The stars align for kabbalah

- Share via

Second of two parts

When Philip Berg decided in the early 1970s to teach kabbalah to the masses, he predicted that orthodox rabbis would stone him and his wife, Karen. For a long time, that seemed a pompous overstatement. Few people had even heard of the kabbalah school they ran out of their living room in Jerusalem and later in Queens.

But Philip knew that revealing the secrets of the Torah to any Jew who wanted to learn them -- spiritual teachings once open only to elite rabbinical scholars -- would be controversial. It also proved wildly popular.

Two decades later, the Kabbalah Centre had become an empire with branches in major cities, a publishing arm and scores of passionate young volunteers. Then in March 1990, the center caught the attention of a council of rabbis in Toronto. They didn’t stone the Bergs, but they publicly disputed the validity of Philip’s teachings of ancient Jewish mysticism and took exception to the center’s aggressive fundraising.

“We have become aware of a group of young men promulgating the sale of so-called kabbalistic literature and of their establishment of classes in this topic,” the rabbis wrote to the city’s orthodox community. “We categorically state that the group known as the Centre for Kabbalah Research is not approved nor endorsed by the undersigned rabbis.”

The letter was circulated among Jewish groups around the world. In Jewish enclaves where the center had long gone door-to-door soliciting donations, there was sudden hostility. People ordered members off their front porches and sometimes out of their neighborhoods. The repercussions reached the Bergs’ two sons, who were students at an orthodox yeshiva in New York. Their teachers told them to abandon their father, according to a former member who at the time was close to the family.

The rabbis’ denunciation might have been fatal to a more traditional Jewish organization. But the Kabbalah Centre taught that the closer a person drew to the light -- God -- the more the forces of darkness would target him. Followers saw the criticism as proof that the Bergs were on the right spiritual path. They hailed them as prophets.

Members of the chevre, the center’s religious order, discussed the intense level of spiritual development one would need just to be Karen’s assistant and lined up to eat Philip’s leftovers as a way to show their devotion, former members said. The center’s synagogues around the world had special chairs for the Bergs’ exclusive use, even though they might visit only once a year.

It became standard practice to address the Bergs in the third person. “Does Karen want water?” followers would ask her. “How is the rav today?” they would inquire of Philip.

A large painting at the Toronto branch showed Philip in what struck one visitor as a classic Christian pose: Jesus leaning against a rock.

“It was the very same picture, except it was the rav’s face,” recalled Dorothy Clark, whose husband, Kenneth, helped Philip write books that sought to popularize kabbalah.

An inner circle of very wealthy donors -- the “close people” as they were known at the center -- gave hundreds of thousands and sometimes millions of dollars in tax-deductible tithes and donations. Big donors were rewarded with seats at the Bergs’ table at Sabbath meal, invitations to intimate prayer services and personal conversations. Those who grumbled were chastised by officials or other students.

“When you brought up something about the family, they would tell you it clearly shows you have an opening in your consciousness for Satan,” said a former longtime member who grew disillusioned and left the center but did not want to be named because relatives are still members. “Clearly you are not doing enough to get the light.”

Adored inside their organization, the Bergs continued to be vilified outside. Rabbis in Israel, Philadelphia and Queens condemned them publicly. At a religious conference in Johannesburg, South Africa, an orthodox rabbi gave a speech criticizing the center’s practices and Philip’s “scandalous” personal life, an allusion to the breakup of his first marriage. The center responded with a defamation suit, which it later dropped.

L.A. headquarters

The Bergs were spending more time in Los Angeles, running the center from a converted 100-year-old Spanish-style church on Robertson Boulevard. The location, which became the center’s world headquarters in 1998, was near the heart of the city’s orthodox community, but more significant was its proximity to Westside neighborhoods the entertainment industry calls home.

The first celebrity drawn to the Kabbalah Centre was Sandra Bernhard, who began studying in 1995. Bernhard was a raunchy stand-up comic who’d posed nude for Playboy. She dove into kabbalah classes with a charismatic Israeli teacher, Eitan Yardeni. She was effusive in the media about kabbalah, which she said had eliminated “at least 80% of the chaos in my life.” In her Hollywood circle, she was a one-woman marketing campaign for Yardeni and the center.

“Sandra told me that I would love him, and that he was for real, and righteous,” Roseanne Barr wrote in her memoir “Roseannearchy.” Both comedians are Jewish, but other people Bernhard recruited were not.

