Op-Ed: Forty years ago Vincent Chin was killed. My mother passed along her grief, and a lesson about America

- Share via

Every few months I think of Vincent Chin. This Thursday marks 40 years since his death after he was brutally attacked by two white men with a baseball bat in Detroit. Chin was out with friends at his bachelor party that night. His killers were autoworkers, and they allegedly believed the rise of Japanese auto sales in the U.S. was behind the job losses in their industry.

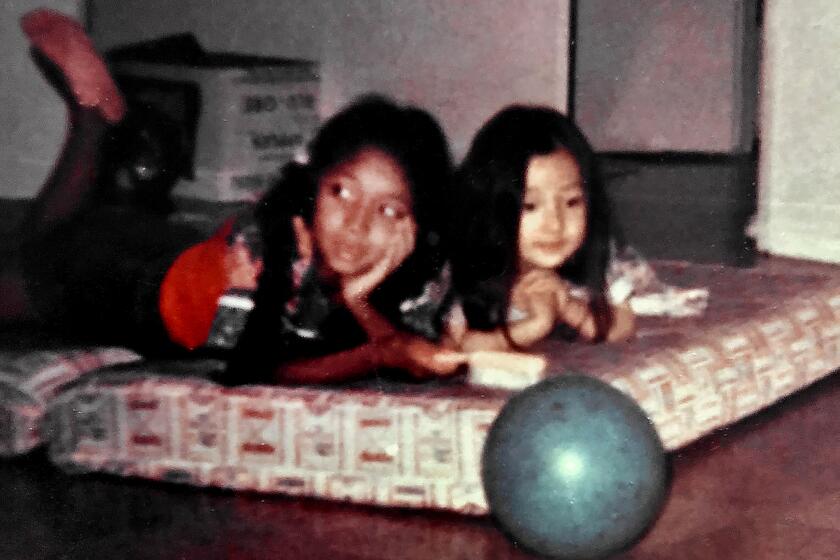

I was only 10 years old at the time. I remember being with my mother at our family fast-food store, a fish and chips shop in a Southern California strip mall, standing behind the fake wood laminate counter. It was afternoon. Ma had just finished reading the Chinese language newspaper, Shi Jie Ri Bao, which was unusual. She never read the newspaper at work. But Mom made an exception that day, when the front-page story was about a man named Vincent Chin.

Ma told me that Vincent was beaten by two men. That he didn’t die right away. That after he spent four days in a coma on life support his mother consented to removing the tube that was keeping him alive. That after the machine that was breathing for him was turned off, Vincent died.

The Atlanta shootings and other attacks against Asian Americans have spurred some to have difficult conversations with their elders.

I remember the afternoon light shining through the glass walls of the shop. It was Saturday, and like most Saturdays of my childhood, I was there to work, an extra pair of hands. Even though I spent all day around my mother on these Saturdays, she didn’t like to talk much at the store. That day she wanted to tell me about Vincent Chin.

I remember her telling me about a chase, an empty parking lot, a baseball bat. I don’t say anything. I know if I keep quiet, Ma will keep talking.

They thought he was Japanese. He wasn’t Japanese, he was Chinese! Americans don’t like Asians, especially Americans in Detroit, where Vincent Chin died. The men who beat him up — they blamed the Japanese, because people are buying Japanese cars instead of American cars. His killers didn’t even get jail time. But he wasn’t Japanese, he was Chinese!

At that age, I still interpreted the world through my mother. She was telling me America is not so welcoming. She was telling me America is not so great after all.

But I didn’t need her to tell me that. We had immigrated to the country from Taiwan five years before, when I was a kindergartener. Our first store, Dino’s, was vandalized six times in the span of six months. I was bullied every day at school, until one day, in a fit of rage and helplessness, I landed a punch on my 5-year-old tormentor.

That Saturday, when my mother told me about Vincent Chin, she was imparting her grief to me. I accepted it wordlessly, and like many other children of immigrants, I held onto it for safekeeping, until it became my own.

Now, every year toward the end of June, a veil of sadness descends. Vincent Chin was to be married on June 28. Instead, he was buried on the 29th.

I’ve come to associate some words and objects that shouldn’t be about Vincent with him. Like many kids who grew up in L.A., I am a Dodgers fan, but sometimes I see a baseball bat and shudder. Words such as “only child” make me think of him, the only child of Lily and Bing Hing “David” Chin. And sometimes, when I hear the words “it’s not fair,” I think of how those were the last words he uttered. It’s not fair.

The fallout from the L.A. riots 30 years ago had a splintering effect on my Korean-Black family and on my cousin and me. Our relationship never healed.

For years Vincent’s mother, Lily Chin, sought justice for her son, but his killers never served any jail time. Their second-degree murder charges were reduced when they agreed to plead guilty to manslaughter, for which they were sentenced to probation and a fine. In 1987, Lily Chin left America and went back to China. I think of how she came to America in the 1940s as a new bride, full of hope. She left alone.

A few months ago, I asked my mother whether she remembers telling me about Vincent Chin.

Who?

I didn’t know how to say Vincent’s name in Chinese.

In 1982, the Chinese guy who was beaten to death in Detroit by two white men.

Blank stare. There was no hint of recognition in her face.

Ma, you remember, the guy was supposed to get married. He was killed by two autoworkers a week before his wedding. His killers never got jail time.

Ma shakes her head, her lips press together tightly.

I don’t remember.

OK, Ma.

My mother’s memory is fading. I think about how all those years before, she gave me her grief for safekeeping.

All the more reason for me to never forget.

Jane Kuo is the author of “In the Beautiful Country.” @janekuowrites

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.