Newsletter: The feds finally indict Trump. In defense of the slow process that led to this

- Share via

Good morning. I’m Paul Thornton, and it is Saturday, June 10, 2023. Let’s look back at the week in Opinion.

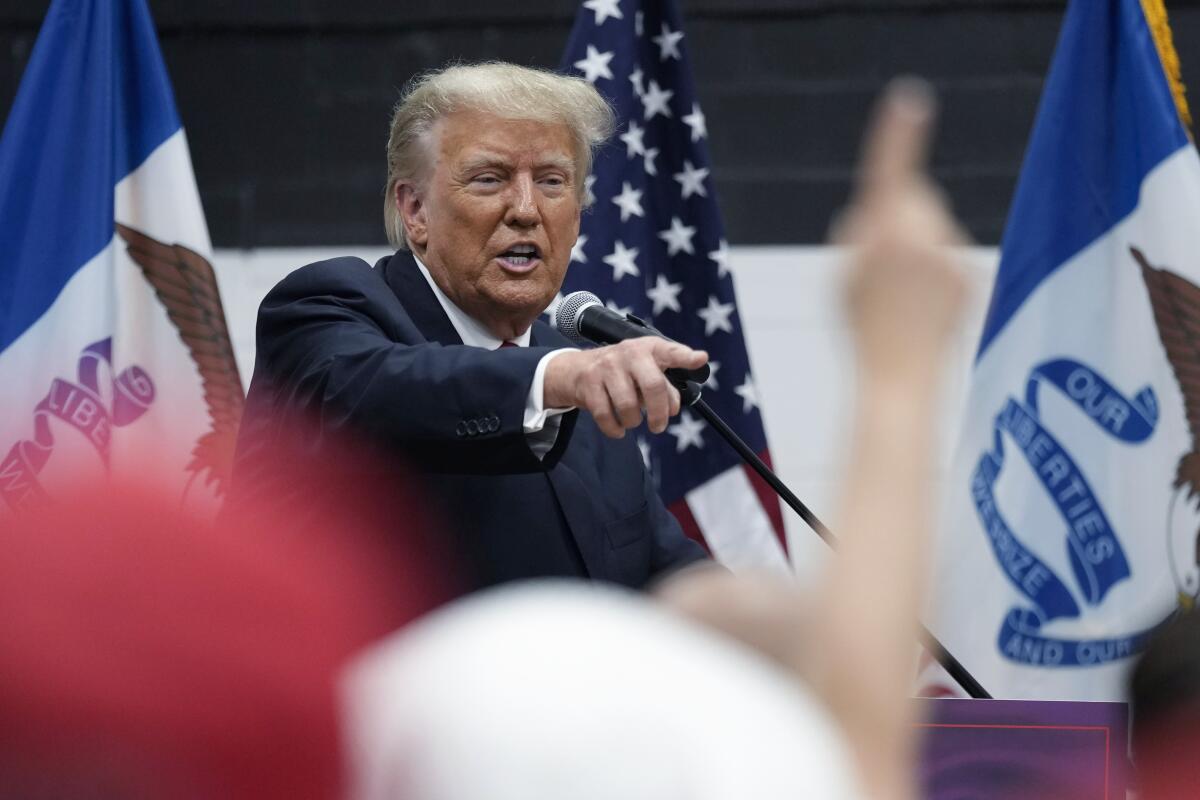

Former President Trump has been indicted by the U.S. Department of Justice. He had already been charged with felonies in New York state court; his latest indictment, in connection with the investigation into his handling of classified information, is at the federal level, marking the first time in U.S. history that a president has been accused of committing a crime by the government he once led.

In my view, Trump all but asked to be arrested when he admitted taking government documents from the White House and suggested a president could declassify material based solely on where he took them or merely by thinking they are declassified. This doesn’t even cover his role in the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection, for which Trump could still be prosecuted (as The Times’ editorial board said last year that he should be).

The deliberate process leading to this moment frustrated plenty of people who said plenty of evidence existed to justify charging Trump well before he became a candidate for 2024. Though I sympathize with that feeling, I’ve argued here before that a plodding investigation serves justice better by removing any good-faith concern of a slipshod, politically motivated prosecution. Carefully following a process respects the rule of law, which Trump wants to blow up.

But I’m no expert. There’s plenty of commentary on this, starting with our own legal affairs columnist Harry Litman, a former U.S. attorney and former deputy attorney general. He says the indictment, breathtaking as it may be, is the inevitable result of a process:

“The months and years of questions about whether the Biden administration should or would indict the 45th and would-be next president — and whether the department would stay its hand for politics, the good of the republic or some other reason — were settled when Atty. Gen. Merrick Garland appointed Jack Smith special counsel.