In the Bergs’ decades of challenging tradition, the center had remained fundamentally Jewish. The conflict with the orthodox establishment had always turned on whether kabbalah study was permissible for certain Jews -- women and men without yeshiva training. Gentiles were never even a consideration, and were a rare and generally unwelcome presence, according to former members. Gentiles at Sabbath services were expected to stay in the back and not participate.

“We had to be careful to avoid contamination,” said former student Michel Obadia, recalling the concern over a “non-Jewish eye” witnessing the blessing of wine.

That changed with the arrival of Bernhard’s diverse circle. Gentiles flocked to an introductory course she arranged in Manhattan.

“Non-Jews are welcome at this class,” the New York Times declared in 1996 in one of several news stories that saw a hot, new trend in the scene of a yarmulke-wearing teacher from the center instructing a crowd of actors, models and designers.

It was difficult for some former disciples to square the ecumenical approach with the Kabbalah Centre they had known.

Jeremy Langford, an early follower who left the center in 1984 over concerns about its authenticity, said reports about gentile celebrities attending classes confirmed his belief that the Bergs were teaching “pop, light, quasi New Age, ersatz kabbalah.”

Nothing garnered bigger headlines for the center than the arrival of Madonna. She enrolled at the L.A. center in 1996 at Bernhard’s suggestion.

“It didn’t really matter that I was, you know, raised Catholic or I wasn’t Jewish and I felt very comfortable and I liked being anonymous in a classroom environment,” she told television personality Larry King in 1999.

To the surprise of her detractors, Madonna stuck with her studies. She attended Sabbath services, had one-on-one study sessions with Yardeni, enrolled her daughter in the center’s Sunday school and chose a Hebrew name, Esther.

The Kabbalah Centre suddenly had cachet among the rich and famous, and through them entree to a wider audience. Yardeni was at ease with big names and egos, and the Bergs tapped him as their Hollywood emissary. He had once worked as a door-to-door chevre and had a humility and directness that the powerful and well-connected found refreshing.

“I thought Eitan was very, very bright and a very good spiritual teacher,” said talent manager and producer Sandy Gallin, who first heard Yardeni speak at Barr’s home. He said one-on-one tutoring with Yardeni taught him “to take the high road and to understand there is a greater power than you.”

The list of celebrities attracted to the center grew to include Elizabeth Taylor, Gwyneth Paltrow, Britney Spears and Paris Hilton.

Yardeni held exclusive sessions at Westside mansions. Producer Christine Peters hosted one that drew entertainment figures that included her then-boyfriend, Viacom Executive Chairman Sumner Redstone.

“He was so wonderful,” said Cindra Ladd, wife of former 20th Century Fox President Alan Ladd Jr., recalling classes she attended at a Pacific Palisades home. She said Yardeni would begin by reading from the Zohar and the Torah, the first five books of the Bible, in Hebrew and English. He would relate stories about Moses and other biblical figures to daily life. Topics included how to achieve lasting fulfillment, how to transform oneself “in the light of God” and how to refrain from gossip.

“That was the hardest one for everyone,” Ladd joked.

Yardeni’s teachings about finding meaning beyond the material had a special appeal to those in her circle, said Ladd, who was raised a Mormon.

“A lot of times people in this town who are very successful are left with a feeling of ‘Is this all there is?’” she said.

Tax exemption

The heightened profile of kabbalah meant enormous growth, but precisely how much is difficult to say. The parent organization, Kabbalah Centre International, was granted tax-exempt status as a church in 1999 and stopped filing returns.

The center’s assets grew from $20 million in 1998, the year after Madonna went public with her ties to kabbalah, to more than $260 million by 2009, according to the resume of a former chief financial officer and tax returns the center and affiliated organizations filed before becoming exempt.

The center’s revenue sources include fees for classes and sales of merchandise such as candles, red-string bracelets that the center says will ward off evil, and bottled water long touted as having healing powers.

Soliciting donations remained a focus of the Bergs and other ranking leaders. Major donors to the center or its affiliated nonprofits include Madonna, whose foundation has reported giving more than $10 million, and fashion designer Donna Karan, whose foundation has reported giving at least $2 million.

