Supreme Court dissenters signal historic challenge to death penalty

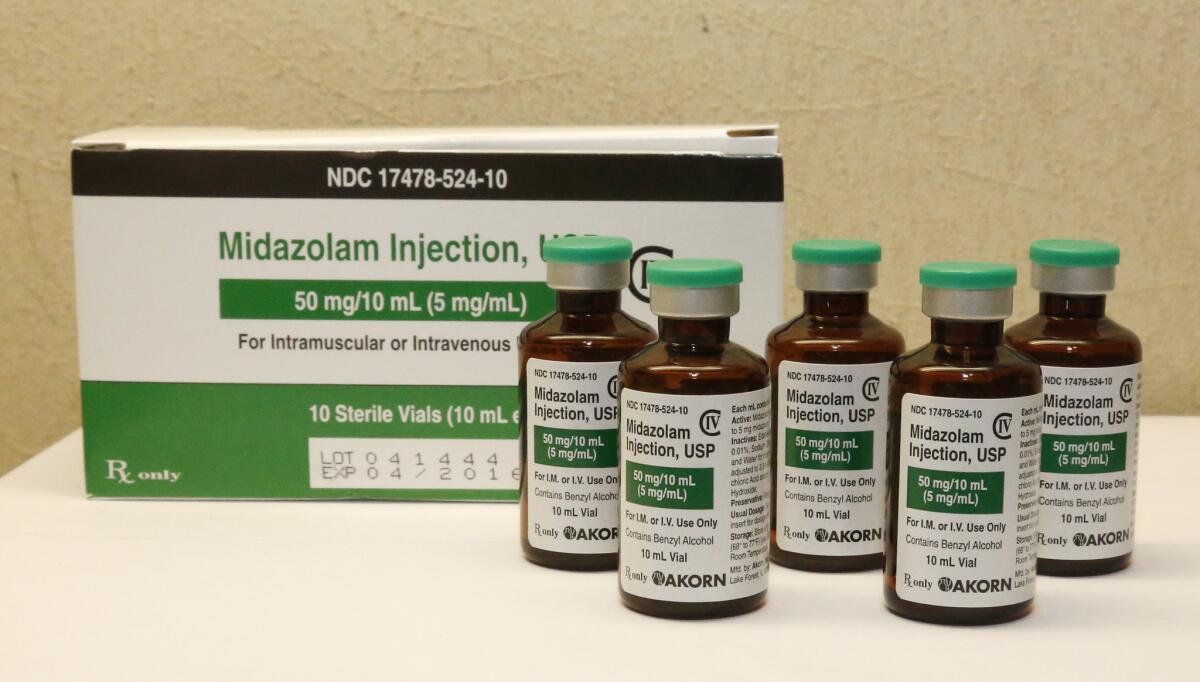

By a 5-4 vote, the Supreme Court gave Oklahoma, Florida and other death penalty states the go-ahead to administer midazolam, a surgical sedative, as one of the drugs used in lethal injections.

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — The Supreme Court cleared the way Monday for Oklahoma to continue using a lethal drug cocktail for executions, but, in a surprising dissent, two liberal justices opened the door to what could become a historic challenge to the death penalty itself.

By a 5-4 vote, the court’s conservative justices gave Oklahoma, Florida and other death penalty states the go-ahead to administer midazolam, a surgical sedative, as one of the drugs used in lethal injections.

But opponents of the death penalty took heart from a meticulously researched and unusually passionate dissent from Justice Stephen G. Breyer, who openly invited a new constitutional assault on the very foundation of capital punishment.

The death penalty, Breyer wrote, is “unfair, cruel and unusual.” Opponents of the ultimate punishment took his words as a call to arms.

“I think this case will be remembered more for that dissent than for the decision itself,” said Richard Dieter of the Death Penalty Information Center in Washington. Breyer “has sort of planted a flag for the courts to have a discussion of the death penalty itself. This is going to be a blueprint for saying the country has turned a corner on the death penalty.”

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg joined Breyer’s opinion, and the two other liberal justices dissented strongly from Monday’s ruling, giving the campaign to abolish the death penalty its biggest momentum at the high court in nearly four decades.

In 1972 the justices suspended the use of the death penalty, but reinstated it four years later. Monday’s dissent marked the first time since the early 1990s that two sitting Supreme Court justices have openly questioned the legality of capital punishment.

Their move comes at a time when public opinion has shifted dramatically from strongly to narrowly in favor of executions. The share of the public that supports the death penalty has declined more than 20 percentage points since its peak in the mid-1990s, and by 6 percentage points since 2011, according to a Pew Research Center poll released in April. Support now stands at 56% with opposition rising to 38%.

