Could an Africa-sized Ebola outbreak happen in U.S.? Officials say no

- Share via

More than 3,000 people are believed to have died in West Africa during the worst outbreak ever of Ebola. But public health officials are confident that the United States will not confront a similar crisis and point to the nation’s modern medical and public health system, past experience and the nature of the disease for their optimism.

“I have no doubt that we’ll stop this in its tracks in the U.S.,” Dr. Tom Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said at a news conference Tuesday, announcing the first diagnosed case of Ebola in the United States. “The bottom line here is that I have no doubt that we will control this importation, or this case, of Ebola so that it does not spread widely in this country.”

Frieden’s words were designed to reassure a public whose movie, television and reading fare for generations has included a killer disease – usually coming out of Africa – that spreads seemingly without end until heroic doctors fight a difficult battle that is narrowly won at the end, saving humanity.

The reality of the current outbreak is far more prosaic.

In a world of countries bound tightly by travel and other ties, the fear of contagion has been an ever-present concern and as a result, public health officials routinely train for how to handle such emergencies. In the last decade alone, the United States had five imported cases of viral hemorrhagic fever diseases similar to Ebola and none resulted in mass outbreaks, according to the CDC.

By early November, the World Health Organization warned that this year’s Ebola outbreak could exceed 20,000 cases and the CDC suggested that the extreme worst-case scenario was 1.4 million cases by January if nothing further was done. In addition to stepped up aid for Africa, American hospitals were put on high alert. There have been at least four reports of possible Ebola patients, including in New York and Florida, but all tested negative for the virus.

Health officials expected some cases to emerge in the U.S. Dallas was simply the place that won the unfortunate lottery. But officials had already been taking precautions.

“We have had a plan in place for some time now for a patient presenting with possible Ebola,” said Dr. Edward Goodman, an epidemiologist at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital, where the infected man is being treated. “Ironically, we had a meeting the week before of all the stakeholders who might be involved. We were well prepared to care for this patient.”

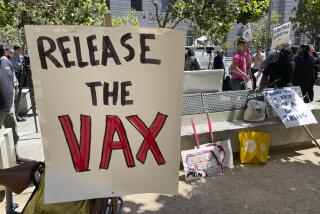

There is no treatment for Ebola, nor is there an approved vaccine. Treatment often involves keeping the patient hydrated, trying to bring down the fever and using drugs to prevent associated infections while keeping the patient comfortable during the painful period that the fever runs its course. In the Third World, where the healthcare system is poor, the mortality rate from Ebola can reach above 70%.

In the United States, three of four aid workers who contracted the disease in Africa have successfully been treated and released. They received different experimental treatments, including the drugs ZMapp and TKM-Ebola. The fourth is still hospitalized, but reports say he is recovering.

In addition to a modern medical system, communication and transportation systems in the United States allow people who fear they are infected to contact authorities and get to help far more quickly than in the Third World. Those systems also make tracing the infected person’s contacts easier so that, if needed, contacts can be quickly placed in isolation for observation. There was also an upsurge in public health spending and preparation after bio-terrorism threats more than a decade ago.

The United States health system has experience dealing with infectious diseases and has a tradition of quarantine and contact tracing in times of emergency. For example, in the early 20th century, there was Typhoid Mary (yes, she was a real person). Born in Ireland, Mary Mallon was a cook who was an asymptomatic carrier of the pathogen associated with typhoid, a serious public health concern. She was believed to have infected more than 50 people, three of whom died. She spent much of her life in quarantine. Given Ebola’s time span, such extreme measures are unneeded.

More recently there was the outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, or SARS. First surfacing in southern China, the virus infected at least 8,000 people and caused 775 deaths between November 2002 and July 2003. The outbreak hit many countries including Canada before it seemed to burn itself out.

But Ebola spreads differently than typhoid or SARS.

In order to be infected with Ebola, the person has to have direct contact with the bodily fluids from someone who already shows symptoms. For example, the other passengers on the plane from Liberia to Dallas are not in danger of contracting Ebola because the patient had no symptoms when boarding the craft. If he had symptoms he wouldn’t have been allowed to fly to Texas.

Like Ebola, SARS was also spread by contact with infectious material, including bodily fluids. But SARS most likely was also spread through the air, prompting a run on high-quality face masks in China and elsewhere.

There has been no reported case of Ebola being spread by breathing.

Follow @latimesmuskal for national news.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.