A prominent filmmaker said that after a few lessons with Yardeni, he received an unannounced visit from another official. You are a rich man and you should be giving millions, the filmmaker recalled being told. He said he ordered the man off his property. The filmmaker asked not to be named for fear of offending industry colleagues still involved with the center.

There also was pressure on less well-off students. George Cabral, a welder in Melbourne, Australia, who participated in a class on Skype, said that when he cut his $100 weekly tithe in half to pay bills, his teacher was furious. The man told him to write “I’m in debt to the cosmos” on a piece of paper each day. Instead, he quit.

Some requests came directly from the Bergs, as in the case of a wealthy Calabasas family who turned to the center after their matriarch was found to have cancer.

Samuel Raoof, a former Kabbalah Centre student, said his parents were invited to join the Bergs at their table after Sabbath services in 2000 or 2001. Raoof, chief executive of a skin-care company, said his parents returned to their own table and told him what happened: Philip had urged them to commission a Torah for the center to “help cure” his mother’s cancer.

Philip did not mention money, Raoof said his parents told him. But later, the couple’s teacher visited the father at his office, repeated the claim about the Torah’s curative powers and requested a $100,000 donation to have a scribe write the scrolls, Raoof said.

Raoof said his father, a physician, was infuriated and refused the request. Raoof said the teacher, who had grown close to his mother, then went to a clinic where she was receiving chemotherapy and persuaded her to give about half the amount.

Raoof said his father eventually paid the rest, hoping the Torah dedication ceremony might provide his wife some final joy with family and friends. Month after month, the family was told the Torah wasn’t ready, according to Raoof.

After his mother died in 2004, Raoof said, the family was told by letter that its donations had gone to the center’s general fund, not for a Torah.

The center eventually agreed to create a Torah, Raoof said. The family ultimately rejected the offer and asked for their money back, which the center refused, he said.

Raoof showed The Times copies of four canceled checks from late 2003 and early 2004, drawn on his parents’ account and made out to the Kabbalah Centre, totaling $107,000. The word “Torah” appears in the memo field on three of the checks.

The elder Raoof declined to discuss the matter but confirmed his son’s account.

Change of lifestyle

How much of the center’s money made its way to the Bergs is unknown.

Their lifestyle changed markedly after the celebrity influx, however. Billy Phillips, a longtime family friend, said the Bergs had previously lived like paupers with no privacy in simple accommodations at the Robertson Boulevard center, which followers considered beneath their status.

“People had been begging to give them houses,” Phillips said.

In the mid-2000s, the Kabbalah Centre bought three houses side by side in Beverly Hills for the couple and their two sons. The homes on South Almont Drive are relatively modest by Beverly Hills standards, with appraised values of up to $1.8 million each.

“They are far from being mansions,” said Naftali Gruberger, a Brooklyn cabinetmaker and one of Philip’s sons from his first marriage. “My house is bigger than that.”

Birthday parties for Philip were elaborate affairs, including one in 2003 at a Hollywood Hills mansion where Michael Buble and Madonna serenaded the guest of honor.

Donors lined up to cover the cost of the parties and other luxuries, demonstrations of loyalty that assured a place in the inner circle, former members said. Gifts included private plane rides, jewelry and trips to Europe and Mexico, they said. Supporters defend such gifts as expressions of gratitude.

“If there’s a really rich student, very wealthy, and he wants to cover someone’s car lease and that’s the way he gives, are you going to insult him and not take the gift?” Phillips said.

Arthur “Archie” Falkenstein, a Toronto volunteer who worked closely with the Bergs, said, “Everything they have is donated or bought for them.

“Show me one spiritual leader in the world who had not been given gifts,” he said.

Some former associates say the Bergs made gambling trips to Las Vegas, where the center has a branch, and that the couple sometimes stayed at Caesars Palace and other casino-hotels on the Strip. They were frequent enough players to receive complimentary meals, rooms and limousine rides from the airport, according to three people who said they had gambled in Las Vegas with the Bergs.

One of the three recalled an occasion when Karen played craps at Caesars with a stack of $100 chips while Philip watched “like a bystander.”

A second former member described casino trips when both Bergs played blackjack at the $100 table. The man said IRS agents investigating the center’s finances had recently questioned him about the Bergs’ gambling and that he had given them the same account he gave The Times.

The Bergs were staying at the Bellagio in September 2004 when Philip suffered a stroke, said people who were in Las Vegas with them. It was a devastating blow for followers who had been taught that the truly spiritual could conquer illness. The community rallied with round-the-clock Zohar readings outside his hospital room.

