Charges are dropped against Kenyan suspect

- Share via

NAIROBI, Kenya -- The International Criminal Court’s prosecutor dropped charges of crimes against humanity against a fellow defendant of Kenya’s president-elect Monday, raising questions about whether the case against Uhuru Kenyatta will hold up as he is on the verge of becoming the nation’s leader.

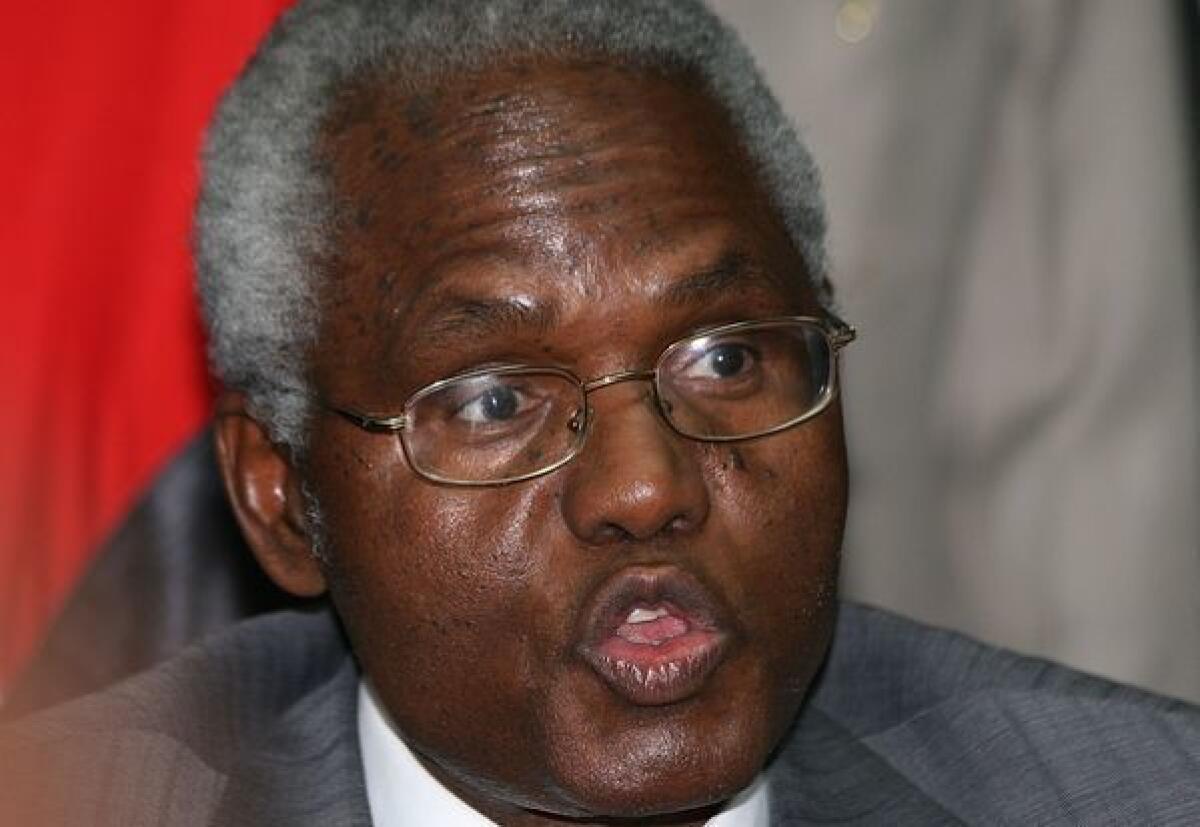

Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda announced that the charges against former public service chief Francis Muthaura had been dropped because a key witness recanted and admitted he had accepted bribes. She said the decision had nothing to do with Kenyatta’s election victory last week.

With the world watching one of the court’s most delicate and politically awkward trials, it is not just Kenyatta who will be on trial when he faces charges of involvement in tribal violence, including murder and rape, that followed elections in 2007. The court too is on trial.

The court’s credibility hinges on its handling of the high-profile case that became a key issue in last week’s election.

In the past, Bensouda has complained that witnesses in the Kenyatta case have been killed, gone missing or have been bribed to recant on evidence given to prosecutors.

