Op-Ed: How the Los Angeles Times shilled for the racist eugenics movement

- Share via

Last month, Caltech announced that the names of six men with historical ties to the university would be removed from all “campus buildings, assets, and honors.” This unnaming came as the institution renounced its historical connections to the Human Betterment Foundation, a zealous pro-eugenics organization that influenced and admired Nazi racial hygiene policies in the 1930s and 1940s. Caltech determined that prominent trustees of the foundation, such as Caltech’s inaugural president and Nobel laureate Robert A. Millikan, no longer deserved to be commemorated at the university.

Also among the six whose names will be scrubbed from Caltech was Harry Chandler, who served as publisher of the Los Angeles Times from 1917 until his death in 1944.

Caltech was correct to recognize the pivotal role of the Human Betterment Foundation in spreading the eugenics gospel. The brainchild of wealthy agribusinessman Ezra Gosney, the foundation — through its biased studies, cherry-picked data collection, propagandizing and political sway — was instrumental in making California the most aggressive sterilizer of any of the 32 U.S. states that passed eugenic sterilization laws. From 1909 to 1979 the Golden State performed compulsory sterilizations on more than 20,000 people deemed “unfit” to have children.

But a largely forgotten chapter of this story of reproductive injustice and discrimination in California is the major role played by Chandler and The Times in popularizing eugenics and championing sterilization as the solution to perceived social problems such as crime and poverty. Chandler was a foundation trustee and, by all accounts, a vocal eugenics advocate. For decades, he lent his stature and the imprimatur of The Times to the cause of these unabashed bigots.