Philip, who began using a wheelchair and had difficulty communicating, could no longer lead the center.

Succession debate

The issue of a successor was debated at a 2007 meeting of the chevre in Boca Raton, Fla. The obvious candidates were the Bergs’ sons: Yehuda, an outgoing jokester who favored baseball caps over yarmulkes and interrupted spiritual lessons to announce the Lakers score, or his younger brother, Michael, an introverted scholar who had a close friendship with Madonna.

The sons, both in their 30s, were well liked, but some followers did not see them as mature enough to lead. Karen was urged not to step aside, said two people who attended the meeting. She and her sons are co-directors of the center, but Karen, 68, is chief executive of the parent organization, Kabbalah Centre International, and is identified as “spiritual leader.”

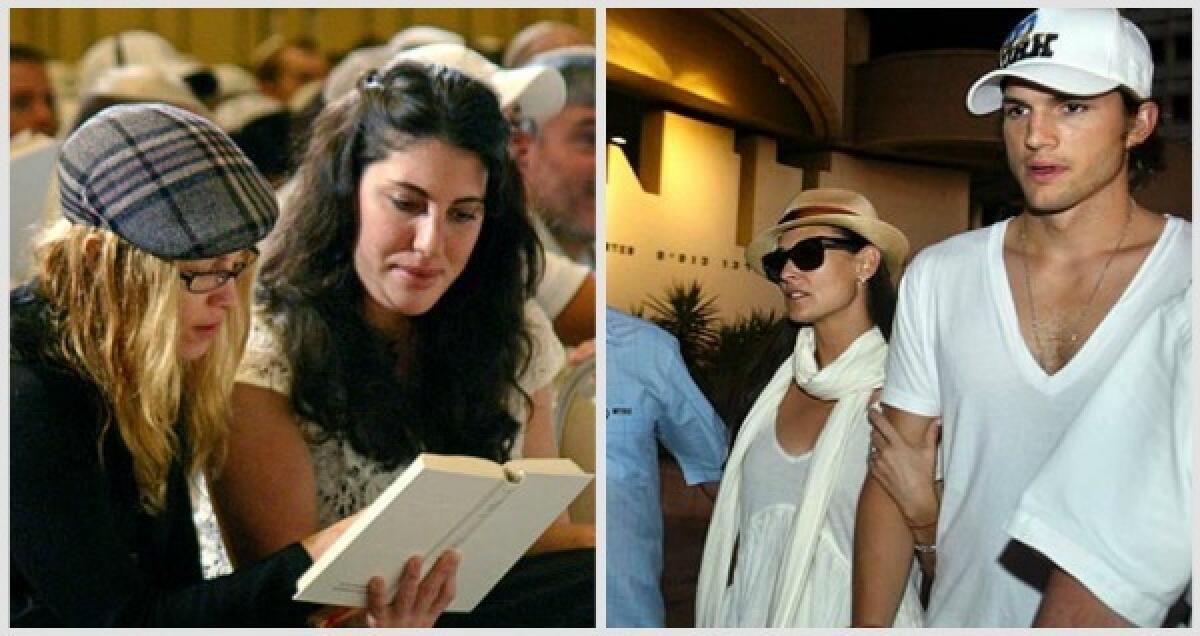

As the center continued to court Hollywood -- Yardeni officiated at the wedding of Ashton Kutcher and Demi Moore in 2005, Yehuda Berg threw a paparazzi-mobbed book party at Kitson’s flagship store on Robertson -- it seemed to de-emphasize Judaism more than ever.

“You don’t have to stop being Catholic to study kabbalah. You can be both,” a member from Miami said in a marketing video that claimed the center’s teachings were “known to Jesus” and applicable to “those of no faith.”

Some longtime members became upset about what they perceived as Madonna’s outsize influence. After the singer adopted a son from Malawi, she and Michael Berg co-founded a children’s charity with offices at the center. The cause seemed worthy, but difficult for some to reconcile with the center’s teaching that donations should be confined to efforts that spread the Zohar.

“Everything changed once Madonna began to study,” said Barr, the comedian. “Madonna had great intentions, and has done a lot of good things in the world, but her fame was so immense that there was no way that God or kabbalah or the rav or Karen Berg or heaven and Earth could remain the same in the face of it.”

