Op-Ed: My father insisted he wasn’t a writer. But when I read him on the page I can still hear him speak

- Share via

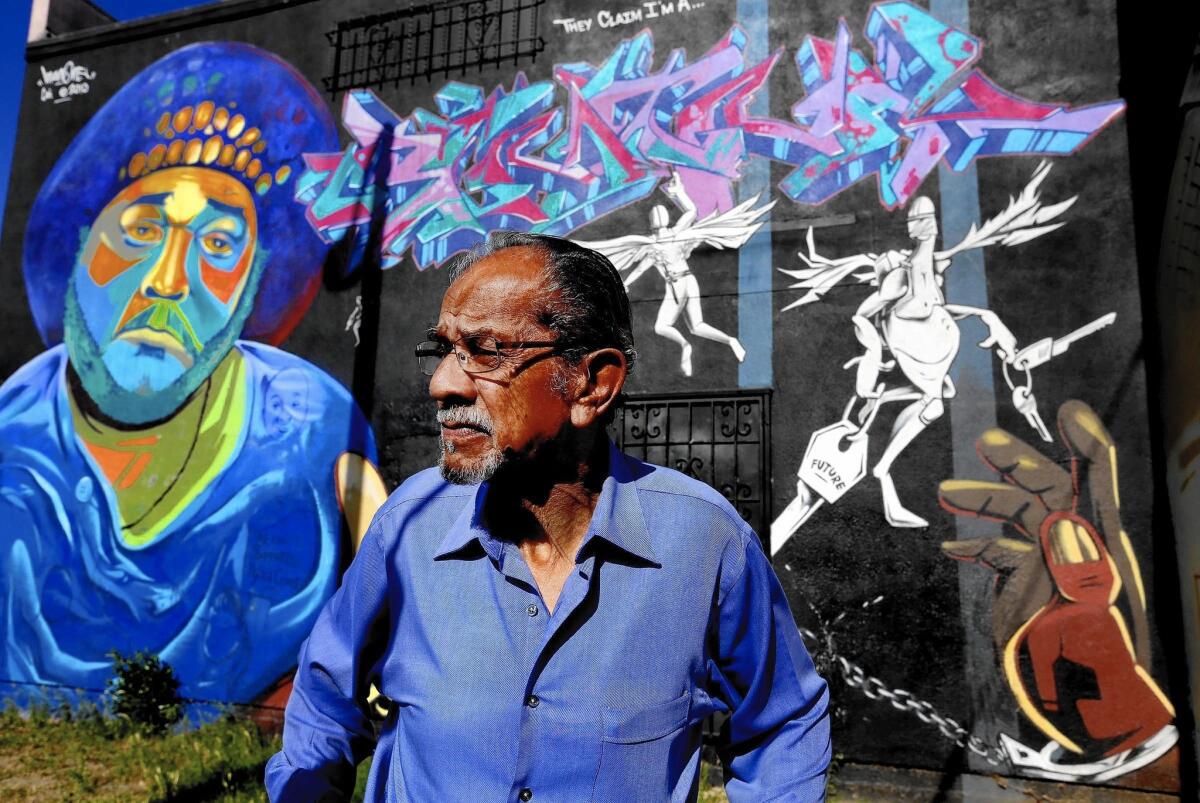

My father Larry Aubry, who died this month at 86, was many things in his life — a probation officer, human relations consultant, education consultant, racial justice activist. He was also a columnist. He wrote weekly for the Los Angeles Sentinel for 33 years, logging an incredible 1,700-plus columns. Yet he insisted he was not a writer. That distinction belonged to me, he said.

It was true he wasn’t a good writer, mechanically. Daddy never learned to type, and his handwriting could be nearly illegible, even to him. His letters were a tortured hybrid of upper and lower case, dashed out in black ink in quick, nervous strokes that he would repeat several times, or cross out altogether; often it seemed like he wasn’t writing so much as drawing or painting. The whole process was arduous: Each week he wrote out his column by hand on a yellow legal pad, then dictated it to my mother — an excellent typist — who entered it into the computer. If I called the house Monday morning — deadline day — my parents would be in the midst of negotiating the gap between what my father ultimately wanted to say with his 800 words and what my mother was typing. “Wow,” he’d say to me after he finished. “That’s hard for me. Not like it is for you.”

Despite his disavowal of being a writer, he understood writing was an art. I think he liked the arduousness of the process. He liked trying to get it right, to channel into few words the many facts, opinions and passions he harbored in any given week. I would say that he saw journalism as poetry, as I did — the art of compressing enormous, disparate things into a coherent whole, in your own voice, in 800 words. His particular voice was straightforward, often informational: He was not a personality or a stylist. But he was himself, which is the hardest thing to get right in writing. And his straightforwardness was certainly not without feeling, or fire. Every time I read his words on the page, I could imagine him speaking, even when he used dry-sounding language.

I was envious. One of the criticisms I’ve gotten over the years is that my writing doesn’t “sound” like me. Sometimes that’s a dig at not being black enough, i.e., being too educated and not folksy enough. I’ve learned to dismiss that. But often the people who said they couldn’t hear my voice simply didn’t know what I sound like. They may have read me but had never heard me speak.

Everybody in town knew what my father sounded like, knew his distinctive baritone that was both gruff and elegant, sober — and sobering — but underneath, compassionate. They’d heard him laugh, try to whisper at meetings and fail miserably, tell funny or surreal stories about his work or his life outside activism (my favorite: He and a cousin traveling to Las Vegas in the 1950s in a rickety, non-air-conditioned van, sitting and sweating the whole way on barstool-like chairs nailed to the van floor.) As a speaker, he was definitely poetic — whether on script or off the cuff, none of the words he said at podiums were wasted or random. Always they were deeply felt. I admired that kind of efficiency, that certainty.

As a writer my father was focused, and meticulous, which sometimes made me feel messy and undone. In my own esoteric musings about the struggle, I often feel myself veering too close to the despair or fatigue that was an anathema to him.

But he understood those emotions. He even empathized; in his long career he had known plenty of dispirited souls. But his lens was longer and wider than mine, not least because he’d been a probation officer, and after that a human relations consultant who studied racial dynamics not from afar in an office, but in the streets. He knew with certainty that black people could live through frustration and despair and come out on the other side. He wasn’t fazed by the crises of the new age, which weren’t really new, such as the forbidding racial stereotypes that framed gangsta rap in the ’90s and aughts and became a running culture debate. His take? Many young black men wearing sagging pants and hard looks are actually vulnerable, tragically lacking in self- esteem. Though he didn’t excuse bad behavior, he cautioned against taking black people at face value, judging them chiefly on how they look (or sound). In his columns my father pushed back on that kind of devaluing, because it never went away.

Because my father and I both wrote for newspapers about similar subjects, people in the community liked to say that I was following closely in his footsteps. I was always gratified by the idea, but found it hard to accept. I was never my father, never could be. I feel like my dog, Honey, who from the beginning of her life adored my oldest dog, Maude. When Maude died suddenly a year and half ago, Honey became the oldest. But she never filled the position of lead dog; she was simply herself, a dog of a certain age and temperament who continues to grieve for the dog before her. Though she occupies Maude’s place, she is not Maude by any stretch.

I don’t like this new position. I wasn’t my father but I liked living in the great shadow he cast, was proud of it. With him gone I feel exposed on all sides; the absence of his voice makes mine seem smaller. My only comfort is knowing that my father wouldn’t agree with me on this — in fact, he would strenuously disagree. Smaller? he would say. Preposterous. As a writer, he knew.

Erin Aubry Kaplan is a contributing writer to Opinion.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.