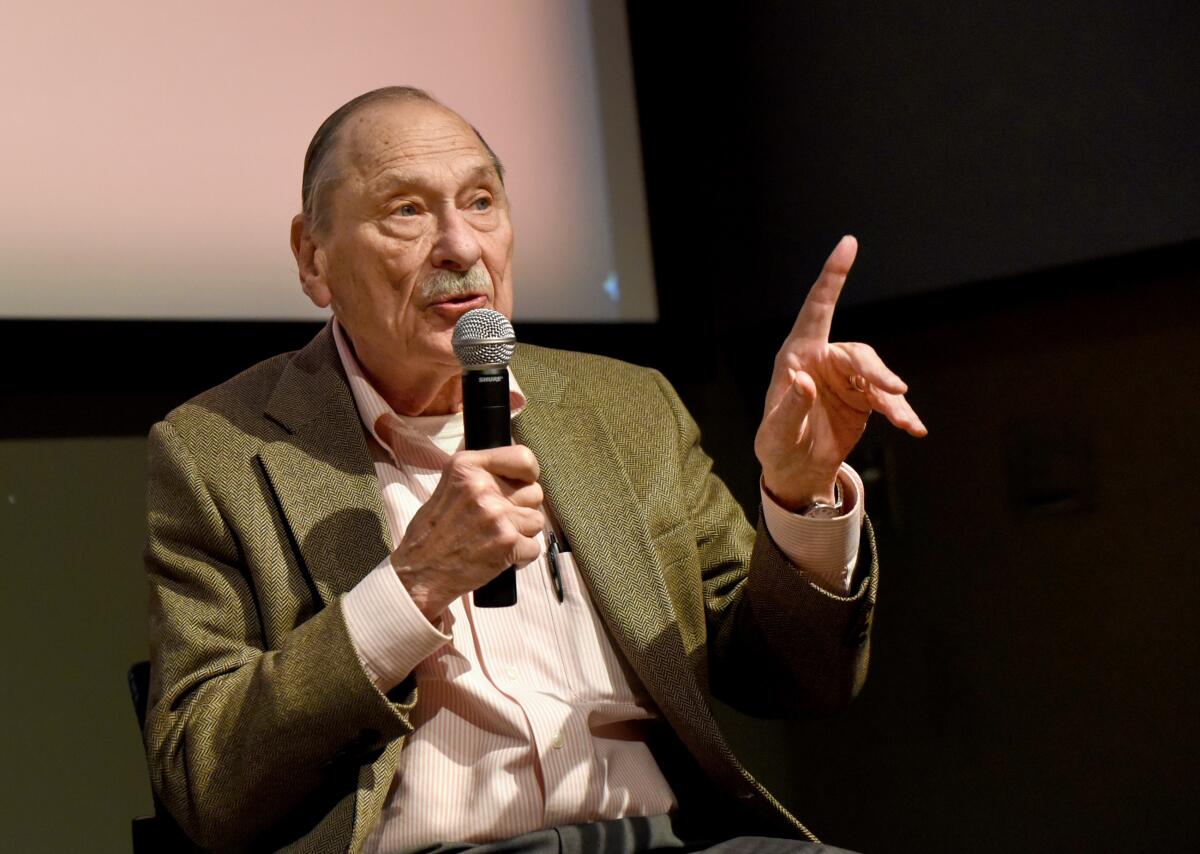

Mel Opotowsky, newspaper editor and 1st Amendment advocate, dies at 92

- Share via

Maurice Leon “Mel” Opotowsky, a former newspaper editor and tenacious free press advocate who was known for helping to advance 1st Amendment rights, has died.

Opotowsky died April 18 at Claremont Manor retirement community, where he lived with his wife, Bonnie Opotowsky, according to their son, Didier Opotowsky. He said his father’s cause of death is not certain, and that he had Parkinson’s. He was 92.

Opotowsky was a top editor at the Riverside Press-Enterprise when the paper brought two cases before the U.S. Supreme Court that resulted in landmark rulings advancing the public’s right to view certain legal proceedings. He was later a founding board member of the First Amendment Coalition, a nonprofit dedicated to protecting the free press and preserving access to government records and meetings.

“I don’t know that there’s another single person in California who had such a positive and long-lasting impact on open government in our state,” said David Snyder, executive director of the First Amendment Coalition. Opotowsky remained an active board member until his death and had emailed Snyder suggesting work the organization could take up just weeks ago, he added. “His longevity, his persistence and his tenacity are the stuff of legend.”

Opotowsky joined the Press-Enterprise in 1973 after working as an editor at Newsday. He was known for fostering a culture that emphasized hard news and accountability journalism, said former columnist Dan Bernstein, who worked at the Press-Enterprise from 1976 to 2014.

