Leo Leonard, PSA co-founder who pushed to reopen probe of deadly 1978 crash, dies

- Share via

Among San Diego aviation buffs, Leo Leonard will always be remembered as a co-founder of PSA, the spunky San Diego-born Pacific Southwest Airlines that flew the California skies from 1949 to 1987. But until his dying day, the 101-year-old aviator pushed to rewrite the history of how some of the pilots he hired during the company’s glory days are remembered.

The World War II veteran died of natural causes at his home in Del Cerro, his family said.

In an interview just three weeks before his death, Leonard said he wanted to honor the 144 lives lost in the Sept. 25, 1978, crash of PSA Flight 182. But his dying wish was to clear the name of Capt. James McFeron, who federal investigators found responsible for the fiery accident, which occurred when the 727 jetliner collided with a Cessna airplane during its final descent over North Park to San Diego International Airport.

“All these people got killed and their families were told that Jim McFeron caused the accident,” Leonard said. “How would you feel if you were his family? He couldn’t have prevented it, but he got the blame because he was dead.”

Leonard was proud of co-founding an airline that brought jobs and prestige to San Diego, as well as other accomplishments that included working post-retirement as a private pilot, co-founding the former Grossmont Bank and owning a 550-acre cattle ranch in central Oregon for more than a decade. But toward the end of his life, he became increasingly haunted by the tragedy of Flight 182.

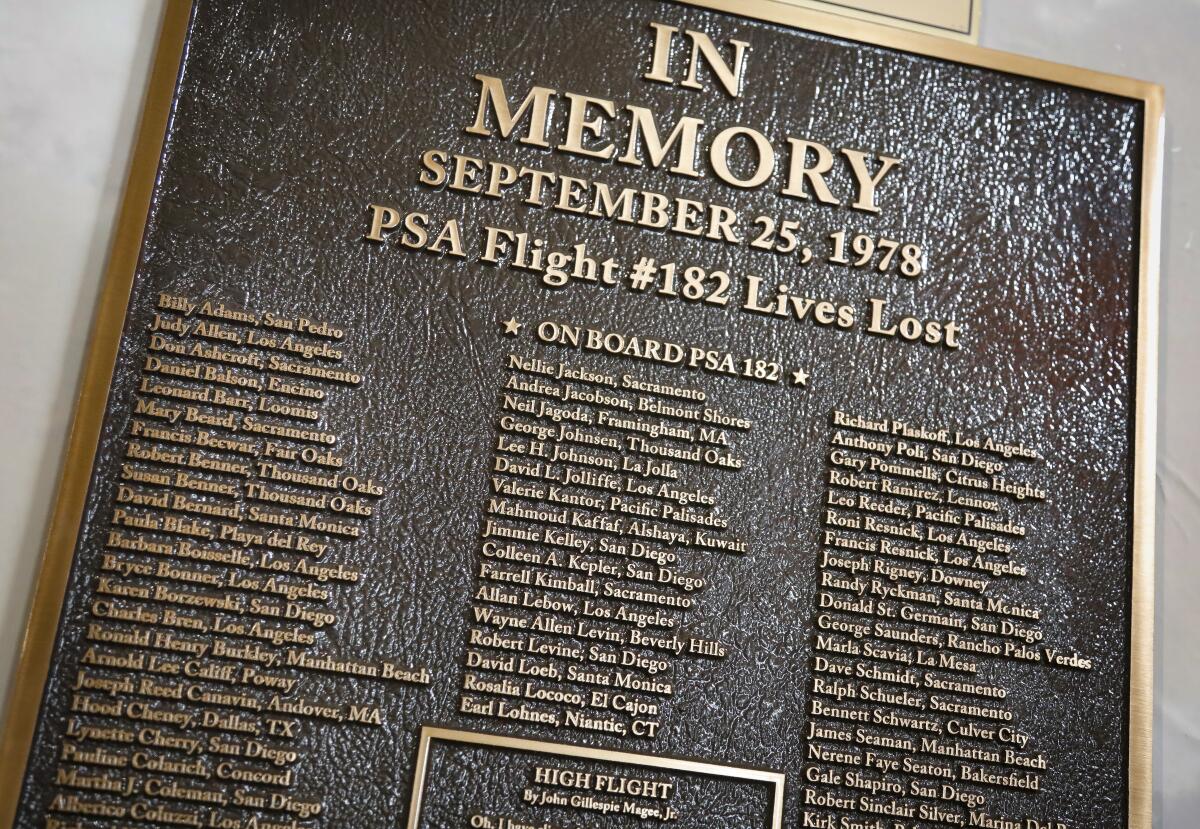

In 2001, he penned a long letter to the San Diego Union-Tribune on the “true story” behind the crash. Three years later, he had a plaque memorializing the Flight 182 victims installed in the PSA exhibit at the San Diego Air & Space Museum. In 2010, he worked with museum officials to expand that exhibit. And in 2019, he spoke to the Union-Tribune about his goal of getting the National Transportation Safety Board to reexamine its findings on the crash.

