Egypt’s constitutional crisis

- Share via

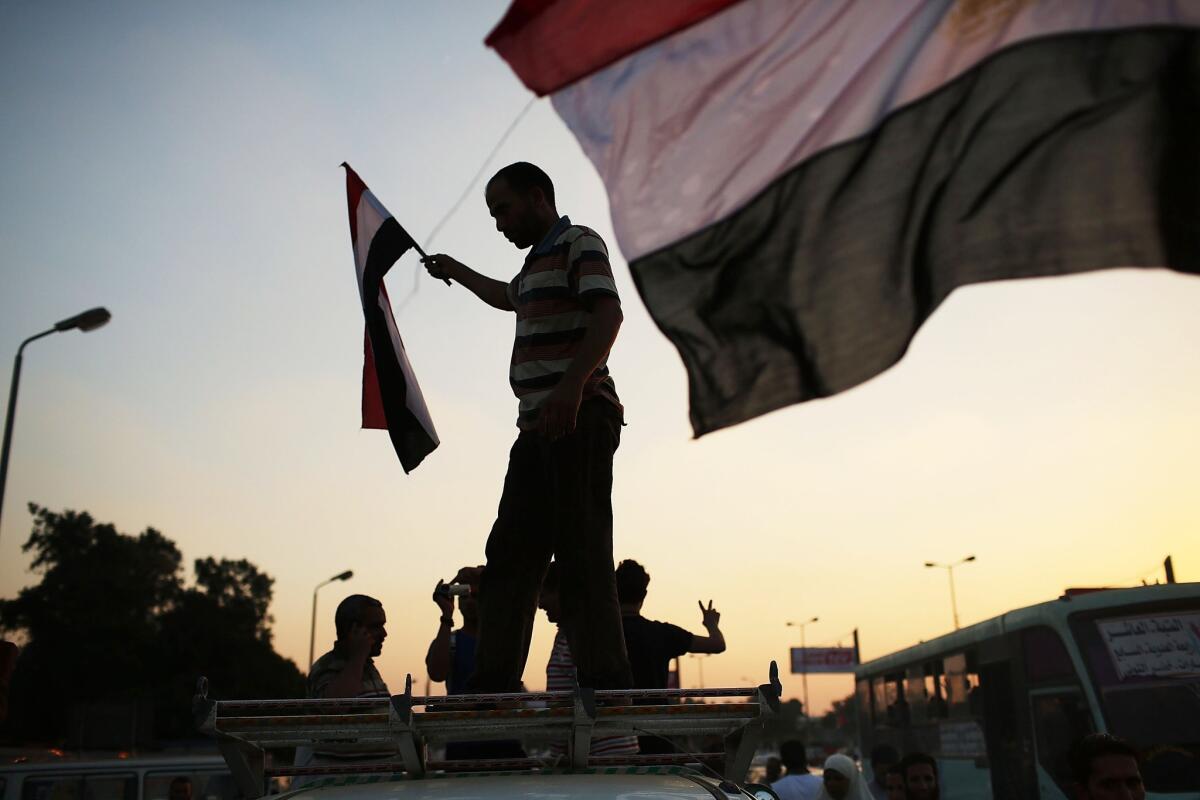

How can Egyptians and the world stem the tide of violence and chaos that has engulfed the country since the military’s removal of President Mohamed Morsi? The answer depends on the success of Egypt’s new constitutional process.

Critics of the military’s constitutional declaration in July have largely focused on particular features of the proposed text, including the provisions backing sharia or the powers of the presidency. But a well-designed, inclusive process would help heal the wounds of the recent turmoil and play a key role in determining the legitimacy and stability of Egyptian democracy. A poorly thought-out process, like the one Egypt went through in 2012, could inflict a mortal wound to the fledgling democracy.

The making of Egypt’s 2012 constitution was a democratic debacle. Morsi’s Nov. 22 edict preventing the courts from challenging laws or decrees until the constitution was complete is now widely recognized as his real coup de grace. The proclamation signaled Morsi’s disregard of popular consensus and refusal to deliberate and compromise over the text. It triggered massive protests and complaints that the president was setting himself up as a new “pharaoh.” The people largely perceived the resulting constitution as illegitimate. In June, Egypt’s Supreme Constitutional Court held that the Muslim Brotherhood-dominated upper house of parliament and the constituent assembly — the committee that drafted the constitution — were unconstitutional, precipitating the current upheaval.

Revolution 2.0 will be better than beta only if the new constitutional process includes broad participation and representation from all social and political groups — including the Brotherhood, which will not disappear as a political force any time soon. Such an inclusive, consensual approach has been an integral part of nearly every successful transition from military rule to democracy. Even in a society as divided as post-apartheid South Africa, an inclusive process helped the population heal from violence by giving traditionally unrepresented groups political voice.

Egypt’s military and secular groups must avoid the temptation to shut the Brotherhood and other Islamist elements out of constitution-making. The new text will not succeed without buy-in from all significant political factions. This will require compromises on the text. It is more important to draft a document that is accepted by a broad swath of the population than it is to have the text judged perfect by international groups.

The parties can help ensure that the process reflects a consensus rather than imposition by a simple majority by writing rules that restrain the most powerful political groups while making sure that they deliberate and compromise with other factions. The new constituent assembly need not — and should not — be popularly elected. An elected assembly would merely ratify the dominance of the best-organized political groupings. It must instead be selected using transparent criteria that promote broad representation of all major political forces, women and minority groups.

Further, to safeguard minority rights, the text should first be negotiated and approved by a large super-majority of assembly members before being put to the voters for approval. Although public ratification can be an important part of achieving true consensus, it is not a substitute for deliberation by all the major players. Approval of the failed 2012 constitution by a majority of voters in an after-the-fact referendum did very little to salvage an otherwise flawed process.

Finally, though the military’s attempts to impose a set of “principles” on the constitution-making process have been rightly derided as a clumsy attempt at self-protection, a truly negotiated set of ground rules may help improve Egyptian democracy. In South Africa, the old regime and newly empowered actors agreed on a set of basic ideals to govern the process. The new Constitutional Court supervised the process by determining whether the new constitution met those standards. This kind of constraint assured competing factions that the constitution would contain protections against the excesses of majoritarian rule.

A similar model might be used in Egypt: Leaders from the Brotherhood, the military, secular groups and other key actors could agree on ground rules, and the well-respected judiciary could oversee compliance. This would foster buy-in from competing factions that would help pacify their supporters and set up an independent and credible arbiter for their interests. It is no accident that the head of the Supreme Constitutional Court was chosen as Egypt’s interim leader. Strong public trust in the Egyptian judiciary is an asset that should be embraced.

The United States and other nations interested in promoting Egyptian democracy should use their leverage to promote an inclusive constitution-writing process. Although some aspects of American constitutionalism have fallen out of favor internationally, our constitutional emphasis on protection against the excesses of majority rule commands wide respect abroad. This is not to say that the Egyptian product should mirror the U.S. constitution — Egypt should write its own rules. But broad consensus on the new rules of the game will go a long way toward making Egyptian democracy work.

Jill Goldenziel is a research fellow at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government; David Landau is associate dean for international programs and an assistant professor at Florida State University College of Law.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.