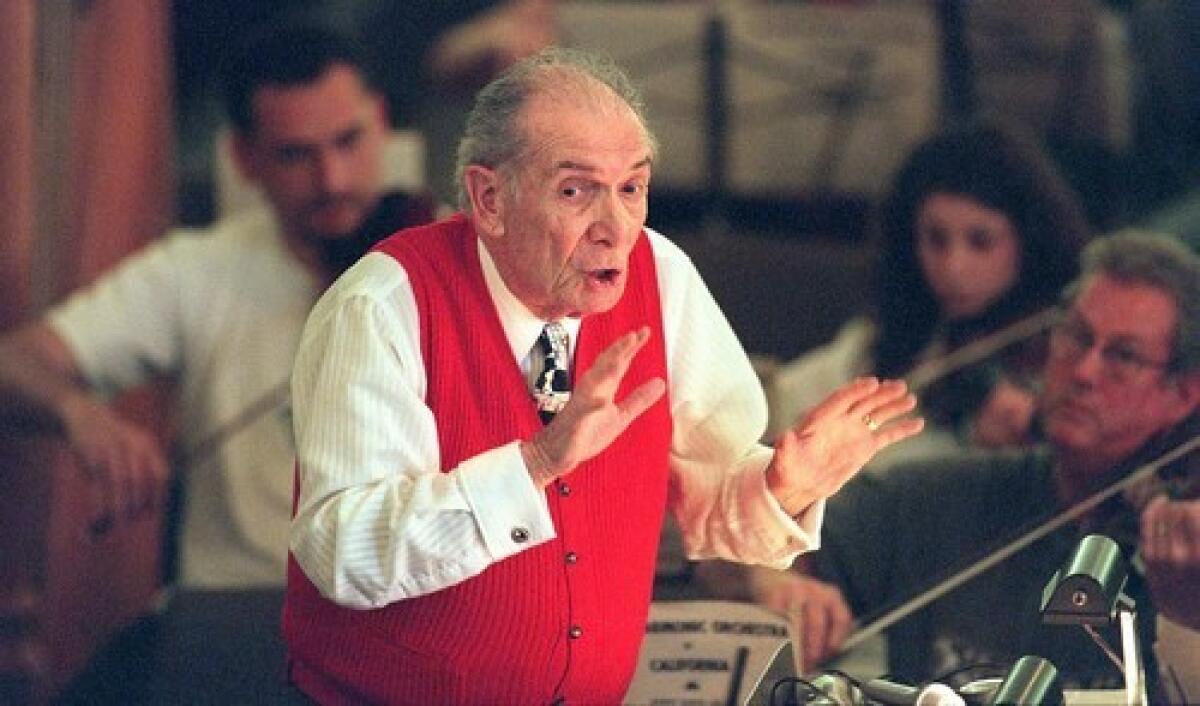

Ernst Katz dies at 95; founder and conductor of Jr. Philharmonic Orchestra

- Share via

Ernst Katz, who nurtured thousands of young musicians during 72 years as the founding conductor of the Jr. Philharmonic Orchestra of California, died of natural causes Tuesday at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, according to his nephew, Gary S. Greene. He was 95.

Katz formed what he originally called the Little Symphony in 1937 with four youths and built it into a 120-member orchestra that has played with such renowned guest artists as Isaac Stern, Jerome Kern, Meredith Willson, Richard Sherman, Jose Iturbi and Dimitri Tiomkin.

The 10,000 youths who have performed in the orchestra since its founding were charged no fees to participate. If they needed instruments, Katz lent them. If they couldn’t afford the tuxedos required for performances, Katz paid for them. He financed the organization almost entirely out of his own pocket, conducting free public concerts at such venues as the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion and Shrine Auditorium.

FOR THE RECORD

Ernst Katz obituary: The obituary of Ernst Katz, founder of the Jr. Philharmonic Orchestra of California, in Sunday’s California section referred to his late sister, Silvia Greene. She is still alive.

“He was like a musical Mother Teresa,” said entertainer Pat Boone, who performed at several concerts. “He had that kind of passion and personality to completely sacrifice his other interests to enrich and nurture the lives of young people through music.”

Katz was born in Detroit on April 14, 1914, and moved to Los Angeles with his Russian immigrant parents in 1922. His father founded the Golden Gate Hat and Cap Co., a Fairfax district business that caters to Hollywood, supplying such items as official Roy Rogers cowboy hats and the black fedoras worn by Michael Jackson.

As the only son, Katz was president of the company for many years, but his main occupation was music, starting at 12 when his parents bought him a piano. He spent the next dozen years on the concert circuit nationally.

