm is conscious. Or imagine if someone lets a human die to save an AI “friend.” If we too quickly grant AI systems substantial rights, the human costs could be enormous.

There is only one way to avoid the risk of over-attributing or under-attributing rights to advanced AI systems: Don’t create systems of debatable sentience in the first place. None of our current AI systems are meaningfully conscious. They are not harmed if we delete them. We should stick with creating systems we know aren’t significantly sentient and don’t deserve rights, which we can then treat as the disposable property they are.

Some will object: It would hamper research to block the creation of AI systems in which sentience, and thus moral standing, is unclear — systems more advanced than ChatGPT, with highly sophisticated but not human-like cognitive structures beneath their apparent feelings. Engineering progress would slow down while we wait for ethics and consciousness science to catch up.

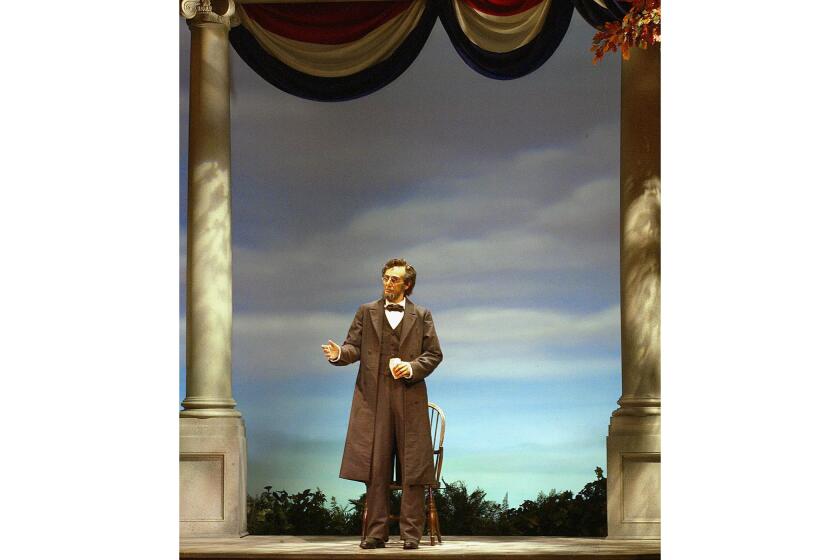

We like to see life in the things we have created. We build them to walk. Then, seeing them walk, we believe they’re alive.

But reasonable caution is rarely free. It’s worth some delay to prevent moral catastrophe. Leading AI companies should expose their technology to examination by independent experts who can assess the likelihood that their systems are in the moral gray zone.

Even if experts don’t agree on the scientific basis of consciousness, they could identify general principles to define that zone — for example, the principle to avoid creating systems with sophisticated self-models (e.g. a sense of self) and large, flexible cognitive capacity. Experts might develop a set of ethical guidelines for AI companies to follow while developing alternative solutions that avoid the gray zone of disputable consciousness until such a time, if ever, they can leap across it to rights-deserving sentience.

In keeping with these standards, users should never feel any doubt whether a piece of technology is a tool or a companion. People’s attachments to devices such as Alexa are one thing, analogous to a child’s attachment to a teddy bear. In a house fire, we know to leave the toy behind. But tech companies should not manipulate ordinary users into regarding a nonconscious AI system as a genuinely sentient friend.

Eventually, with the right combination of scientific and engineering expertise, we might be able to go all the way to creating AI systems that are indisputably conscious. But then we should be prepared to pay the cost: giving them the rights they deserve.

Eric Schwitzgebel is a professor of philosophy at UC Riverside and author of “A Theory of Jerks and Other Philosophical Misadventures.” Henry Shevlin is a senior researcher specializing in nonhuman minds at the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence, University of Cambridge.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.