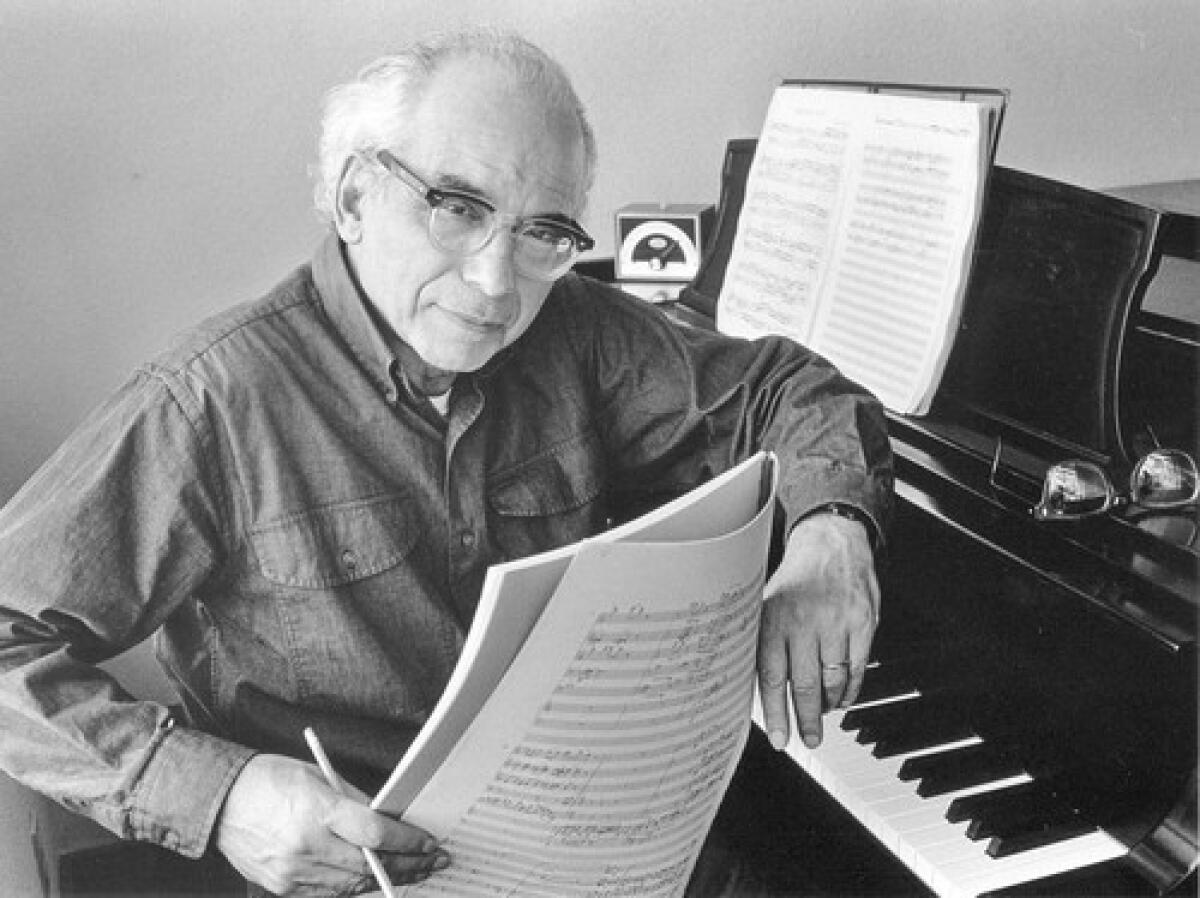

George Perle dies at 93; theorist and composer championed atonal music

- Share via

George Perle, the American music theorist and scholar who was widely regarded as the composer who put a human face on atonal music, has died. He was 93.

Perle died Jan. 23 at his home in New York City after a long illness, according to his wife, Shirley.

Always highly regarded by his peers, Perle began to draw wider public attention only after he won a Pulitzer Prize -- as well as a MacArthur Fellowship -- in 1986 for his Wind Quintet No. 4.

“His music is a special language,” wrote Princeton University composer Paul Lansky, “and while each piece sings uniquely and individually, his language is consistent, convincing and all his own. It reveals no sense of arbitrary abstraction, formalism or the whims of fashion. The notes are alive with a life, breath and purpose which only a superbly gifted musician can create.”

New York Times critic Allan Kozinn wrote in 2005: “One thing that separated Mr. Perle from so much of the serialist pack was that his music, whether serial or not, is driven by a deeply expressive and often lyrical impulse.”