After Philip’s stroke, a number of major donors and celebrities, including Barr and Bernhard, left the center. Norton Cher, a New York apparel manufacturer who said he donated about $400,000 over a decade, said he and his wife disliked what they saw as Karen’s all-business approach.

“It just got too commercial,” he said. “The people there just wanted more and more and more. We kind of decided we don’t need a broker: When we want to talk to God, we’ll do it ourselves.”

The disaffection spread. The empire the Bergs had built over four decades suddenly seemed vulnerable.

Shaul Youdkevitch and his wife, Osnat, high-ranking chevre who had been with the center since the 1980s, departed in 2008. “The magic was gone; the love turned to confusion, cynicism and bitterness,” Youdkevitch wrote in a blog post addressed to “dear friends” at the center.

He said that after complaining that Karen had too much power, “we were presented with an ultimatum to have us agree that Karen Berg possessed Ru’ah HaKodesh -- Holy Spirit (total obedience to every decision of hers) or that we could no longer work within the Kabbalah Centre.”

“Biblical law has never allowed any human being to be above the law and above constructive criticism,” Youdkevitch wrote.

The dispute became ugly. A lawyer for the couple sent a seven-page letter to Karen detailing the money they had brought to the center and demanding $7 million for their three decades of unpaid work. The center had 72 hours to respond, the lawyer wrote, or the Youdkevitches would ask authorities to investigate its finances.

The center called the couple’s bluff and sued them, alleging that a kabbalah group the Youdkevitches had started nearby was unfairly competing with the center and using its trademarks and trade secrets. After months of legal wrangling, the center dropped the suit.

Many longtime “close people” who had provided donations and companionship were gone. Increasingly, Karen leaned on Moshe “Muki” Oppenheimer, an Israeli management consultant. Oppenheimer’s forceful presence, at a time when Philip was less visible, became a topic of conversation.

Rumors of an affair between the two became public in June 2010 when the New York Post’s Page Six gossip column published a denial from a Kabbalah Centre spokesman. The paper called the allegations “a false story” and quoted a center insider who blamed a disgruntled ex-member for trying to create “a scandal that could destroy the Kabbalah organization.”

The gossip was beaten back, but a greater threat to the organization was about to emerge.

Allegation of fraud

In August 2010, Nicholas Vakkur complained that he was fired as chief financial officer after less than three months because he had uncovered income tax fraud at the center.

“This is very serious business,” Vakkur wrote in an email that circulated among center officials. “I have little choice but to cooperate with the IRS and bring down the entire Kabbalah Centre.”

Months later, the criminal division of the IRS launched its investigation, focused in part on whether the Bergs enriched themselves with members’ donations. Prosecutors subpoenaed financial records from the center and two affiliated charities with links to Madonna.

Among those the IRS agents interviewed were former employees and ex-members. Those questioned in recent months said investigators possessed an impressive knowledge of the Bergs’ world, right down to the name of a casino host who arranged free hotel rooms for the couple in Las Vegas.

Celebrity followers have gone silent. Less famous adherents continue to defend the Bergs.

“They have spent their whole lives spreading kabbalah and trying to help people,” said Falkenstein, the Toronto volunteer.

Phillips, the longtime friend who participates in a weekly scripture study that the 82-year-old Philip attends, said it is inconceivable that the family has done anything wrong.

“When it comes to honesty, integrity,” he said, the Bergs are “infallible -- or they are not kabbalists and there is no Torah.”

Times staff writer Richard Verrier contributed to this report.

Kabbalah Centre founders’ statement

Phillip and Karen Berg, founders of the Kabbalah Centre, declined to be interviewed for this report and instead issued this statement:

“The Kabbalah Centre is a nonprofit organization leading the way in making Kabbalah understandable and relevant in everyday life. Our funds are used in the research and development of new methods to make Kabbalah accessible and understandable.

“The Kabbalah Centre has received subpoenas from the government concerning tax-related issues. The Centre intends to work closely with the IRS and the government, and is in the process of providing responsive information to the subpoenas.

“The Centre is disappointed that the recent press regarding the Centre and this investigation is being fueled by rumors spread by a few disgruntled former students and former employees with personal agendas. The Centre is confident that the investigation will show that the Centre has and continues to serve its mission and act in furtherance of the wisdom and teaching of Kabbalah.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.