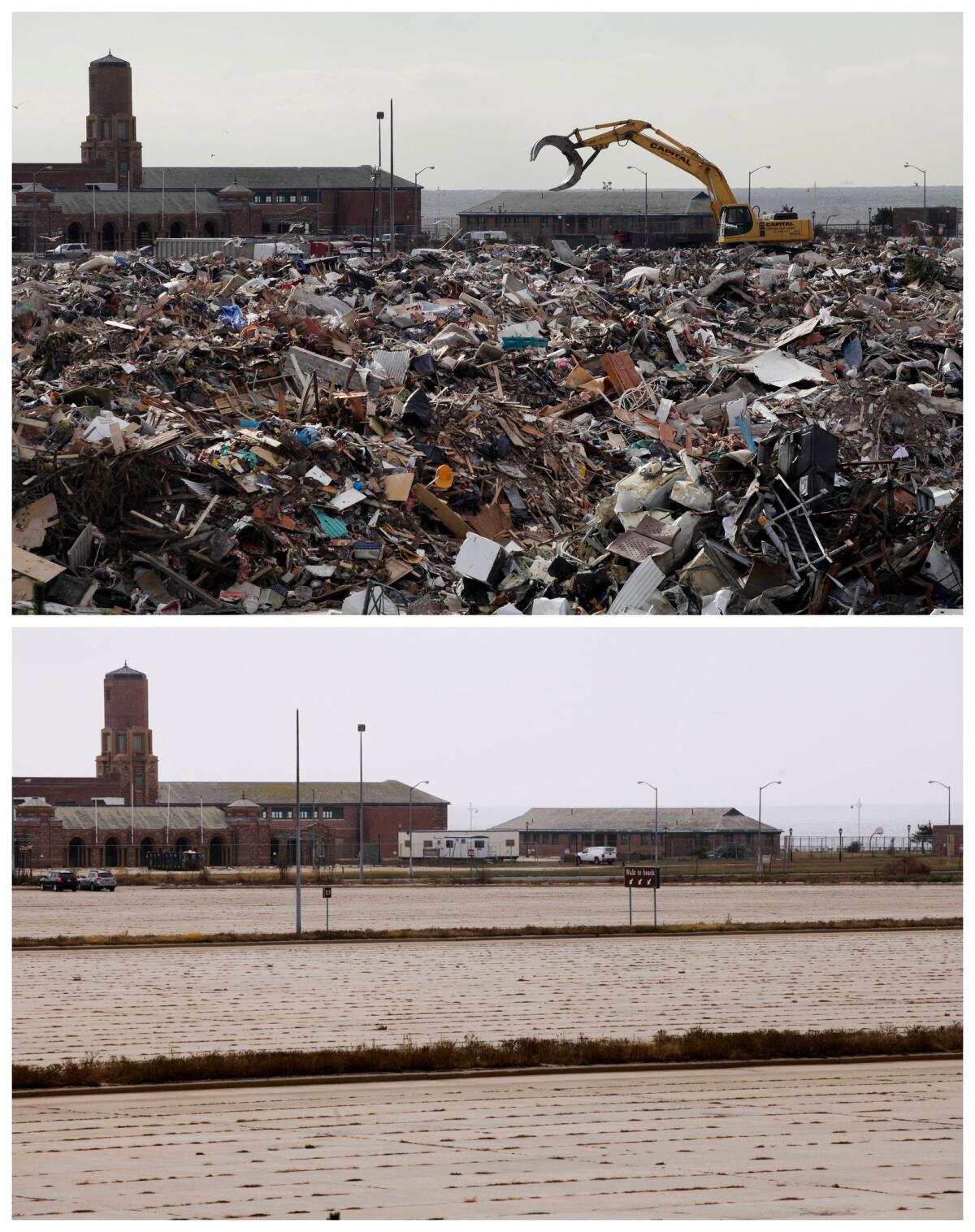

Superstorm Sandy: The devastation, loss and recovery one year later

- Share via

Ellis Island, which greeted millions of immigrants to the United States, reopened its museum doors on Monday, a year after the aptly named Superstorm Sandy tore through much of the eastern half of the United States, killing scores of people and destroying tens of billions of dollars in property.

More than a million documents, photographs and other artifacts were moved from Ellis Island to safety in Maryland after the storm roared through, creating swells as high as 8 feet that damaged what was the point of entry for immigrants coming mainly from Europe. The electrical systems on the island also failed.

PHOTOS: Before-and-after photos of Sandy devastation

In many ways, Ellis Island is a symbol of the first anniversary of Superstorm Sandy---hopeful because the museum is reopened. But it is also an expression of what is still to be done. Many documents, photographs and other artifacts, moved to safety after the storm, have yet to be put back on exhibition.

Here is look at the massive effect of the storm one year later:

THE SCOPE: The storm, the deadliest and most destructive of the 2012 hurricane season, ripped a hole through the psyches and infrastructure of the Eastern Seaboard when it made landfall on Oct. 29 and struck hard in New Jersey, metropolitan New York and moved through New England.

At least 117 people died in the United States, millions were without power for days and in some areas, weeks. Gasoline shortages crunched rescue efforts, disrupted the supply of necessities such as food and water and wreaked havoc with transportation and communications systems. Corrosive floodwaters surged through tunnels and subways.

The federal government has already spent more than $14 billion in assistance to New York and New Jersey alone. At least $250 million has been spent on Sandy-related repair and recovery projects for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority region, which runs New York subways and buses.

