Afghanistan bomb hunters learning to shed risky habits

In Kunduz, a U.S. team is training an Afghan unit to clear the roads. The Afghans have been known to shoot at the bombs or leave them after cutting the wires.

- Share via

Several weeks ago, Afghan army Capt. Mohammed Naweed came across a roadside bomb. As an engineer trained to find and remove explosives, he set about disabling the homemade device.

"It was booby-trapped with another bomb that exploded," Naweed recalled. The blast wounded him slightly in his legs.

"Next time," he said, "I'll follow the '5 and 25' rule."

That would be the rule taught by U.S. Army engineers: Check five meters around you, then 25 meters more to make sure the first bomb doesn't trigger a second one nearby.

Naweed's team is slowly learning the bomb-hunting trade here in the fertile farmlands and towering mountains of northern Afghanistan. Afghan soldiers have taken over most road-clearance duties from U.S. forces; they are now finding — or getting hit by — the roadside bombs planted here.

The bombs, known as improvised explosive devices, or IEDs, have been the single biggest killer of U.S. and coalition troops, responsible for about 60% of combat deaths and injuries in the 11-year-old war. Increasingly, Islamist insurgents are aiming the bombs at Afghan forces as the U.S. hands over combat responsibilities.

Over the last 15 months, nearly 3,500 Afghan soldiers and police officers have died in action, an estimated half of them because of roadside bombs, according to the ministries of defense and interior. The number of U.S. deaths over that period is about 300.

An American bomb-hunting team stationed in Kunduz, a platoon nicknamed the Predators, is essentially working itself out of a job by training Naweed's 81-man unit. It's a slow and often frustrating endeavor, the team says, but the Afghans are improving.

During Sgt. Bafuay's training exercise, the internal fan on his helmet stopped working. "If the U.S. guys don't fix it, it doesn't get fixed," another member of his Afghan unit said, shrugging. More photos

At first, it was "like trying to baby-sit an adult," said Spc. Uche Okoh, a U.S. Army mentor. Afghan soldiers have been known to dig at buried bombs with pickaxes, shoot them with assault rifles or just cut their wires and leave the bombs intact.

"Oh, we had lots of casualties," Naweed said. "Usually we couldn't find an IED until it exploded on us."

The Afghans have improved with U.S. training and equipment, said Sgt. Anthony Storm, who helps mentor Naweed's unit.

"Sometimes they do it the right way in training, then go back to their old ways out in the field," Storm said. "You know, just poking at the ground."

As Storm spoke, Afghan Sgt. Huseen Bafuay was drenched with sweat in a bulky, protective bomb disposal suit that made him look like a deep-sea diver. He was attempting to disable a dummy bomb buried on a dirt roadway as part of an exercise.

Another Afghan soldier had used a metal detector to locate the device, then screamed a warning. Bafuay, lying on his belly in the cumbersome suit, carefully scraped away dirt to reveal a yellow plastic jug filled with fake homemade explosives.

Usually we couldn’t find an IED until it exploded on us."— Afghan army Capt. Mohammed Naweed

The Afghan called for a wheeled robot named Talon. After fiddling with a joystick and computer controls linked to the Talon, an Afghan engineer sent the robot rolling over.

Once the dummy device was disarmed, several Afghan soldiers rigged a wire-and-pulley contraption to yank it loose. They tugged and jerked furiously. Nothing. Finally Naweed walked over and calmly hoisted the bomb out of the ground.

By this time, Bafuay had removed his bomb suit helmet. His face was crimson. The helmet fan had broken.

"If the U.S. guys don't fix it, it doesn't get fixed," Naweed said, shrugging. "I'm wondering who's going to fix all these things after the Americans leave."

Col. Nicholas Katers, commander of Joint Task Force Triple Nickel, a 5,000-strong U.S. engineering unit that includes route-clearance teams, worries that poor maintenance and repair skills will cost the Afghans dearly.

The U.S. military has supplied older versions of the robot and the electronic detection and jamming system known as Symphony, along with other devices. But to Afghan troops, Katers said, the Symphony system "is just an invisible magic box." Afghan soldiers, most of whom are illiterate, often don't know whether their systems are functioning properly or at all.

"You don't know it's not working till something blows up," he said.

In Kunduz, the Predators and two other U.S. platoons cover the largest area of any U.S. engineer unit in Afghanistan: a vast stretch of rugged landscape with more dirt tracks than pavement. For months, the engineers have bounced along rutted roads in mine-resistant vehicles equipped with high-tech sensors.

In a country saturated with roadside bombs, the three platoons of the 321st Engineer Company have searched 21,000 miles of roadways without a single IED casualty. Nationwide, the Triple Nickel's 50-some route-clearance teams have suffered just one death by an explosive device. (Other U.S. units that perform their own route clearances also have had deaths during that period.)

The company commander here, Maj. Patrick Freshwater, warned his men that the Taliban was planting more bombs with the summer fighting season underway. He told his men not to get complacent. Just three days later, an Afghan district police commander in Kunduz and his driver were killed by a bomb on a nearby road.

Sgt. Patrick Gorman, who operates the Talon robot, hasn't told his mother that he hunts bombs. Spc. Okoh hasn't told his wife.

"Telling my mom I look for bombs isn't really something I want to do," said Gorman, who was a University of Texas civil engineering student when he joined the platoon.

Okoh, 38, who served in the Nigerian army and ran a dental lab in Texas before joining the platoon, said his wife and three children didn't need the added stress.

"It's dangerous, and I don't want to scare anybody," Okoh said.

The mine-clearance convoy passes an Afghan farmer along a road. More photos

But the engineers also acknowledge that their searches of roadsides, farm fields and culverts for hours on end can be mind-numbing. They live to "BIP" — to "blow in place" uncovered bombs — but they've only found a single bomb.

