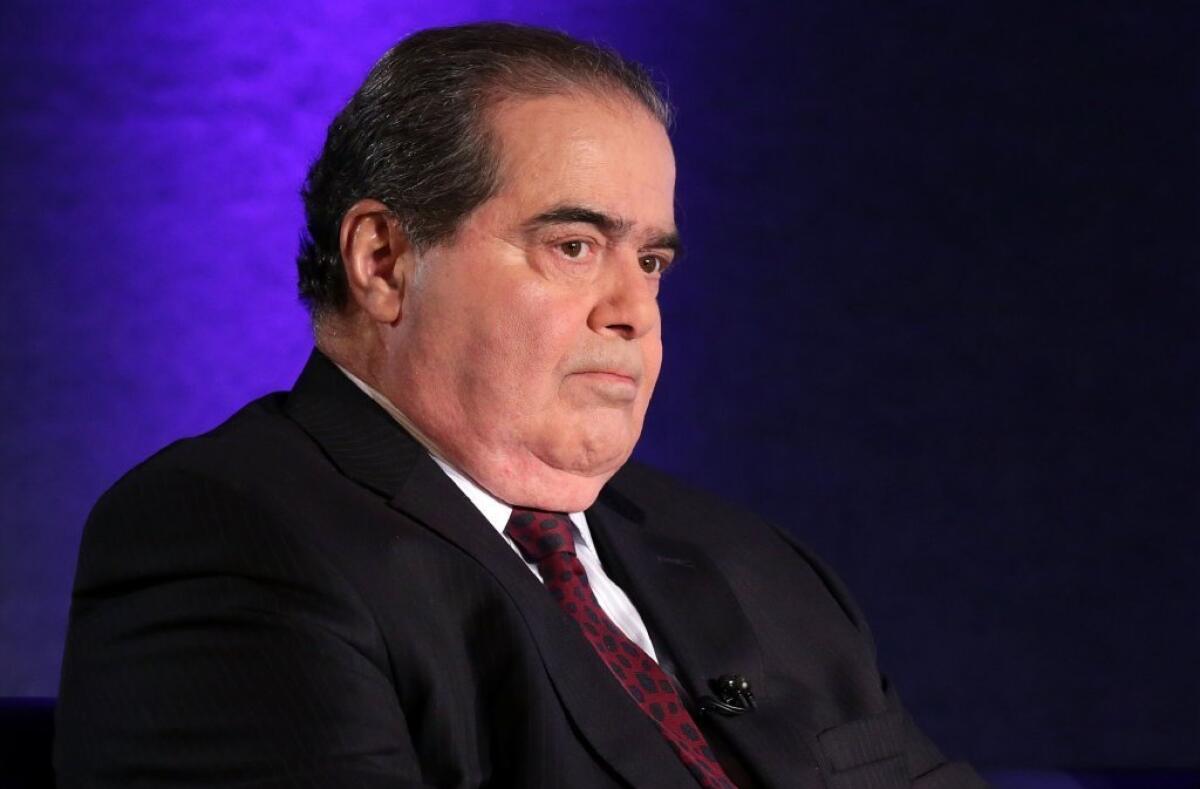

Opinion: More snark from Scalia in a church-state case

- Share via

Whatever else you think about him, Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia has a punchy prose style and a flair for sarcasm.

In his dissent in last year’s decision overturning the federal Defense of Marriage Act, which defined marriage as the union of one man and one woman, Scalia denounced the “legalistic argle-bargle” of Justice Anthony M. Kennedy’s majority opinion. (The opinion was something of an analytic mess.)

Scalia’s latest salvo came Monday in his dissent from the court’s decision not to disturb a ruling that a Wisconsin school district violated the 1st Amendment when it held its graduation ceremonies in the sanctuary of a church, under the shadow of a large cross.

Scalia wrote:

“Some there are — many, perhaps — who are offended by public displays of religion. Religion, they believe, is a personal matter; if it must be given external manifestation, that should not occur in public places where others may be offended. I can understand that attitude: It parallels my own toward the playing in public of rock music or Stravinsky. And I too am especially annoyed when the intrusion upon my inner peace occurs while I am part of a captive audience, as on a municipal bus or in the waiting room of a public agency.”

But Scalia suggested that neither his discomfort, nor that of a high school student forced to graduate in a church of a different faith from his own, amounted to a violation of the 1st Amendment.

Scalia wasn’t the first judge to riff on this subject. In his dissent from the federal appeals court ruling against the school district, Circuit Judge Frank Easterbrook wrote:

“Elmbrook Church is full of religious symbols — but any space is full of symbols. Suppose the School District had rented the United Center, home of the Chicago Bulls and the Chicago Blackhawks. A larger-than-life statue of Michael Jordan stands outside; United Airlines’ logo is huge. No one would believe that the school district had established basketball as its official sport or United Airlines as its official air carrier, let alone sanctified Michael Jordan. And if the district had rented the ballroom at a Hilton hotel, this would not have endorsed the Hilton chain or ballroom dancing.”

This is good stuff, and the Michael Jordan statue is an even cleverer analogy than Scalia’s reference to being subjected to unwanted rock or symphonic music.

But both analogies limp as legal arguments. The Constitution doesn’t prohibit government establishment of a style of music or a basketball team; it does prohibit laws (or state policies) that establish religion. To equate establishment of religion with establishment of music or basketball is argle-bargle.

Follow Michael McGough on Twitter @MichaelMcGough3

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.