Utilities have repaired the damaged transmission wires and generators. Private funds have helped rebuild disaster areas from New Jersey’s tourism boardwalks and beach communities to some of the estimated 300,000 homes that were destroyed or damaged.

THE METEOROLOGY: Hurricane Sandy formed Oct. 22, 2012, growing to a Category 3 storm as it worked its way through the Caribbean. More than 285 people in seven countries were killed before the hurricane dissipated. By Oct. 29, Sandy had moved ashore near Brigantine, N.J., just northeast of Atlantic City, as a post-tropical cyclone with hurricane-force winds.

When it came ashore, it ran into other storm fronts coming in from the Midwest and down from Canada, a rare confluence that turned what would have been a bad hurricane into a disastrous superstorm. The severely energized storm affected parts of 24 states including the East Coast from Florida to Maine. It was a Category 1 hurricane covering an astounding 1.8 million square miles, according to NASA.

THE DAMAGE: The superstorm winds combined with incoming tides to flood low-lying areas and the famed tunnels of Manhattan, isolating the island from the rest of the city. A broad area south of 34th Street was cut off from transportation and cellphone service failed. For many people, the answer to the question, “Can you hear me now?” was a decisive NO.

In parts of Brooklyn and Queens, flooding forced electrical generators to fail, ending elevator service to high-rise buildings. Hospitals were evacuated, food and water was in short supply as gasoline rationing was started.

One of the iconic images of those days of nature’s wrath was a fire that tore through Breezy Point, locally known as the Irish Rivera, and a popular place for many city workers, including firefighters. At the western tip of the Rockaway Peninsula, it is essentially a enclave that bore the brunt of fire and water. It is estimated that 350 homes, more than 10% of the area’s houses, were destroyed by fire or flood and had to be demolished.

Today, more than a third of those homes remain unoccupied. Just six months ago, the area was 85% empty, officials told Newsday.

Hardest hit were parts of New York and New Jersey, though Connecticut took the brunt as well.

THE RECOVERY EFFORT: The rebuilding efforts remain huge. The National Climatic Data Center estimated the cost of Sandy at $65 billion, behind only Hurricane Katrina on the list of costliest disasters ever to hit the United States. Some people have used up their emergency benefits and are still seeking long-term housing. Whole communities from the Oakwood Beach area of Staten Island to Breezy Point, N.Y., to Long Beach on Long Island still need help despite hundreds of millions of dollars already spent – in some cases to buy out homeowners who stand no chance of rebuilding since land was washed into the sea.

Last week, officials announced the latest tranche of more than $2 billion from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to fund homeowners’ and businesses’ recovery from Sandy. The state’s action plan calls for at least 80% of all HUD funding to go to Long Island and Rockland County. In the spring, HUD gave New York state an initial $1.71 billion. New York City received $1.77 billion in separate funding from HUD.

The allocations come from the Disaster Relief Appropriations Act of 2013, which authorized $60 billion in federal money for Sandy disaster recovery. That bill also caused a split among GOP House members, some of whom questioned the size of the aid package for Democratic New York and for New Jersey, whose Republican Gov. Chris Christie famously embraced a visiting President Obama during what was a contentious presidential campaign.

Christie, who is running for re-election and is considered a possible presidential contender in 2016, has long defended his big political hug of the president – especially annoying to conservatives Christie may need if he decides to run for higher office. In the current race, he has praised his administration’s efforts to rebuild, especially in tourist areas, and has blamed the federal government for not moving quickly enough to keep open the spigots of federal dollars.

The image that caught the resorts’ pain from the days after the storm was the famed roller coaster in Seaside Heights, N.J. The ride had washed out to sea and became a minor tourist attraction until it was demolished in May.

A recent report from Rutgers-Newark School of Public Affairs and Administration estimated that New Jersey towns and residents across the state still face $28.3 billion in unmet recovery needs.

“We’ve done everything we possibly can, and I think in the immediate aftermath did a very good job,” Christie told the Associated Press in a recent interview. “Since then, we’ve kind of been hostage to two situations, the delay in the aid itself and then what I call the ‘Katrina factor,’ which is the much more detailed and difficult rules surrounding the distribution of the aid.”

Asked about the delay, Christie said cumbersome federal requirements are responsible. “To the victims, I’d say you’re right, it is too slow, and I wish that the federal government would allow us the flexibility to get you aid more quickly,” Christie said.

But some things are getting done.

New York has begun work on protecting its tunnels from encroaching seawater, though much more is still be funded. The state has also moved to establish a fuel reserve of its own to help ease future crunches. It has also sought to have service stations provide back-up generators so that critically needed gasoline can keep flowing.

Still, many argue that Sandy is just a symptom of the changing climate and that government needs to figure out a better way of dealing with extreme storms. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo again made that point at a conference on Monday to discuss lessons learned from Sandy.

“After experiencing Superstorm Sandy, Hurricane Irene and Tropical Storm Lee in the last few years, it is clear that New York state must be prepared for today’s ever-changing climate,” Cuomo said. “This conference provides an opportunity for first responders and local officials to discuss the lessons we have learned from the three ‘100-year storms’ we’ve incurred in the last three years that impacted communities across the state and take actions to address future emergencies, both natural and man-made.”

ALSO:

Phoenix family of four killed by neighbor, police say

N.C. fair operator accused of tampering with ride that injured 5

As Danvers mourns teacher, suspect’s mother says ‘heart is broken’

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.