Op-Ed: How COVID created a universal midlife crisis

- Share via

The post-pandemic horizon is coming into focus. Even with the rise of new Omicron subvariants nipping at our heels, fear is being replaced with cautious optimism. But we aren’t going back to pre-pandemic normal. In fact, many people during the past two COVID-19 years chose to fundamentally alter their pre-pandemic path. More than 30 million U.S. workers quit their jobs in the second half of 2021, the equivalent of the entire population of Texas.

Virtually everyone at every level of the workforce was forced by the pandemic to reconsider where they work. Nearly a third of U.S. workers younger than 40 reported that they’ve thought about changing their occupation since the start of the pandemic. And it’s affected blue-collar and white-collar industries alike.

But when researchers pull back the layers, the emerging picture is that there is more to the “Great Resignation” than just dissatisfaction with salary. Many who left their jobs were looking for more respect and meaning, a trend that continues. These are the elements of what psychologists commonly recognize as contributing to a “midlife crisis.” The Great Resignation, it turns out, is really the Great Midlife Crisis.

The pandemic disruption is crystallizing priorities for employees and employers alike.

By disrupting our lives and placing us in a deeply unfamiliar world, while also confronting our own mortality, COVID-19 created a universal turning point. Indeed, this is a standard characteristic of the identity crisis typically associated with middle age. As older age comes into view, people begin to question their identity (who am I?) and their trajectory (where am I going?). The pandemic created conditions for a similar type of identity crisis for people of all ages.

Three lines of research we have conducted over the past two decades offer insights into what drove the Great Resignation and what employers might learn from this period.

First, the pandemic made people keenly aware of their own mortality, with more than 6 million deaths worldwide. When people think about the possibility of their own death, it gives them a broader perspective on their life and leads them to consider their legacy. For example, in one study in which we had people think about an existential crisis like global warming, they were more likely to express a desire to create an enduring positive legacy.

Second, the pandemic activated what psychologists call counterfactual thinking, or “if-only” thoughts. These thoughts of “what might have been” are triggered by breaks in routines as people consider alternative realities. For example, getting into an accident after taking a different route home from work initiates if-only thinking (“If only I had taken my usual route, this wouldn’t have happened!”). Counterfactual reflections are often triggered by rare episodes in which rapid, intense and clear change occurs, e.g., a novel pandemic.

Counterfactual thinking helps people connect the dots of their lives. It can bring meaning — or its absence — into sharp focus. And finding meaning is how people can transform something traumatic into the seeds of growth. The pandemic as a turning point has led many people to reflect on where they were two years ago, where they are today and where they are heading.

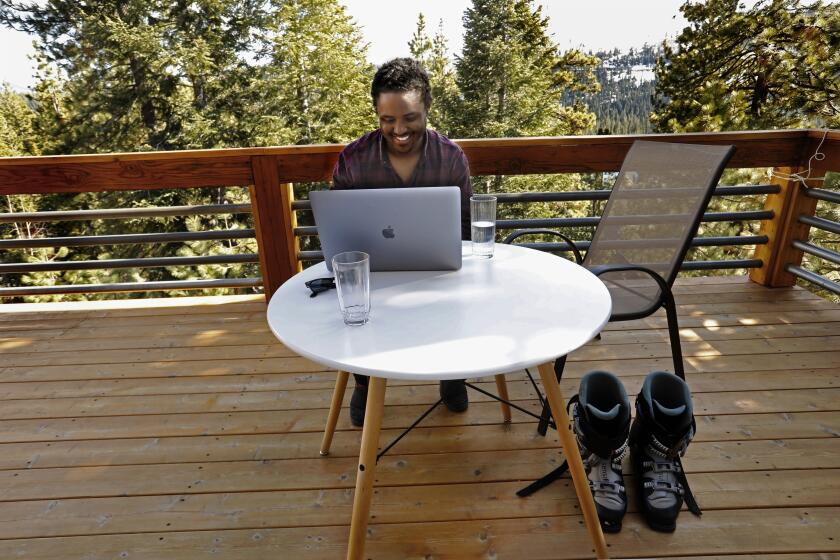

Finally, the dramatic changes created by the pandemic have altered people’s contexts and routines, and therefore their perspectives. People who had maintained the long grind of commuting to the office suddenly stopped commuting altogether and began working from a new location (the home). This instantaneous shift in workplace — where many people spent 35 to 55 hours per week — can be similar to spending time in a foreign land.

Younger workers are quitting jobs at record rates and demanding changes to the workplace that will benefit all of us.

Our research shows that foreign experiences can give people greater clarity about who they really are. We found that people who have lived abroad are more likely to agree with the statement “I have a clear sense of who I am and what I am” than people planning to go abroad in the future. These experiences create self-clarity because they promote a counterfactual mindset that helps people recognize which behaviors are a product of their environment rather than being inherent in themselves. The pandemic-induced shift in setting and routine has similarly led many people to appreciate what truly defines them, versus what was being driven by their daily surroundings.

The combination of mortality salience, counterfactual reflection and foreign experiences — like the proverbial midlife crisis — has led people to consider where they are headed and where they want to go.

For many, that meant saying, “I quit.” It’s not surprising then that a toxic work culture is a stronger predictor of resignations during the pandemic than a desire for higher compensation. That is likely to stay true for workers even as the pandemic recedes.

The organizations that are going to win the post-pandemic contest for workers will be the ones that can demonstrate they have emerged from the pandemic with positive changes to their work cultures. Lifting employees out of their pandemic midlife crises will require the promise — or at least the likelihood — that their jobs can offer a more meaningful path ahead.

Adam Galinsky is a professor at Columbia Business School. He is the co-author of “Friend & Foe.” Laura Kray is a professor at the Haas School of Business at UC Berkeley and faculty director of the school’s Center for Equity, Gender and Leadership.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.