Back then, the news organization put out two papers: the morning Enterprise and the afternoon Press, which were later merged. Opotowsky eventually climbed the ranks to become managing editor of the combined edition.

“He was pretty much on everybody’s shoulder as they wrote and reported stories, because he was a very tough and aggressive editor who was skeptical of government and skeptical of politicians,” Bernstein said. “And none of us wanted to be left not asking the question that he would have looked for immediately.”

Terry Anderson, the Associated Press correspondent who became one of America’s longest-held hostages after his capture by Hezbollah, has died.

In January 1984, the paper won the first of two Supreme Court rulings that are still often cited by attorneys seeking access to court proceedings. Albert Greenwood Brown Jr. was on trial for the kidnapping, rape and murder of 15-year-old Susan Jordan, whose body was found in an orange grove near her Riverside high school. When it came time for jury selection, the judge closed the courtroom.

After challenging the move, the Press-Enterprise successfully won a 9-0 ruling giving members of the public and press the presumed and constitutional right to attend jury selection, said Bernstein, who wrote a book about the proceedings called “Justice in Plain Sight: How a Small-Town Newspaper and Its Unlikely Lawyer Opened America’s Courtrooms.”

Roughly two and a half years later, the paper won a second Supreme Court ruling affirming that preliminary hearings should be open to the public. That was after a challenge stemming from the case of Robert Diaz, a Riverside County nurse who had killed at least 12 patients by injecting them with lidocaine.

Opotowsky was involved in both challenges — particularly the second, for which he served as the Press-Enterprise’s point man, Bernstein said. He would often rewrite portions of legal briefs, he added.

“He was reputed to know as much about constitutional law as a lot of lawyers did,” he said. “Whether it was government meetings, courtrooms or records, he was pretty much adamant that all records should be open and all courtrooms should be open.”

One or both of the rulings have been cited as precedents in a slew of high-profile proceedings, including those related to the Oklahoma City bombing, 9/11, the Boston Marathon bombing, the Aurora, Colo., theater shooting and Martha Stewart’s perjury case, Bernstein said.

The Supreme Court, significantly expanding access to the courtroom, ruled Monday that the public has a constitutional right to attend pretrial hearings in criminal cases.

Opotowsky retired as editor of the Press-Enterprise in 1999, becoming an ombudsman, tasked with investigating and responding to reader complaints. In addition to his open records advocacy work, he taught at Cal State Fullerton.

He was rightly known for being unsparingly direct, said Kris Lovekin, a former education reporter at the Press-Enterprise. She recalled one story in which Opotowsky demanded that a reporter unmask a donor to UC Riverside who wanted to remain anonymous, figuring that a public university must be required to disclose its backers. After he resolved to get an attorney involved, the Press-Enterprise’s then-publisher, Howard H. “Tim” Hays, was forced to disclose that it was he who had, in fact, made the donation, Lovekin said.

At the same time, Opotowsky was also kind and compassionate when warranted, she said. A keen chronicler of the world around him, he was creating journalism up until the end of his life, she said.

“He was still writing stories about people in Claremont Manor, about the people he lived with,” Lovekin said. “He would post it on Facebook and we would read about the other residents.”

Opotowsky was remembered for his dry wit that at times leaned acerbic. He had a soft spot for practical jokes and an even softer spot for his grandchildren and great-grandchildren, his son said. He loved horseback riding, fox hunting and trying different restaurants, he said.

Dickey Betts, a founding member and guitarist for the Allman Brothers Band, died Thursday of cancer and COPD, his family announced. The musician was 80.

Opotowsky was born in New Orleans on Dec. 13, 1931. His mother was ill, so one of her sisters-in-law filled out the registration card and submitted it to the city to produce a birth certificate, Didier Optowsky said. The sister-in-law named him Maurice Leon after their father — contrary to a tradition among some Jewish people that dictates babies should not be named after living relatives, he said.

“My grandmother was so furious she refused to call him Maurice, refused to call him M.L.,” Didier Opotowsky said. “So she called him Mel.”

His father did not learn his legal name until he was drafted into the Army, Didier Opotowsky said.

True to his roots, Opotowsky was also known to make enormous batches of red beans and rice — enough to feed the entire family for weeks, his son said. “They were good,” he said. “But we would get tired after the fifth day or so.”

He is survived by his wife Bonnie; son Didier; daughters Joelle Opotowsky, Keturah Persellin and Jamie Persellin; 18 grandchildren and many great-grandchildren. He is preceded in death by a daughter, Arielle Opotowsky, who died as an infant.

A memorial service has been set for May 18 at Claremont Manor hall.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.