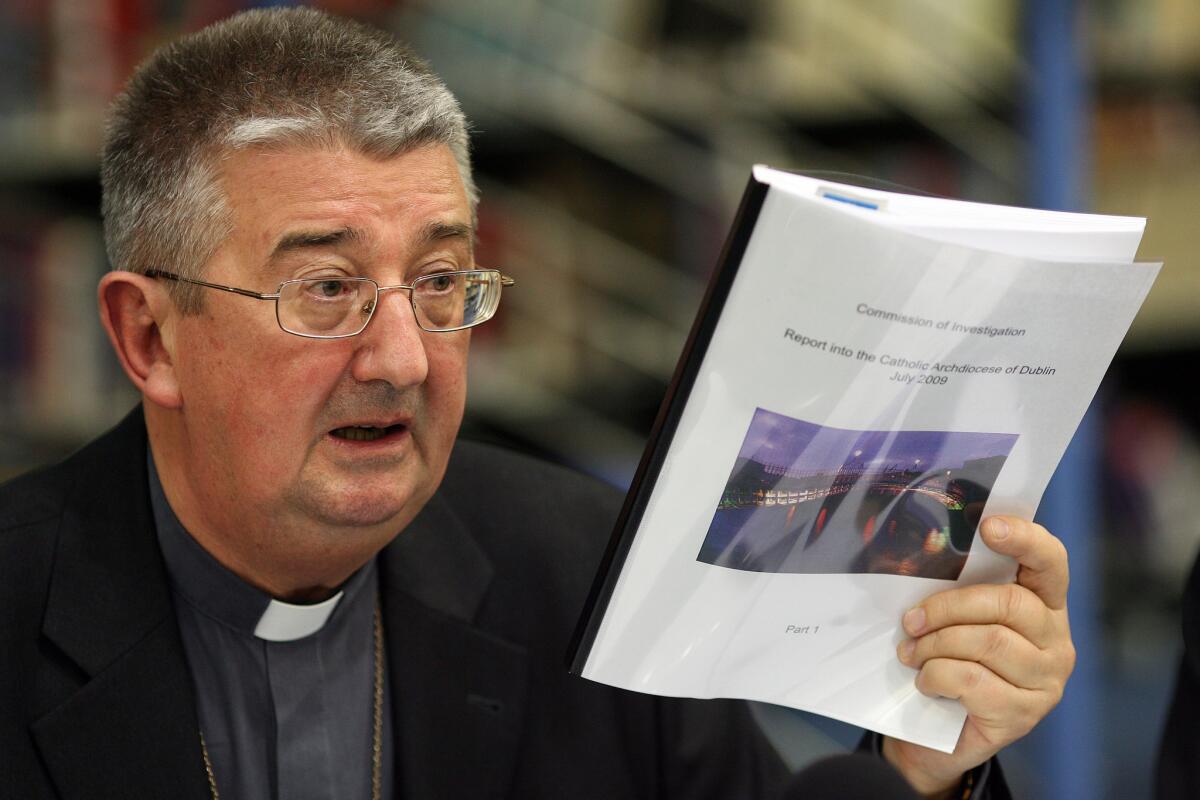

To replace Benedict XVI, Irish Bishop Diarmuid Martin

- Share via

London bookmakers see a contest among Nigeria’s Cardinal Francis Arinze, Marc Ouellet of Canada and Peter Kodwo Appiah Turkson of Ghana, each of whom would present a smiling face of Catholicism as the next pope. (Either of the Africans might also guide the church to a future in the developing world.) Liberals hope for someone like Christoph Schoenborn of Vienna, who seems open to sharing power with laypeople. Some longtime Vatican watchers say the Italians seek to reassert their control, in order to fix the management problems inside the bureaucracy. According to this faction, the church’s finances are a mess and the brand is severely damaged.

But the damage to the church has been done mainly by the never-ending scandal of priests who sexually abuse children and the routine cover-up practiced by higher-level officials, up to and including the pope.

The lowest point in the crisis came with Ireland’s outraged response to revelations of sexual abuse by priests and the cover-up orchestrated by the hierarchy. In 2011, Irish Prime Minister Enda Kenny decried “the dysfunction, disconnection, elitism, the narcissism that dominate the culture of the Vatican to this day.”

More telling was the public response. A 2010 protest march through the streets of Dublin ended at the seat of Irish Catholicism, St. Mary’s Pro-Cathedral. There, more than 1,000 children’s shoes were tied to an iron fence in front of the church. The shoes represented child victims of abuse at the hands of priests. When a bishop appeared to speak with the protesters, he was met with a furious response from men and women who called Irish clerics “child-abusing terrorists” and the church “the largest pedophile ring in Ireland.”

In the world’s most Catholic country, attendance at Sunday services — once standing room only — declined by more than half. In just eight months, more than 6,000 people publicly renounced their faith as part of a project called Count Me Out.

Amid the crisis, only one Irish bishop, Diarmuid Martin, approached the angry and the disillusioned with the kind of humility required. Martin symbolically washed the feet of abuse victims and noted the futility of a “faith built on a faulty structure,” by which he meant the rule of ordained men. “The narrow culture of clericalism has to be eliminated,” he declared. “It did not come out of nowhere, and so we have to address its roots from the time of seminary training onwards.”

This Martin is no Martin Luther. He supports the morality preached from Rome, including its opposition to abortion. These positions might bother anyone looking for rapid change in the church, but they should reassure the orthodox and make it possible for him to be considered a worthy successor of retiring Pope Benedict XVI. In addition, he’s a son of the land that has historically given more priests and nuns to the church, per capita, than any on Earth.

Ireland supplied the priests and the basic culture of Catholicism in America in the 19th and 20th centuries. For better or worse, it was the Irish style of belief and behavior that predominated, especially in big cities and Catholic schools, including Notre Dame University. More recently, one often finds Irish (or Irish American) priests and nuns doing the tough work of serving the poor and standing up to repressive regimes. For this reason, the radical priest in our imaginations, as well as the renegade sister, typically have Irish names.

Of course we find plenty of Irish names — Mahony, Magee, Murphy, etc. — among those clergy who stand disgraced by the international pedophile scandal. But no group has responded to the crisis with more courage and honest outrage than the people of Ireland, and no culture promises more potential for righteous rebellion inside the church.

Intelligent and effective dissent is an Irish trait forged over centuries of suffering, deprivation and repression. I think it dwells inside Martin alongside his genuine shame over the church’s sins. His choice to replace the caretaker Benedict would bring the possibility of renewal to the church in the West, including former strongholds like Ireland, and signal a recognition that today’s crisis won’t be resolved with yesterday’s perspective.

Michael D’Antonio is the author of “Mortal Sins: Sex, Crime and the Era of Catholic Scandal,” to be published in April.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.