She outlined a number of other difficulties Monday that caused the prosecution against Muthaura to collapse: Some witnesses were afraid to testify; others had died. Then there was “the disappointing fact that the government of Kenya failed to provide my office with important evidence, and failed to facilitate our access to critical witnesses who may have shed light on the Muthaura case.”

“Let me be absolutely clear on one point. This decision applies only to Mr. Muthaura. It does not apply to any other case,” she said in a reference to the remaining cases, against Kenyatta, his running mate William Ruto and journalist Joshua arap Sang.

Ruto is facing charges of crimes against humanity, including murder and forcing people from their land and homes, relating to the violence that spread across Kenya in late 2007 and early 2008 after the disputed election.

The decision to drop the charges against Muthaura raises questions about the court’s ability to protect witnesses. With Kenyatta and Ruto about the take control of the state security services and law enforcement agencies, some question whether remaining witnesses will have the courage to stand up against two such powerful men.

Kenyatta’s election places Western leaders in an awkward position. On the one hand, he has been indicted on extremely serious charges. Yet if the election results are confirmed at a Supreme Court hearing in coming weeks, the West would either have to embrace Kenyatta or risk losing its most important partner in a volatile region and a key ally in its war against Al Qaeda extremists.

The stakes for the court are just as high.

“It’s a real test for the ICC. Are they going to be able to see this prosecution through, if you have a case against the head of state? This is going to be where the ICC stands or falls: in Kenya,” said Michela Wrong, author of “It’s Our Turn to Eat,” a book about Kenya’s tribally based politics and system of entrenched patronage. “If the case collapses here, the ICC will be left with very little credibility.

“You are now going to have a concerted effort by the structures of the Kenyan state who are going to be working to undermine this case,” she said. “We know that witness protection has proven to be patchy.”

In 2008, a Kenyan commission investigated the post-election violence and turned the names of suspects over to the government, which did nothing. Luis Moreno-Ocampo, then prosecutor with the ICC, announced in 2009 that he would open an investigation into those responsible for the violence.

The ICC investigation, initially broadly popular in Kenya, became charged with tribal politics during the recent campaign, with Kenyatta and Ruto -- who were on opposing sides in the 2007-08 violence -- forming a political alliance.

In 2009, many Kenyans believed it was better for the ICC to investigate and prosecute the case because Kenya’s court system was too tainted to act, according to Wrong. But the Kenyatta-Ruto political coalition, Jubilee Coalition Alliance, campaigned strongly that the case was cooked up by their political opponents with the help of foreigners to shut them out of power.

“It’s been twisted and turned into something else by the Jubilee team who have done a very successful job of portraying it as a post-Western, post-colonial interference aimed at certain politicians, and their communities rallied loyally around them,” Wrong said.

[Updated at 10:35 a.m., March 11: Some critics have pointed out the problems of allowing ICC defendants to remain at large with the freedom to attack the credibility of the court or potentially intimidate witnesses.

Gladwell Otieno, of the African Center for Open Governance, the nongovernmental anti-corruption organization that is challenging in the nation’s Supreme Court what it sees as deeply flawed election results, said the organization was deeply concerned about the protection of witnesses, given the power of those facing charges.

“The issue here is that you have a government that is not willing to live up to its international obligations,” she said in a phone interview, referring to the Rome statute on which the international court is founded. “Basically the government -- by not cooperating and blocking the ICC at every turn -- is breaking those agreements.”

Patrick Smith, editor of the respected journal Africa Confidential, said in a phone interview it would be “devastating” for the credibility of the ICC if it failed to secure a conviction in the Kenyan cases, or if the cases collapsed. He said it would be a gift to other indicted heads of state, such as Sudanese President Omar Hassan Ahmed Bashir, who could use it to justify their refusal to cooperate.

“It would send a message to many regimes that you can keep on killing your own people, as long as you control your own judicial and security systems, because there’s no alternative [justice system] and the international justice system can’t protect witnesses testifying against indictees.

“It would be a pretty grand failure.”]

ALSO:

Kenyan presidential loser Raila Odinga contests result

Pakistan, Iran launch controversial gas pipeline project

Kenya election over, dispute over outcome heads to Supreme Court

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.