iPads in school: a toy or a tool?

- Share via

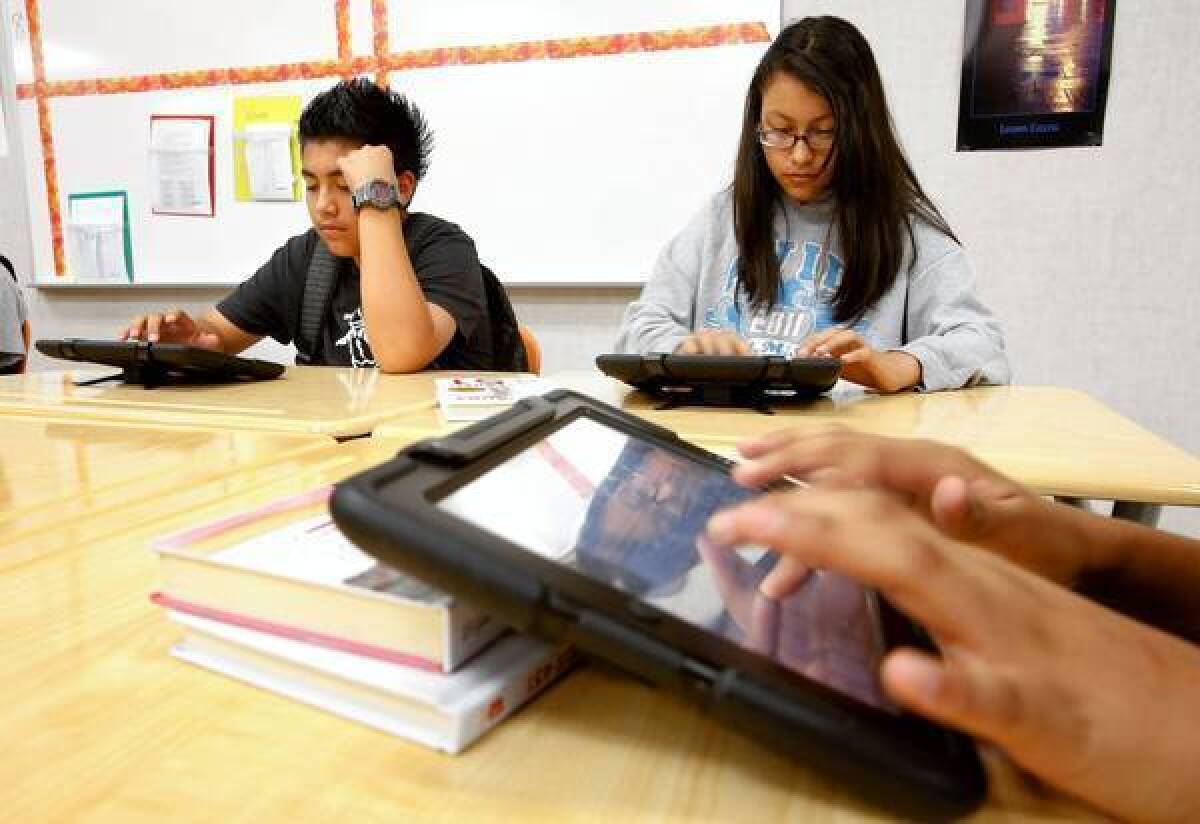

At Valley Academy of Arts and Sciences in Granada Hills, every student has an iPad.

That’s 1,200 iPads, and if L.A. Unified Supt. John Deasy can figure out how to pay for 660,000 more of them, every student in the district will have a tablet in the next few years.

A good idea?

“It’s magical,” declared a student at Valley Academy who loves his iPad.

Maybe. But I’ve got lots of questions.

Like many parents, my wife and I have tried to make sure our daughter reads real books and doesn’t get addicted to everything digital. And now her school district, which has laid off teachers and staff and eliminated programs because of budget problems, wants to spend several hundred million dollars on the latest electronic fad.

And LAUSD is not the only district racing into the future while struggling to fix leaky roofs and broken toilets. As Deasy argues, students are supposed to begin taking standardized tests on electronic devices in the 2014-15 school year as part of a new curriculum. And he said it would be irresponsible not to prepare students for an increasingly digital economy.

But Stanford University education professor Larry Cuban has lots of reservations.

“There is still no evidence that iPads will increase student achievement at all. It’s not the hardware, it’s the software, and no studies have been done on the software apps in use, so no one knows,” said Cuban, who suggested the money might be better spent on training and recruiting teachers. “I’ve seen students with iPads and the novelty is there and the engagement is there, but it’s not clear that novelty and engagement will lead to increased academic achievement.”

It should be noted, as well, that people with ties to tech companies were among the major donors to a political action committee that supports Deasy-friendly school board candidates. As reported by my colleague Howard Blume, $250,000 came from the parent corporation of a company that sells tablet computers designed for schools. Another $200,000 came from a group headed by the widow of Apple founder Steve Jobs.

And Deasy appears in a promotional video for Apple in which he says tablets are “phenomenally going to change the landscape of education.”

Deasy told me he received no money for being in the ad and that he has no role in choosing what companies the district does business with. Regardless, he’d be better off not serving as a pitchman for any product.

Given the advent of test-taking by computer, a teacher who’s a friend of mine worried that this is “another sign of how tests are taking priority … over everything,” and she wondered if this is part of a plan to facilitate teacher assessment. She added: “I think the paper and pencil version of tests works just fine,” and she complained that teachers haven’t been consulted on whether tablets are useful teaching aids or potential distractions.

Other skeptics have raised questions about maintenance costs and equipping schools with WiFi — not to mention the tendency of kids to drop things. And there have been disputes about whether voter-approved bond money could be used for tablets.

But having said all that, what I saw at Valley Academy — the first of about a dozen schools to get iPads in a $50-million pilot program — was impressive. And the principal, Debra McIntyre-Sciarrino, had glowing reviews and noted that the iPads are great equalizers, because many students come from homes where electronic tablets are beyond the family budget.

The impact “was immediate and dramatic,” she said. The tablets helped create “a dynamic learning environment” in which students and teachers were prompting each other. And the distraction feared by some teachers can be mitigated with locks that prevent students from using anything other than the assigned program.

Let it be noted that the school’s Internet service crashed on the day of my visit and tech help had to be summoned. Still, I saw some impressive work. In a geometry class, students Jose Cruz and Brandon Zulueta showed me a project they had just completed. Using old-fashioned paper, they made geometric origami figures, then used an iPad program to produce a stop-animation video in which a harpoon chased a whale. The animation was used to illustrate a story they’d written about a drama on the high seas.

Their teacher, James Emley, told me that in his physics class, students used iPads to design rockets and test them in a virtual wind tunnel.

English teacher Jenn Wolfe said grades improved when students were allowed to take the iPads home rather than lug textbooks. But district officials determined that restrictions on the bond money that purchased the iPads required that they stay at school.

One of her students, Meagan Toumayn, showed me a multimedia project she did on cruelty to animals. Sarah Gonzalez showed me a digital index of her assignments, notes and reports on the classic novel “To Kill a Mockingbird.” When the honors class read “Romeo and Juliet,” they were able to hear audio pronunciations of British words they were unfamiliar with.

“This is not a teacher and it’s not a student, either. It’s a tool,” Wolfe said of the tablet.

“We can’t go backwards,” she said. “We’re preparing kids for jobs we don’t even know about yet.”

If for some of us the jury is still out on iPads, that’s not the case at Valley Academy. I asked Wolfe’s 36 students if anyone wanted to go back to doing things the old-fashioned way.

Not a single hand went up.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.