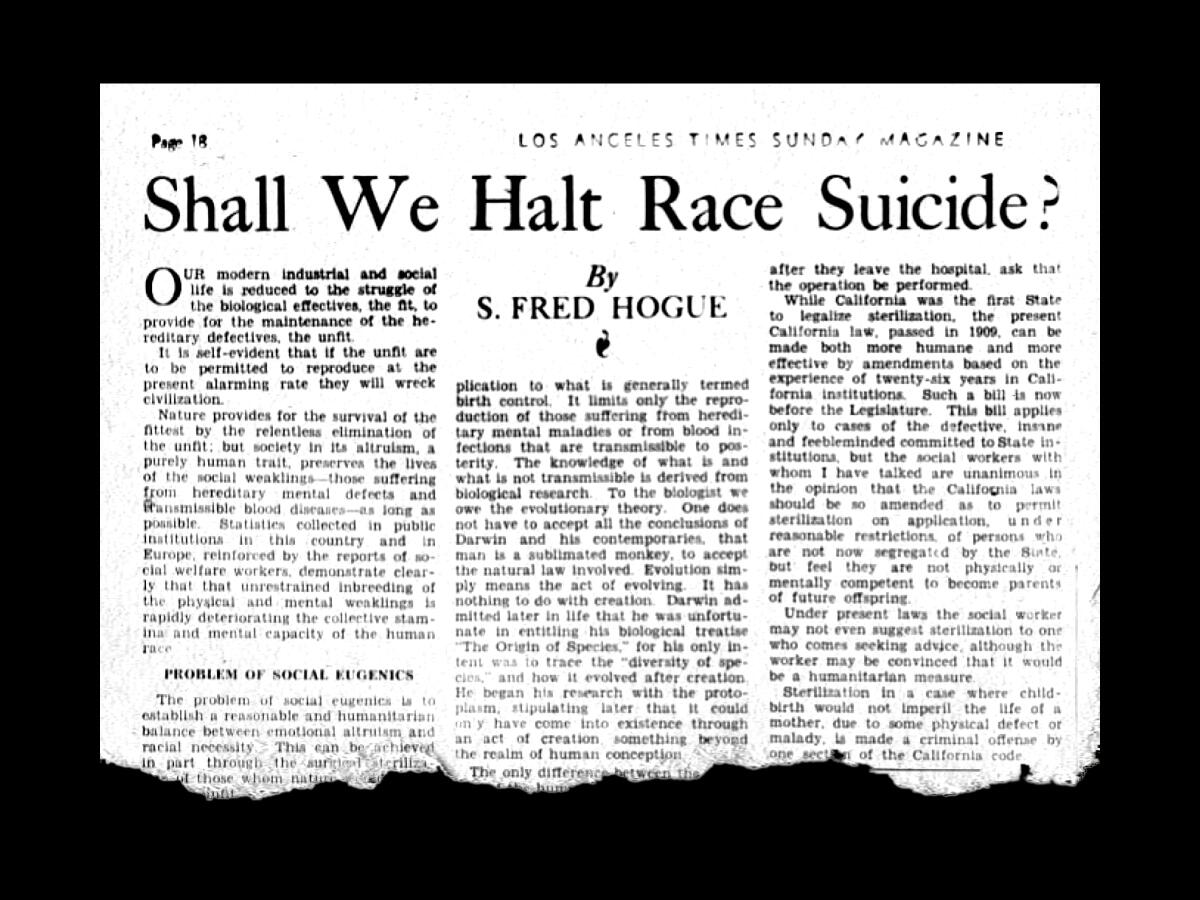

For over six years, from 1935 to 1941, The Times ran a weekly column, “Social Eugenics,” by veteran reporter Fred Hogue. Announced in a lengthy piece entitled “Shall the Unfit Weaken the Race” in the spring of 1935, Hogue laid out a case for eugenic sterilization and the elimination of “defectives” from California and the nation, such as people deemed to be mentally impaired, insane or chronically poor. For Hogue, the title “Social Eugenics” had a particular meaning, encompassing harsh measures such as sterilization and prenuptial certificates to impede the propagation of the “unfit” as well as positive eugenics to ensure that the “fit” were encouraged to breed and thrive.

Hogue was fixated on the loosely defined idea of “unfit” humans and of “unwanted babies,” who, due to their supposed “hereditary defectiveness,” menaced the biological makeup of the population and drained the state of precious resources of charity and care. For Hogue, the stakes were high: “To prevent this form of race suicide, it is absolutely essential that the unfit shall not be permitted to continue to reproduce their kind.”

“Social Eugenics” ran in the paper through the final period of the Depression, Hitler’s rise to power and the beginning of World War II in Europe. Hogue closely followed events around the world, frequently expressing admiration for Japan, Sweden and Germany, which were implementing policies of sterilization and population management. He was particularly taken with Germany, repeatedly praising its sterilization law, passed in 1933 to eliminate the birth of “offspring with hereditary diseases.” As Hogue wrote in 1939, “Hitler, with the support of the German people is an exponent of sterilization of the unfit among his own people. He seeks large families where the bloodstream is pure, and no children where there is an infected blood stream.” Hogue also liked to remind readers that Germany’s sterilization law was modeled on California’s, which authorized the state’s mental institutions to sterilize people suffering from “mental disease which may have been inherited and is likely to be transmitted to descendants.”

For Hogue, purifying California’s “bloodstream” was urgent and necessary, and he promoted local groups with this professed eugenic mission, including the Human Betterment Foundation, the Southern California Branch of the American Eugenics Society, the Eugenics Society of Northern California, and other local organizations, helping cement California’s extensive eugenic networks. He often acted as the mouthpiece of these organizations, quoting at length from newsletters and lectures extolling the forward-looking thinking of eugenicists.

Make no mistake. Even if Hogue often spoke in vague generalities about “race betterment” and nameless “hereditary defectives,” his vision of California was predicated on white supremacy and cruel ableism. Echoing other eugenicists, he demonized supposedly overly fecund Mexicans and allegedly degenerate Dust Bowl migrants, referred to “Negroes” as less civilized, and beat the drum of xenophobia. For example, Hogue wrote in 1936 that the “greater part of the foreign contribution” to America’s melting pot was “dross.” Five years later, he blamed “migrant hordes” for the “excessively high percentage of delinquents [that] continue to flood the state.”

For Hogue and, by association, The Times, the goal was to “protect” California against a descent into dysgenic oblivion. Again and again, Hogue implored the Legislature to enlarge its already expansive sterilization law beyond the walls of mental institutions, and to authorize social workers and other experts to identify “defectives” in the community who should forfeit their reproductive capacity.

Hogue’s column came to an abrupt end in the summer of 1941, when he died. But his column should not be forgotten. Hogue mainstreamed eugenics by presenting it at once as the scientific panacea for complex social problems and as plain common sense for The Times’ primarily white middle-class readership. By giving Hogue such coveted editorial space, Chandler wedded The Times to eugenics during a period when thousands of Californians — disproportionately Latinx people sent to state institutions — were sterilized against their will.

The Times published an editorial in 2017 acknowledging the paper’s role in extolling the virtues of this “deplorable human rights abuse.”

One way of speaking back to Hogue today, and recognizing those harmed by his — and Harry Chandler’s — relentless support of compulsory sterilization is to encourage the state to pass legislation, proposed again in 2021 for the fourth time, to compensate survivors and ensure that this sordid history does not disappear from public memory.

Alexandra Minna Stern, a professor of American culture and history at the University of Michigan, is the author of “Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.