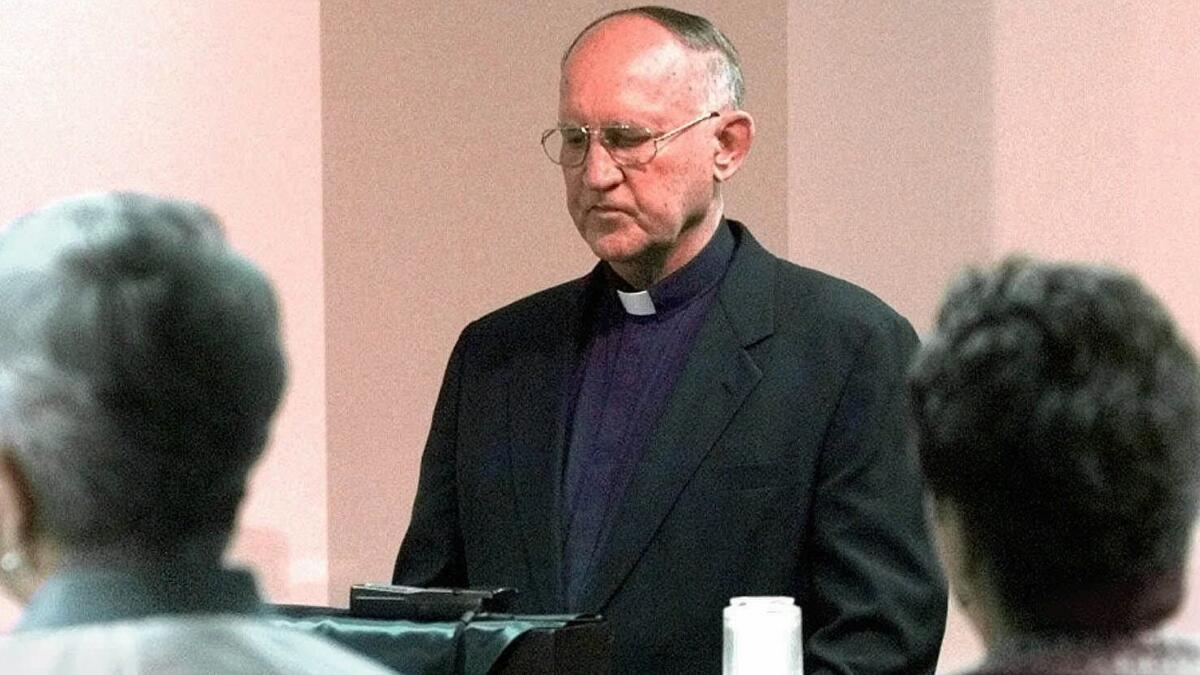

Texas Catholic leaders name 286 priests and others accused of child sex abuse

- Share via

Reporting from Dallas — Catholic leaders in Texas on Thursday identified 286 priests and others accused of sexually abusing children, a number that represents one of the largest collections of names to be released since an explosive grand jury report last year in Pennsylvania.

Fourteen dioceses in Texas named those credibly accused of abuse. The only diocese not to provide names, Fort Worth, did so more than a decade ago and then provided an updated accounting in October.

There are only a few states where every diocese has released names, and most of them have only one or two Catholic districts. Arkansas, for instance, is covered by the Diocese of Little Rock, which in September provided a preliminary list of 12 former priests, deacons and others. Oklahoma has two districts: The Archdiocese of Oklahoma City is scheduled to publicly identify accused priests on Feb. 28, and the Diocese of Tulsa previously named two former priests accused of predatory behavior.

The move by Texas church leaders follows a shocking Pennsylvania report in August detailing seven decades of child sexual abuse by more than 300 predator priests. Furthermore, the Illinois attorney general reported last month that at least 500 Roman Catholic clergy in that state had sexually abused children.

In the months after that report, about 50 dioceses and religious provinces have released the names of nearly 1,250 priests and others accused of abuse. Approximately 60 percent of them have died. About 30 other dioceses are investigating or have promised to release names of credibly accused priests in the coming months.

In Texas, the Diocese of Dallas and some others relied on retired police and federal investigators to review church files and other material to substantiate claims of abuse. It’s not clear whether any of the names released Thursday could result in local prosecutors bringing criminal charges. The majority of those identified have since died. Some investigations dated back to 1950, while other reviews, as in the case of the Diocese of Laredo, only went to 2000 because that’s when that diocese was established. Of the 286 men named in Texas, 172 have died, a percentage comparable with the national tally.

“Our office stands ready to assist local law enforcement and any district attorney’s office that asks for our help in dismantling this form of evil and removing the threat of those who threaten Texas children,” said Marc Rylander, spokesman for the Texas attorney general’s office. “To date, we have not received any such requests, but we are ready to provide assistance to local prosecutors in accordance with state law and original criminal jurisdiction.”

The head of the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston, Cardinal Daniel N. DiNardo, also is president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and is expected to attend a February summit called by Pope Francis to sensitize church leaders around the globe to the pain of victims, instruct them how to investigate cases and develop general protocols for church hierarchy to use.

DiNardo said in a statement Thursday that “the Bishops of Texas have decided to release the names of these priests at this time because it is right and just and to offer healing and hope to those who have suffered. On behalf of all who have failed in this regard, I offer my sincerest apology. Our church has been lacerated by this wound and we must take action to heal it.”

In a statement released with the report of the San Antonio Archdiocese, which had the longest list of names among Texas dioceses, with 56 dating to 1940, Archbishop Gustavo Garcia-Siller said the abuse allegations and the mishandling of some by bishops “are tearing the church apart.” Although the release of the report “brings tension and pain,” the archbishop said he was “filled with serenity and peace” by the disclosures.

Victim advocates and those who have been tracking clergy abuse for decades have said the church has a bad record of policing itself and law enforcement investigations into church records of allegations are the only way to ensure real transparency. They argue that there is no uniform definition of credibly accused priests and dioceses use different standards when deciding what names to release.

For example, the San Antonio Archdiocese examined decades of allegations made against clergy and religious order priests dating back decades. The Diocese of Laredo released no names after its bishop said staff had examined its records for the 19 years since it was created, shortly before stricter standards for handling abuse allegations were instituted across the church, and found no credible allegations.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.