Op-Ed: We’re losing the fight against superbugs, but there’s still hope

- Share via

As parents, we inherently want to protect our children. We tell them stories with happy endings and reassure them that there aren’t monsters hiding under the bed.

But there’s an enemy living among us that poses a fatal threat to kids and adults alike — and we’re simply not doing enough to stop it.

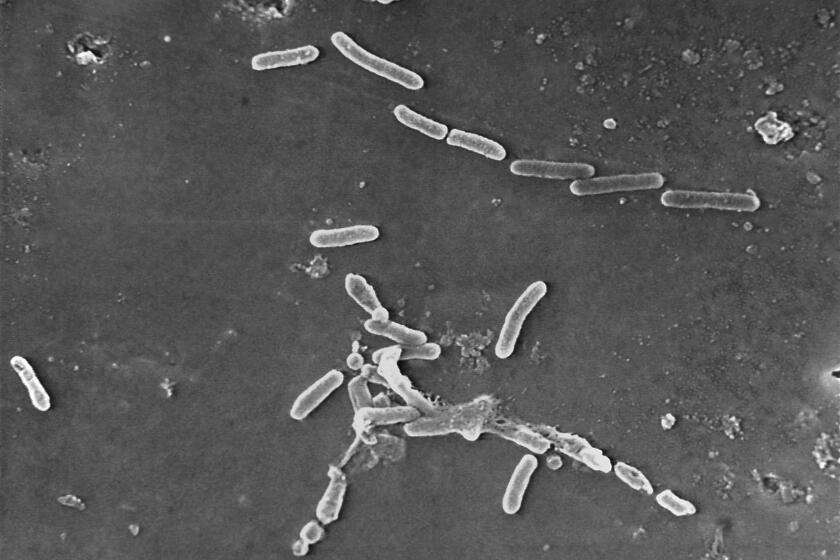

These enemies are “superbugs” — bacteria and fungi that are resistant to antibiotics and other medications. All microbes, from everyday bacteria to killer superbugs, are constantly evolving. And paradoxically, exposing microbes to antimicrobials — whether a common antibiotic for strep throat or a potent antifungal treatment given in the hospital — can make them stronger in the long run.

While most of the microbes die when treated, the ones that survive can reproduce. These new generations of microbes can build up resistance to certain antimicrobials, rendering some medications less effective or ineffective over time.

Unfortunately, this natural evolutionary process is speeding up for several reasons. We greatly overuse antibiotics in patients with viruses, like the flu, common colds and bronchitis — without benefit. And modern medical care has increased the demand for antibiotics. Advances in cancer care, organ transplants and surgeries such as hip and knee replacements have become much more common. These procedures can extend and improve life, but patients often require antimicrobials because they are at high risk of developing infections.

‘Superbugs’ have joined the ranks of the world’s leading infectious disease killers.

Bacteria are mutating at a speed that outpaces the development of antibiotics. Penicillin was discovered in 1941, but it wasn’t until 1967 that penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumococcus was first identified. By contrast, consider an antibiotic for multidrug-resistant bacteria released in 2015, called ceftazidime-avibactam. That same year a strain of bacteria emerged that was resistant to this new antibiotic.

Drug-resistant pathogens are one of the greatest healthcare threats of our time — for everyone, everywhere, including adults and children. More than 1.2 million people died worldwide from antibiotic-resistant infections in 2019 alone. Multidrug-resistant infections are on the rise in kids. More of these infections originate outside of our hospitals and within our communities.

Without effective antibiotics, run-of-the-mill pneumonia or skin infections can become life-threatening.

COVID-19 exacerbated the situation. Amid the widespread uncertainty and limited treatment options at the beginning of the pandemic, doctors often used antibiotics to treat COVID-19 patients as they tried to help them. Patients may also have been given antibiotics in instances in which it was difficult to distinguish between bacterial pneumonia, which requires antibiotics, and COVID-19.

Hospital stewardship programs — which manage the careful and optimal use of antimicrobial treatments — also had to redirect their limited resources away from antibiotic use to focus on the complex administration of COVID-19 therapeutics. And severely ill patients on ventilators were at a higher risk of contracting secondary infections, especially while their immune system was weakened.

These factors led to an increase in drug-resistant infections acquired in hospitals during the pandemic. Drug-resistant staph infections, MRSA, jumped 34% for hospitalized patients in the last quarter of 2020 compared with the same period in 2019.

Unless scientists invent new antibiotics, superbugs will kill 10 million people annually by 2050.

Proportionately, those numbers have the biggest impact on California, which has the most coronavirus cases of any state. Los Angeles, San Diego, Riverside, Orange, San Bernardino, and Santa Clara counties have the highest number of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the state.

Prior to COVID-19, we made initial progress in the fight against antimicrobial resistance. In 2014, California was the first state to pass a law requiring antimicrobial stewardship programs in hospitals. In 2019, Medicare began requiring antibiotic stewardship programs.

Some modest federal investments have also been made in antimicrobial research and development, but not enough to generate the pipeline patients need. We must increase support for antimicrobial stewardship practices, which were under-resourced even before the pandemic. Teaching practitioners to safely use and monitor antimicrobial treatments is a significant step.

We also need to develop novel antimicrobial medicines capable of defeating the superbugs that have grown resistant to previous generations of treatments. But market incentives are misaligned. Because doctors prudently limit their use of antimicrobials to avoid further resistance, there isn’t high demand to sustain the development of new products, which take years of research and billions of dollars in investments.

As a result, many large biopharmaceutical companies have stopped antimicrobial research entirely. And many smaller startups have had success at first, only to face bankruptcy. That’s part of the reason why there have been few new classes of antibiotics developed in the last 35 years.

This is a textbook case of a market failure, but government intervention can help realign market incentives.

The PASTEUR Act is a bipartisan bill in Congress that would establish a payment model for critically needed antimicrobials.

Currently, the government pays manufacturers based on the volume of drugs sold. But under PASTEUR, the government would enter into contracts with manufacturers and pay a predetermined amount for access to their novel antimicrobials — allowing scientists to innovate new treatments without fear of an insufficient return on investment due to low sales volumes.

Essentially, the bill would switch the government from a “pay-per-use” model for antimicrobials to a subscription-style model that pays for the value antimicrobials bring to society. By delinking payments to antimicrobial makers from sales volumes, the measure would stimulate investment in new antibiotics.

The bill would also provide resources to strengthen hospital antimicrobial stewardship programs, which help clinicians use antimicrobials prudently and help the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention closely monitor resistance. Hospitals should join public health leaders in supporting this legislation and invest more of their resources in their antimicrobial stewardship programs.

Unfortunately, superbugs aren’t an easy enemy to defeat. We need to be fighting them more vigorously to ensure that they don’t get around our best defenses.

Annabelle de St. Maurice is an associate professor of pediatric infectious diseases at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, and head of pediatric infection control and co-chief infection prevention officer at UCLA Health.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.