Born to Russian-Jewish immigrants May 6, 1915, in Bayonne, N.J., Perle grew up on farms in Wisconsin and Indiana. He discovered his calling with his first musical experience when he was 7--hearing his aunt play Chopin’s Etude in F minor.

“It literally paralyzed me,” he said in a 1985 New York Times interview. “I was extraordinarily moved and acutely embarrassed at the same time, because there were other people in the room, and I could tell that nobody else was having the same sort of reaction I was.”

When he later told his parents that he wanted to compose, his mother said “that if that was what I wanted to do, I should do it.”

He earned a scholarship to study at DePaul University in Chicago, and while there discovered the piano score to Alban Berg’s “Lyric Suite” for string quartet. The event changed his musical life.

“I took it to the dormitory piano, and within the next five minutes my whole future direction as a composer was established,” Perle told the Chicago Tribune in 1990.

“It had seemed to me that it was no longer possible to write music that was really significant, because the traditional means of harmonic progression and structure no longer worked.” But Berg’s piece showed that “a new musical language was developing that would be as integral to the chromatic scale as the major/minor system had been to the diatonic scale.”

Perle went on to study with American composer Ernst Krenek in the 1940s and served as a chaplain’s assistant in the U.S. Army during World War II. He finished his music degree at New York University in 1956. He later taught at the University of Louisville, UC Davis, Queens College and the City University of New York, among other schools, and was composer-in-residence at the San Francisco Symphony from 1989 to 1991.

Berg remained absolutely central to his life. Granted access to the composer’s unpublished manuscript of the opera “Lulu” in 1963, Perle found that the third act was not an unfinished sketch -- as Berg’s publisher had claimed -- but was nearly three-fifths complete. Perle’s public protests about the misrepresentation eventually led to the completion of the third act by Friedrich Cerha and the performance of the entire work in 1979.

Perle also published a 1977 article revealing that Berg’s “Lyric Suite” had a secret subtext documenting a love affair with Hanna Fuchs-Robettin, the wife of a Prague industrialist and the sister of author Franz Werfel.

Perle’s publications about music long overshadowed his own achievements as a composer. His 1962 book, “Serial Composition and Atonality,” became the standard text on the music of Schoenberg, Berg and Webern and has been translated into many languages, including Chinese. He also wrote a definitive two-volume study of Berg’s operas.

Still, Perle developed his own manner of using the 12-tone method by applying traditional tonal principles to atonal technique. He explained his style in the 1977 book “Twelve-Tone Tonality.”

“I call my language ‘12-tone tonality,’ ” Perle told the Los Angeles Times in 1986. “That is not the same as serialism. The serial method is one way of using 12-tone material, but not the only way. Many composers of this century, including Bartok, used a 12-tone tonality in the same way that composers of the previous century used a seven-tone tonality.”

Although Perle composed assiduously, he was a ruthless critic of his own work. Many of his pieces he discarded or allowed to go out of print, especially those composed before 1970, when he felt he found his own voice.

“When people ask me how many string quartets I’ve written,” he told the New York Times in 1999, “I say four: No. 5, No. 7, No. 8 and No. 9.”

He wrote Adagio for String Orchestra for Carnegie Hall’s 100th anniversary and “Transcendental Modulations” for the New York Philharmonic’s 150th anniversary. Other works include Serenade for piano and chamber orchestra, “Songs of Praise and Lamentation,” Six Etudes for Piano, “Critical Moments 2,” “Brief Encounters” and “Triptych for Solo Violin and Piano.”

In his lifetime, Perle saw 12-tone music pass from being regarded as avant-garde to hopelessly academic.

“I’ve been an outsider in every way,” Perle told USA Today music critic David Patrick Stearns in 1991. “I’ve tried to do my work and put up with this situation, but it’s difficult.”

True to his convictions, Perle had little tolerance of the recent revival of conventional tonality.

“This so-called revival of tonality is a big joke, as far as I’m concerned,” he told the Chicago Tribune in 1986. “To play a simple cadential pattern for half an hour tells you that tonality, in a sense, is finished.”

“I don’t understand this business of trying to be accessible,” Perle later told National Public Radio. “When I write a piece, I write a piece that I like and I want to hear, and that I think will be fun to play. That’s all you have to think about.”

Perle was married three times. His first marriage, to Laura Slobe, ended in divorce. His second wife, Barbara Philips, died in 1978.

He is survived by his third wife, the former Shirley Gabis Rhoads; two children, Cathi Perle of Long Island and Annette Wolter of Sacramento; a step-daughter, Emma Rhoads of New York; two grandchildren, and three stepchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.