The graduate of Garfield High School and Chapman College wanted to be a classical composer, but when the Depression hit, the only work he could find was ghostwriting movie tunes for Hollywood studios.

To supplement his income, he taught piano, which gave him the idea of forming a youth symphony to give young people hope during economically tough times. In early 1937, he started the orchestra with four boys and held rehearsals in his East Los Angeles home. As membership grew, he “moved out every stick of furniture from the living room, dining room and kitchen” and filled the space with folding chairs to seat his budding musicians.

After more than a year of rehearsals, the Little Symphony had its debut performance at Poppy Trail Villa, a community hall in East L.A. where Katz’s father stacked up wooden banquet tables to make a stage. Local music critics heaped such praise on the concert that the orchestra was invited to perform on a local radio program.

“Everyone said I was crazy” to launch a symphony during the Depression, Katz recalled in a 1996 Times interview. But he was determined to give youths “a chance to be heard.” That idea became the orchestra’s motto.

Although Katz had not set out to become a conductor, he embraced the role with contagious passion.

“When he came out on stage, he jumped up on the podium. He was very animated as a conductor,” recalled Dr. Walter B. Gaisford, a Utah surgeon who was concertmaster in the mid-1940s. “No one who played in that orchestra could forget Ernst Katz, how much fun it was to play in his orchestra and how much influence he had in their lives.”

Katz taught not only musicianship and the history of the compositions they learned to play but also lessons about individual responsibility, especially the importance of being on time to rehearsals.

If a player missed a cue or a note, “he slammed his baton,” said Luz Briseno, a professional musician who joined the orchestra in 1938 when he was a student at East L.A.’s Belvedere Junior High School, “and everyone would stop. Then he’d look you straight in the eye for a few seconds and make a complete 180-degree stare” that captured every performer’s attention. Then he directed his players to start over.

“He’d treat you like a grown-up,” Briseno said, adding, “I thank God that baton wasn’t a baseball bat!”

When the time came for the annual public concert, Katz polished a pair of black Florsheim shoes -- the same pair he wore to the first concert in 1938 -- and squeezed into them before stepping to the podium. A staunch patriot, he never started a performance without “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

He insisted on formal attire for the orchestra. At one concert in the 1970s a drummer who showed up without the requisite black socks hastily wrapped his ankles in black tape, thanks to his father, an electrician who kept a roll in his truck.

Greene said his uncle broke barriers for women, admitting girls to his orchestra from its inception. He also combined classical and popular music in the concerts, a practice that was taboo then but common today. “That’s where I learned ‘South Pacific’ and ‘Annie Get Your Gun,’ ” said Jorge Mester, conductor of the Pasadena Symphony, who joined Katz’s orchestra in 1949.

A highlight of the annual concerts was a segment Katz called “The Battle of the Batons,” in which celebrities with no conducting experience competed for the audience’s favor.

The first winner was actress Marjorie Main, best known for her movie portrayals of Ma Kettle. Others who vied for the distinction included Jimmy Durante, Jack Benny, Danny Thomas, June Lockhart, George Segal, Ed Asner, Richard Pryor, Chevy Chase and Weird Al Yankovic, the pop parodist, who conducted with one leg on the podium and one on his shoulder.

Katz’s authority was undiminished even in the last years, when his health began to decline. He turned over the podium to Greene but did not hesitate to speak up at rehearsals. “You were always conscious of his presence in the auditorium,” said Lockhart, a regular attendee at rehearsals. “He was absolutely inspirational.”

Running the orchestra was a family affair for the never-married Katz. He was assisted for many years by his late sister, Silvia Greene, whose children are keeping their uncle’s grand dream alive. In addition to Greene, Katz is survived by another nephew, Terry; a niece, Lori Green Gordon; and three grandnieces.

Katz might have set a record for time on the podium. Arturo Toscanini retired at 87, but Katz led the orchestra for 69 years, conducting his last concert in 2006 when he was 92.

“This is glory beyond expression,” he said as he prepared for his 60th anniversary as maestro. “You have no idea what it is to stand up there and feel the shimmer through my body going into my hands when I’m conducting this orchestra. I want them to know that life is worthwhile and if you give, you receive. We have to leave more than footprints in the sand when we leave this Earth, and that’s my ambition.”

A tribute concert is being planned. Memorial donations may be sent to Friends of the Jr. Philharmonic Orchestra Fund, care of California Community Foundation, 445 S. Figueroa St., Suite 3400, Los Angeles, CA 90071-1638.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.