Op-Ed: The Chicano Moratorium of 1970 still has plenty of lessons for today

- Share via

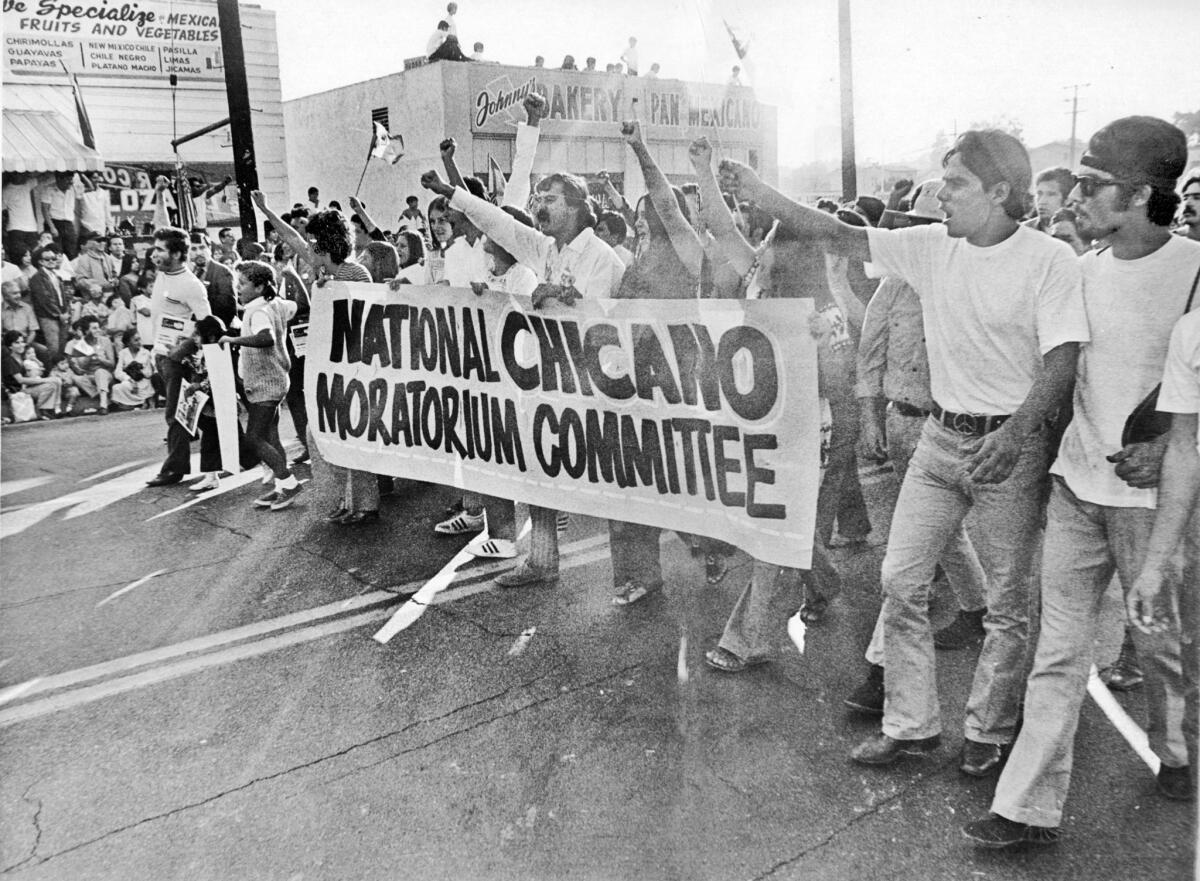

Fifty years ago Saturday, 20,000 people marched through the streets of East Los Angeles to call for an end to the Vietnam War. The Chicano Moratorium Committee, made up mostly of young Mexican Americans under age 30, organized the protest in part to highlight the fact that Latino men were dying in the war far out of proportion to their numbers in the population.

