Op-Ed: Why my daughter hates (whitewashed) AP history

- Share via

My daughter hates her AP U.S. history class. She hates studying for the Advanced Placement exams in early May. That’s not because she’s a bad student. It’s because she’s a good student. She just read a book about the War of the Roses on her own time; James Baldwin, who has a lot to say about America’s racist history, is one of her favorite writers. As a result, she recognizes bland, boring boosterish bilge when it is dumped on her.

With all the fuss Republicans have been making about the need for more patriotism in the classroom, you might believe that U.S. high school history courses today are bastions of antiracism that dwell only on America’s flaws. But unfortunately, my daughter’s history course is as white, and as whitewashed, as Donald Trump could ever hope.

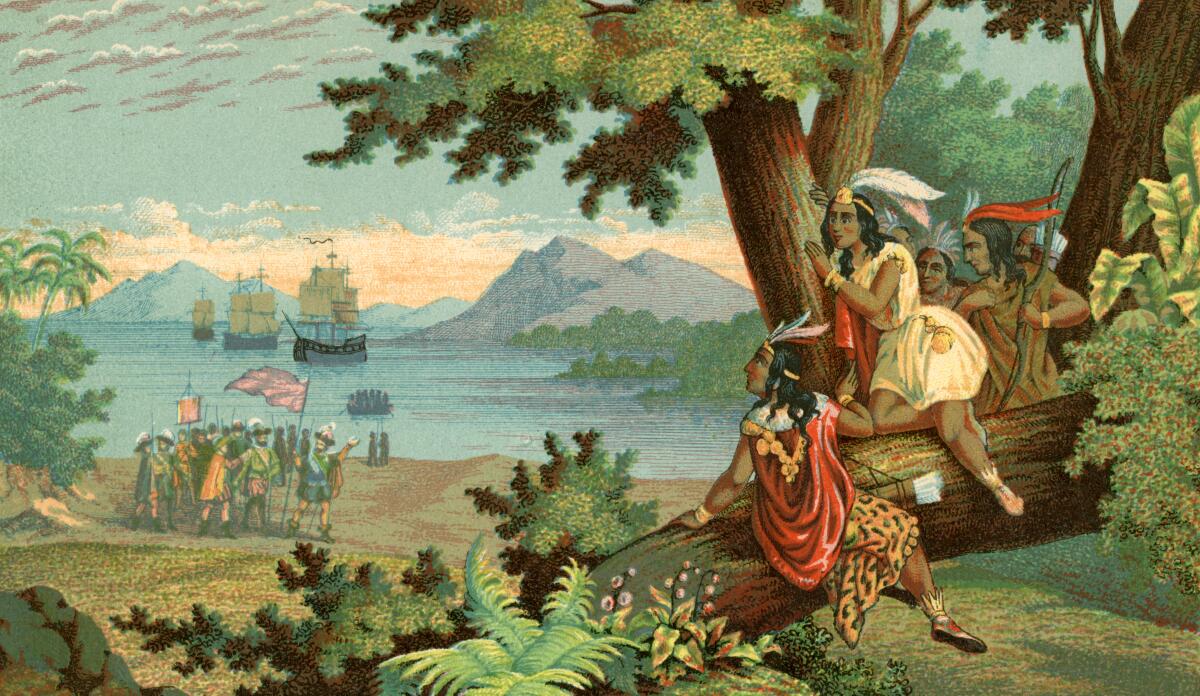

When I was in high school my AP history course was based on Thomas Bailey’s “The American Pageant,” a doorstopper originally written in the 1950s whose purple prose seemed calculated to distract from the vast swaths of the U.S. story it ignored or obscured. Bailey did not teach me, for example, that Christopher Columbus cut off the hands of Hispaniola’s Taino people when they did not bring him enough gold.

That was 30 years ago. I hoped that my daughter’s distance-learning high school course, administered through a leading university, would be better.

My heart sank when I found out she was reading “The American Pageant,” now with new writers and in its 17th edition (though my daughter used the 16th). It’s still a doorstopper and, my daughter informs me, still teaching Black history, Indigenous history, labor history and a lot more very, very badly.

In February, CBS News asked Ibram X. Kendi to review four U.S. history textbooks, including “The American Pageant.” For starters, Kendi pointed out “Pageant’s” unabashed use of “mulatto,” from a root word meaning “mule” and considered a slur regarding biracial people. The textbook also refers to enslaved Africans in America in 1775 as “immigrants.”

The soft-pedaling of Columbus’ genocidal treatment of the Taino people hasn’t changed: “Enslavement and armed aggression took their toll , but the deadliest killers were microbes, not muskets,” “Pageant” assures the reader blithely.

“Throughout pretty much the entire book, Indigenous populations aren’t much more than an afterthought,” my daughter says.

Nor is there much discussion of how Black people freed themselves by abandoning Confederate plantations and fleeing behind Union lines. Instead, according to the textbook, “blacks found themselves emancipated and then re-enslaved” by Union troop movements, as if they had no agency themselves. It also emphasizes that some “initially responded to news of their emancipation with suspicion and uncertainty.”

“‘Pageant,’” my daughter says, “very much takes the view that the Emancipation Proclamation caused the slaves to rise up rather than the other way around.”

In line with discredited racist Jim Crow-era historiography, the textbook also emphasizes that John Brown, who dedicated his life to trying to free enslaved people, was “probably of unsound mind”; his attack on Harper’s Ferry is described as a “crackbrained scheme.” In contrast, Daniel Webster and Henry Clay, who temporized and waffled on the morality of slavery, are celebrated.

“The book just loves this idea of compromise,” says my daughter. “It champions these men who thought the correct response to slavery was ‘only some states should have slaves.’ ”

School texts have long glorified the status quo and encouraged blind patriotism and obedience to authority. James W. Loewen’s book “Lies My Teacher Told Me” examined a range of popular history textbooks including “The American Pageant” in 1995. He concluded that most of them apologized for racism, ignored poor people and women and presented the past in a way that “renders many Americans incapable of thinking about our present and future.”

Teaching history this way, as Loewen noted, causes students to tune out. My daughter’s AP history course is very test-focused. The emphasis is on getting students to regurgitate facts and interpretations, not grappling with gray areas, or connecting then and now.

Because she cares about the world, my daughter would be interested in a rundown on American imperialism that isn’t an apologia. Because she is trans, she deserves to know how the current deluge of anti-trans laws in state legislatures is connected to a U.S. legacy of homophobia. But her AP history class isn’t much interested in such issues.

In fact, my daughter’s course dead-ended in the 1990s, so the last 20 years — 9/11, the Iraq war, Obamacare, Trump — weren’t discussed. Are textbooks and teachers deliberately trying to strip the past of relevance?

The answer has to be yes. “Relevance” is another way of saying “controversial.” Teaching history in the context of current political events is likely to generate strong opinions from students, and worse, from their parents. So is teaching about queer history, or Black history, or colonialism from the perspective of the colonized. So is teaching about Columbus cutting off people’s hands.

Any honest retelling of American history will make us question many of this country’s choices. But those in power, whether textbook authors, school districts or politicians, don’t want to be questioned. My daughter’s AP history class is less about informing her than it is about keeping her ignorant and docile. In that it has failed. But, as retribution, it has bored her unrelentingly for a solid year.

Noah Berlatsky is a freelance writer in Chicago.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.