"We love blowing things up," said Sgt. 1st Class Joshua Reece, 30, a fast-talking Arkansan. "But now we want the Afghans to be doing it."

On a recent patrol, two dozen U.S. soldiers wearing body armor rode in eight trucks protected by steel cages. The behemoths chugged along dusty roads, drawing baleful stares from Afghan men selling neatly stacked oranges and fly-specked goat and sheep carcasses hanging from hooks.

One vehicle had ground-penetrating radar panels that provided video images of bombs buried in roads. Another had "mine rollers," heavy devices that detonate pressure-plate bombs.

Some vehicles had gunners in the turrets. Others were mounted with a machine gun remotely fired by a soldier inside using a joystick and video screen. The system can track the source of enemy fire and accurately direct return fire.

On some missions, soldiers hand-launch a small drone called Puma, which provides a bird's eye view of the road ahead. "Gyro cams" mounted on vehicles scan the terrain, relaying images to video screens inside.

When on foot, the engineers use hand-held jammers that block radio signals used to detonate bombs. Some also wield hand-held bomb-detection devices.

An Afghan farmer waits as Spc. Uche Okoh uses a mine detector to sweep an area. More photos

On this mission, the men searched for bombs and trigger wires in a soggy wheat field. Gorman's boots and the pants of his fatigues were soaked as he sloshed around turtles basking in the sun, all the while scanning for signs of wires or bombs.

Okoh, loaded down with gear, slipped in the slick mud and fell face forward. His uniform was smeared with brown muck.

Okoh's tumble seemed the worst calamity of the nine-hour, 120-mile patrol. But when the soldiers returned to their base, they discovered a casualty: Gorman's Talon, a sort of miniature Mars rover equipped with cameras and probes.

The robot had been strapped inside a protective metal box lashed to the back of a vehicle. But it had taken several rough jolts and blows during the ride, and its metal arm snapped off.

Two weeks earlier, the Talon had been repaired after a similar bashing. Now Gorman would have to send it to another base for additional work.

The engineers climbed wearily from their vehicles at dusk, sweaty and exhausted. They'd have time for food, sleep and showers before the next morning's mission brought another long drive down dangerous roadways.

"A route is only clear until you leave," Maj. Freshwater said later that night. "Then you go back and clear it again."

Follow David Zucchino (@davidzucchino) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads (@latgreatreads) on Twitter

More great reads

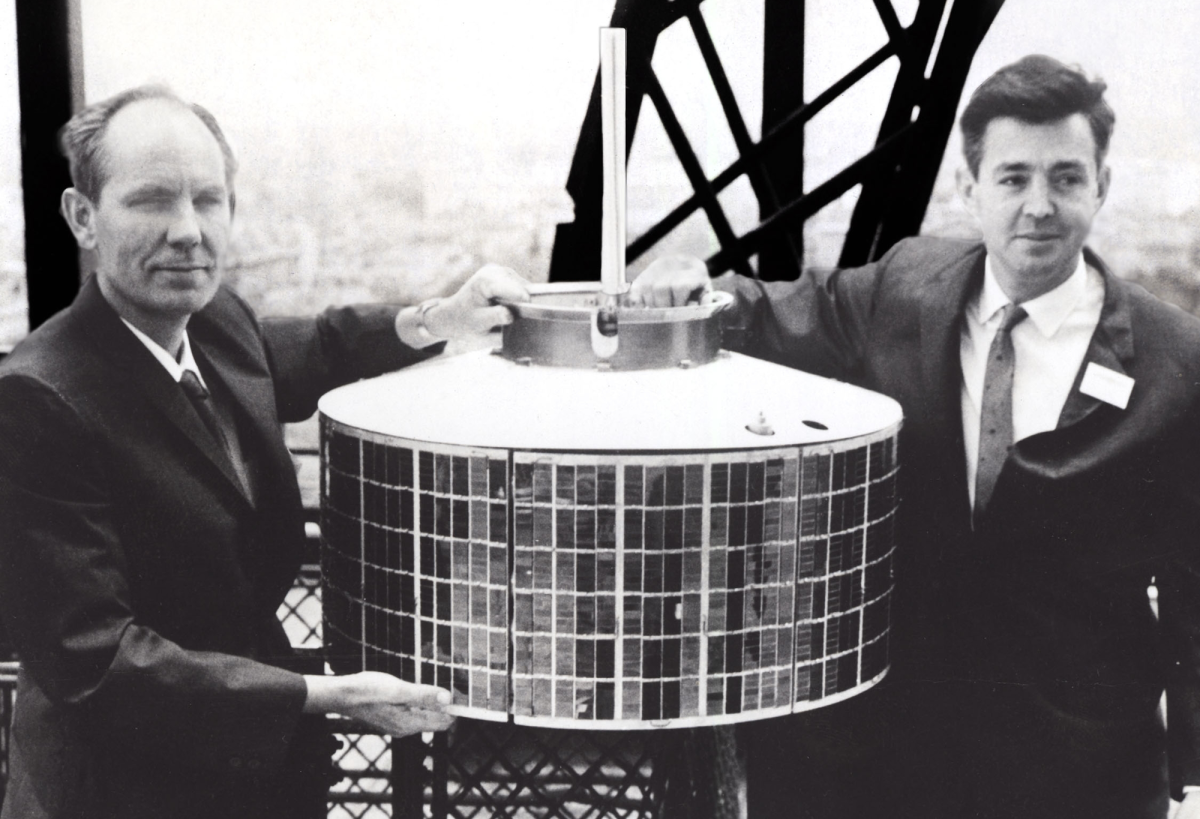

How a satellite called Syncom changed the world

We very quickly could feel that we had the world by the tail. We were way ahead of the curve."

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.