“From that point on, the investigation of the former president’s retention of classified documents has followed the well-worn path that the federal government would tread for any defendant accused of behavior anywhere close to as brazen as Trump’s over the last two years. Smith pursued the case as he would have any other, and that led ineluctably to today’s indictment.”

Looking at Litman’s past pieces on the Trump investigation, I see the aggregate of his commentary as counseling patience. Just two weeks ago, he said Justice Department special counsel Jack Smith was not only building a case strong enough to charge Trump, but also to anticipate his defense:

“The documents case is at its core straightforward. The former president allegedly took government documents from the White House, which is one sort of crime; and, more flagrantly, failed to comply with a subpoena for those documents, lied about them and otherwise impeded federal authorities, which is another. Smith has long since assembled a formidable case that Trump did so despite knowing his conduct was against the law.

“Judging by Smith’s recent flurry of activity, however, it seems the special counsel wanted to use the investigative powers of the grand jury for all they’re worth before asking it to return an indictment.

“A grand jury’s defining function is to indict. But for prosecutors, the grand jury also has an indispensable investigative function, issuing subpoenas and hearing testimony from any relevant and available witness the prosecution chooses to call. For Smith, it’s an opportunity to probe Trump’s anticipated defenses, lock in witnesses’ stories and pursue investigative avenues that might or might not pan out.”

Soon, we’ll find out if months of meticulous evidence gathering and, well, process following yield a conviction.

Migrants flown to Sacramento are human beings, not political pawns. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’ latest abomination would have led this newsletter if it weren’t for the Trump indictment. Our editorial board makes a point about this atrocity that’s so obvious, it’s a shame it needs to be written: “Let’s be clear — migrants are human beings, not cargo to be shipped around without regard for their humanity.”

DeSantis picks an immigration fight with Gov. Gavin Newsom because he’s scared to attack Trump. Why would DeSantis send a planeload of asylum seekers to California, which has the nation’s busiest border crossing and relies on migrant labor for its economy? Robin Abcarian fingers GOP presidential politics: “With the Republican presidential contest in full swing, DeSantis’ targeting of Newsom with what is fast becoming a tired gambit counts as simple misplaced aggression. He’s posturing for conservative and independent voters in a way that won’t provoke Trump.”

This week’s Supreme Court ruling on voting rights was a shock. UC Berkeley Law School Dean Erwin Chemerinsky welcomes the 5-4 ruling in Allen vs. Milligan, which requires Alabama to redraw its congressional districts because the Voting Rights Act of 1965 indeed prevents racial discrimination in redistricting. But he notes that this ruling comes against a backdrop of years of the court needlessly weakening the law.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Can a four-day workweek really work? Many companies have already learned the answer. And the answer, according to sociologists Juliet Schor and Wen Fan, is yes: “In Europe, national and regional governments have pilot four-day week programs in progress, and the United Arab Emirates has shifted public-sector employees to a 4 ½-day schedule. In February, we released findings from the world’s largest trial of a four-day week with no reduction in pay, involving some 60 organizations in Britain across a range of sectors from public relations to healthcare to manufacturing. The results were striking: Employees and companies using the new schedule are thriving.”

A Hollywood mess: Writers are striking, and actors may too, over the future of the industry. Both unionized writers and actors in the entertainment industry worry about rapidly advancing artificial intelligence jeopardizing their jobs. Workers deserve protection, but the standoff between studios and unions isn’t serving either side, says the editorial board: “No one can say whether AI could replace writers and actors or will just replace some tasks and complement creators’ work. This fight won’t be easily resolved when the technology is so quickly evolving. Nevertheless, the unions and studios should be at the negotiating table — along with AI experts — to come up with a reasonable framework that provides basic protections in these early days.”

More from this week in Opinion

From our columnists

- LZ Granderson: The GOP wants us to fear “President Harris.” Here’s how Biden should respond

- Jonah Goldberg: Why Trump’s childish bullying of his Republican opponents works

- Nicholas Goldberg: What happened to criminal justice reform?

From the Op-Ed desk

- We’ve made huge advances against COVID. Why is it still killing so many people?

- What the film “Flamin’ Hot” can teach Hollywood about the perils of neglecting Latinos

- Menopause doesn’t have to be miserable

From the Editorial Board

- Forcing treatment on mentally ill homeless people is a bad idea

- Cleaning up California’s oilfields may cost $21.5 billion. Taxpayers shouldn’t get the bill

- I helped break the Arnold Schwarzenegger groping story. It took him 20 years to own it

Letters to the Editor

- I saw anti-LGBTQ+ hate outside Saticoy Elementary, not concerned parenting

- California doesn’t have a homeowner insurance crisis. It has a climate crisis

- Steve Garvey is an ideal Republican to run for senator. That isn’t a compliment

Stay in touch.

If you’ve made it this far, you’re the kind of reader who’d benefit from subscribing to our other newsletters and to The Times.

As always, you can share your feedback by emailing me at [email protected].

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.