Leonard believed the air traffic controllers should have warned the PSA crew that the Cessna was underneath the jet’s right wing, but the report blamed the pilot in command for failing to follow approved procedures and maintain visual separation clearance with the smaller plane.

Leonard’s daughter, Lisa Leonard, said her father wanted to see what he felt was a great injustice overturned before he died. But time ran out.

“He was just very sad about that,” she said. “He wanted to have the Federal Aviation Administration come out and say ‘we are to blame,’ but it was never going to happen.”

Leonard was born on Nov. 23, 1919, in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. One of 14 children in his Presbyterian family, he grew up enamored with the airplanes he saw flying overhead as a boy. In his 20s, he got his pilot’s license and eventually followed his brothers out to San Diego in 1939.

When World War II began, he joined the Army Air Corps and worked as an instructor for B-25 bombers and other planes. After the war, he briefly flew cargo for the Flying Tiger Line and in 1946 was hired as instructor for the Friedkin School of Aeronautics in San Diego run by Kenny Friedkin.

Leonard’s longtime next-door neighbors, Greg Scott and Gene Erquiaga, say they enjoyed sitting for hours listening to Leonard’s flying stories and admiring the many photos, plaques and newspaper clippings that line the walls of the Leonards’ hilltop home. Scott — whose father also grew up in Iowa, flew in World War II and worked for the Flying Tigers — said men of that generation lived with the purpose of doing what’s right.

“What marks that generation is what they stood for,” Scott said. “Their honor, their word and their handshake was everything. They had high integrity and purpose. They were all-around great guys.”

Initially, all of the school’s students were war veterans spending their G.I. bill money on flight lessons. But when that money petered out and Friedkin ran out of students in 1949, he came up with the idea of starting his own airline with his instructors. Leonard, who would come to own 40% of the company’s shares as director of flight operations, was at the controls of a leased war surplus Douglas DC-3 plane for PSA’s maiden flight to Oakland on May 6, 1949.

In those early days, Leonard said the fledgling airline was flying by the seat of its pants. It couldn’t afford a berth at Lindbergh Field, so it flew out of a separate terminal, and instead of flying to San Francisco, it flew to a rented quonset hut in Oakland. But business was steady. PSA became known as “poor sailors airlines” because most of its initial passengers were San Diego servicemen on leave, flying to the Bay area for a weekend getaway on a $15.75 fare. Leonard’s wife, Ann, sewed the uniforms for PSA’s first stewardesses.

Eventually, PSA bought its own planes, added flights to Burbank and 11 other California cities and became known as the “friendly airline.” Pilots greeted passengers and kept their cockpit doors open during flights, stewardesses wore miniskirts and PSA’s planes became known as “grinning birds,” because their noses were painted with smiles.

Eventually, PSA would become one of the most profitable regional airlines in the country, but Friedkin wasn’t around to enjoy the success. He died in 1962 at age 47.

Leonard was an avid marathon runner who prided himself on his fitness. But FAA rules at the time didn’t allow pilots to fly past the age of 60-1/2. He was just three months from retirement when Flight 182 went down. He stayed on until the investigation was complete and then retired after making his final flight on Oct. 24, 1979.

Eight years later, PSA was purchased by USAir, which was looking for West Coast gates. Leonard said that if Friedkin had lived, he would never have allowed the sale because of PSA’s importance to the community.

“We were San Diego’s airline,” Leonard said. “We lost a major business that was headquartered here and it was doing well.”

Last month, Leonard asked Scott to reach out to the Union-Tribune for what would be his final interview. Seated by his bed dressed in a suit jacket and his pajamas, Leonard talked about his life’s highs and lows and shared letters, newspaper clippings and the NTSB crash report. He wondered whether another story could be written, or maybe it could be part of his obituary. Summing up his thoughts, Leonard said he wanted to be remembered for challenging the notion that it wasn’t pilot misjudgment that caused the crash but a number of errors in FAA procedures.

“The story needs to get told about how so many people were killed unnecessarily,” he said, “and if it’s the last thing I do, I’m telling it.”

Leonard is survived by his wife and daughter. . He was predeceased by his son, Skip.

Kragen writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.