Does that sound familiar? Today, as we battle the coronavirus, Latinos are once again on the front lines and dying in disproportionate numbers. And as we confront that grim fact and try to effect change, there are lessons we can learn from the Chicano Moratorium and the larger movement it was a part of.

The Chicano Moratorium Committee’s vision was rooted in the reality that not only were Mexican Americans and other Latinos dying in Indochina, but conditions back home also needed addressing. Latinos were more likely than non-Hispanic whites to experience poverty, poor housing conditions, substandard education and police brutality. The committee understood that all these things were connected and needed to be addressed holistically. The same is true now.

Today, the moratorium is most often remembered for its tragic ending. After marching down East Los Angeles’ Whittier Boulevard, the protesters gathered for a rally at what was then called Laguna Park. The peaceful event was soon disrupted by Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies, who used the pretext of a crime on Whittier Boulevard to brutally break up the gathering. Deputies with riot gear fired tear gas into the park and beat protesters indiscriminately. The demonstrators, who included many children, ran to adjacent streets, homes and businesses seeking refuge.

Among those who sought shelter was Ruben Salazar, the 42-year-old Los Angeles Times columnist and news director at KMEX, the city’s Spanish-language television station. Salazar ducked into the Silver Dollar cafe to escape the commotion. Outside the bar, Sheriff’s Deputy Thomas Wilson fired a tear-gas projectile into the building, hitting and killing Salazar. He was one of three fatalities that day. Thirty-five-year-old Angel Gilbert Díaz died when his car rammed into a telephone pole as he tried to escape the melee, while Lynn Ward, a 15-year-old, lost his life when an explosion propelled his body through a plate-glass window.

In the aftermath of the Chicano Moratorium and Salazar’s death, organizers shifted the group’s focus, concentrating on the war at home, rather than the one abroad and focusing far more on police brutality, which was a fact of life in poor neighborhoods in Los Angeles. But the tragedy of the moratorium took a toll on the cause. The demonstration that took place on the first anniversary of the event attracted few participants and the Chicano Moratorium Committee disbanded shortly thereafter.

Other Chicano movement groups, including La Raza Unida Party, Las Adelitas de Aztlán, the Centro de Acción Social Autónomo (CASA), and the Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA), took up the mantle of empowering Mexican Americans, but they were unable to organize mass demonstrations on the scale of the moratorium. The numbers would not be surpassed until May 1, 2006, when an estimated 1 million to 2 million people marched through the streets of downtown Los Angeles to protest immigration policies.

Given our situation in 2020, I propose looking back to the Chicano Moratorium to help illuminate these dark times and inspire a new generation of activists. There are plenty of issues to take on: the forced separation of families at the border, the high mortality rate of Latinos and Black Americans due to coronavirus and police brutality. Latinx soldiers are still losing their lives in service to their country at home and abroad. And a primary reason so many Latinos have lost their lives to the coronavirus is that workplace discrimination and lack of access to quality education have relegated many Latinos to essential, but low-paid jobs that put them at high risk.

The Chicano Moratorium organizers understood something essential. The answer wasn’t simply assimilation. These activists celebrated our culture and worried that it was being eroded. They promoted a positive self-image under the banner of Brown Is Beautiful. We strongly need to embrace that sentiment today.

This week, the Republican Party again chose the rabidly anti-Mexican, anti-immigrant Donald Trump as its presidential nominee. He and the party fear what the Chicano Boomers set in motion: the empowerment of Latinos. The GOP has embraced all kinds of policies to limit Latinos’ potential political power with efforts to prevent births on U.S. soil, question citizenship status and undercount Latinos in the U.S. census.

The Aug. 29, 1970, Chicano Moratorium and the tragic events of that day should not simply be venerated. Instead we should use them to reinspire us to look at our situation holistically and to make change in the present in order to forge a more just future.

Ernesto Chávez is a professor of history at the University of Texas at El Paso and the author of “¡Mi Raza Primero! (My People First!): Nationalism, Identity, and Insurgency in the Chicano Movement in Los Angeles, 1966-1978.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.