American Apparel’s T-shirt just made for controversy, period

- Share via

It may be the most famous T-shirt you never saw. We can’t even show it to you here.

But you can see it here.

It’s called “period power,” and its image is a colored line drawing illustrating a woman’s labial area during menstruation.

The shirt became a pop culture trope after American Apparel put it up for sale on its website, where it can’t be found now — “sold out” is the likelier answer than “taken down.”

It’s an image that would have shocked a 1960s’ girls-only school health class, where they favored dainty euphemisms and vague drawings. This image, by artist Petra Collins and illustrator Alice Lancaster, has provoked reaction far beyond the usual initial “ew.”

Is it powerful and frank and assertive? Or is it vulgar? And can it be both?

Beginning decades ago, the women’s movement protested both women being turned into visual sex-toy objects and to their actual bodies being sanitized and airbrushed. If you judged only by Playboy magazine, you’d think human females didn’t start growing pubic hair until 1971, when Playboy finally showed it. Some among the generation of boys raised on those unthreatening skin pictures were probably stunned to start their actual sex lives with the discovery that women have pubic hair.

The 19th century English artist and esthete John Ruskin was reportedly so grossed out by the sight of his wife’s body on their wedding night that he never consummated the marriage, which was presently annulled. As his wife later wrote to her parents, “he had imagined women were quite different to what he saw I was, and that the reason he did not make me his wife was because he was disgusted with my person the first evening 10th April.”

Doctors used to examine women patients discreetly, through layers of clothing or bedding, which couldn’t have helped a diagnosis.

In Lucy Worsley’s book “If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home,” she writes about the backstory of menstrual mechanics, and notes that when “The Curse,” the first cultural history of menstruation, was published in 1976, one of its authors addressed a meeting of psychiatrists and deliberately mentioned that she was having her period. Some in the group — trained medical doctors, mind you — were shocked. TMI! Why, one of them told the author, “My own wife doesn’t tell me when she is menstruating.”

If coyness played into objectifying women and glossing over their actual body functions, could in-your-face frankness like this sort help women claim their own bodies, and sexuality? Who holds the power? At its most ridiculous iteration, it’s Miley Cyrus naked astride a wrecking ball. At the other end, some millennial women argue, they should be able to be as sexually forthright — as sexually reckless, even — as men are, with no more serious consequences.

For hundreds of years, rape was so often regarded as a crime in which the victim was complicit — and still is in certain parts of the world — that its victims weren’t identified for fear of the shame it brought them.

A now-dead Times colleague used to work at a Bay Area newspaper where, in the fashion of the day — the 1950s and ’60s — rape victims weren’t identified, and in print, it wasn’t even called rape.

The newspaper euphemism was “harmed.” That worked, my friend told me, until the day they ran a story saying that a woman, a crime victim, had been tied up, beaten and stabbed — but not “harmed.” Rape victims’ courage in being forthright about the violent crime committed on them has helped all women, and the criminal justice system, come to terms with rape.

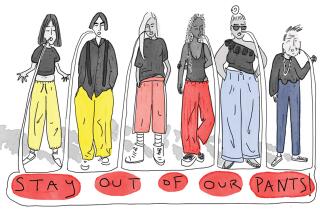

A tampon ad that isn’t all flowers and butterflies kicked up a similar conversation and controversy over the summer. It was funny and gutsy, and you can bet that thousands of mothers of pre-teens are bookmarking the site for a little help in delivering “the talk” to their girls.

The “period power” T-shirt might nudge the conversation along too — just so long as it is worn with PG-13 and NSFW in mind.

ALSO:

Jon Christensen, the man behind Boom

Obamacare: Don’t trust anyone over 60?

Photo essay: Five women more newsworthy than Miley

Follow Patt Morrison on Twitter @pattmlatimes

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.