Editorial: Britain moving too fast on 3-parent children

- Share via

A procedure newly approved in Britain allows babies to be conceived with DNA from three parents — a mix of DNA that would determine the child’s characteristics and become part of the gene pool in future generations. Last year, a U.S. Food and Drug Administration advisory panel wisely decided that this procedure, designed to overcome the devastating effects of mitochondrial disease, wasn’t ready for human trials, much less therapeutic use. With its premature approval, Britain has opened the way for three-parent children around the world, because anyone with enough money can travel there for the procedure.

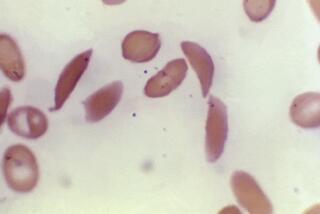

Mitochondria are the specialized compartments within cells that are responsible for creating most of the energy needed by the body. But when a mother’s mitochondria are faulty, the resulting disorder can be disabling or fatal to her offspring. Children born with mitochondrial disorder might lose muscle control, suffer muscle weakness and pain, have difficulty breathing and be beset by heart and liver problems.

Researchers hope to overcome this by removing the nucleus from the egg of a woman who has the disorder and adding it to the healthy mitochondria from another woman’s egg. Fertilization is done in vitro. Mitochondria contain a small amount of DNA — thus, children would be born who are perfectly healthy but who also carry the genetic material of three parents and would pass that mix on to their progeny.

Could this result in unforeseen ailments far in the future? Skeptics of the technology raise concerns about the possibility of mismatches between the DNA of the women who provide the nucleus and those who provide the mitochondria. They worry about the inadvertent introduction of new genetic abnormalities and point out that an attempt to create human embryos using this procedure resulted in half the eggs undergoing abnormal fertilization.

Several rhesus monkeys, apparently healthy, have been born after the procedure in research trials in Oregon, but they have not yet lived out their life spans; scientists simply do not know what the results will be over generations, or in much larger trial groups.

Cellular and genetic manipulation may hold the keys to saving lives and relieving enormous suffering. Research should be encouraged yet must go slowly, with no ethical or scientific step skipped, lest it lead to irreversible consequences for subsequent generations.

Most governments, including the European Union, recognize the importance of approaching this kind of work cautiously. Unfortunately, Britain’s ill-advised action has flung wide a door that should have been opened inch by inch.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.