The issue has also become far more partisan. Most of the rise in opposition to the death penalty has come from Democrats and to a lesser extent independents. Republican support has also declined, but not nearly as much. As a result, today about 75% of Republicans support the death penalty compared with 40% of Democrats, Pew found.

A growing number of states are already taking action. Nebraska last month abolished the death penalty, becoming the 19th state to do so and the seventh since 2007.

At the Supreme Court, a majority of the justices still believe capital punishment is constitutional, including Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Justices Antonin Scalia, Anthony M. Kennedy, Clarence Thomas and Samuel A. Alito Jr., who wrote the opinion in the case of Glossip vs. Gross.

However, if one of them were to leave the high court, support for capital punishment there could come into question, particularly if the next president appointed a more liberal justice.

Since the retirements of liberal Justices William J. Brennan Jr. and Thurgood Marshall in the early 1990s, all of the justices had voted in favor of the death penalty. But shortly before he retired, Justice Harry Blackmun announced that he had come to believe capital punishment was unconstitutional. In 2008, Justice John Paul Stevens did much the same, deciding the death penalty did not work reliably as a deterrent or an effective punishment.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor did not join Breyer’s statement but wrote the strongest dissent in the Oklahoma case. She accused the majority of allowing a “method of execution that is intolerably painful — even to the point of being the chemical equivalent of burning alive.” Justice Elena Kagan agreed with her.

Proponents of abolishing the death penalty said they would use Breyer’s dissent as a launching pad to mount what they envision as a long-term effort, something akin to the years-long campaign for same-sex marriage that finally came to fruition with Supreme Court approval Friday.

“The time has come to raise a constitutional challenge, to be thinking about the ways that the death penalty violates the Constitution and how best to prove that,” said Cassandra Stubbs, director of the Capital Punishment Project of the American Civil Liberties Union.

The bitter rift among the justices over the death penalty was apparent in the case of Richard E. Glossip, who was convicted in the 1997 murder of his boss. Oral arguments in April provoked what some observers thought was the sharpest dispute the court has seen in many years.

Though it’s unusual for dissents to be read from the bench, on Monday both Breyer and Sotomayor read their dissents aloud. Then, even more unusually, Scalia opted to read aloud from his concurring opinion to counter the arguments of the dissenters. “Welcome to Groundhog Day,” Scalia said derisively, complaining that dissenters were raising familiar complaints about the death penalty.

Scalia said the court’s liberals had made it impossible for states to carry out the death penalty in a reasonable time by requiring an exhaustive review process, and they then complain about the long and costly delays. “Justice Breyer has been the drum major in this parade,” he said.

Alito’s decision focused on the mechanics and challenges states face in carrying out executions. The most effective barbiturates, including sodium thiopental, can no longer be obtained by prison authorities because anti-death-penalty advocates lobbied the drug’s Danish manufacturer to stop selling it for executions, Alito said.

As a fallback, Oklahoma authorities switched to midazolam, and they argued that a massive dose puts an inmate into a deep sleep. Only then do officials administer powerful and searing drugs to stop the heart. Alito and four others rejected claims from defense lawyers that this sedative is ineffective and may result in “cruel and unusual punishment.”

“Because some risk of pain is inherent in any method of execution, we have held that the Constitution does not require the avoidance of all risk of pain,” he said. “After all, while most humans wish to die a painless death, many do not have that good fortune. Holding that the 8th Amendment demands the elimination of essentially all risk of pain would effectively outlaw the death penalty altogether.”

The state’s execution chamber was thrust into the national spotlight in April 2014 after Oklahoma botched its first execution using midazolam. Clayton Lockett, the condemned man, awoke in apparent agony after the drugs were administered. He died after a long struggle, apparently of a heart attack.

Death penalty foes said the gruesome spectacle confirmed their view that lethal injections should not go forward unless the states find an effective barbiturate. But Oklahoma prison officials blamed the incident on a botched effort to inject the inmate’s veins, not a failure of the midazolam.

Kent Scheidegger, legal director of the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation in Sacramento, praised the majority decision. “The death penalty is supported by the vast majority of the American people. Justice in these horrible cases must not be obstructed by a conspiracy to cut off the needed drugs,” he said in a statement.

In California, which has the most people on death row of any state, Gov. Jerry Brown’s administration has agreed to propose a new lethal injection method within 120 days, as part of a legal settlement in a case brought by Scheidegger’s organization.

Until now, Breyer, who has served 20 years on the high court, never contended the death penalty was unconstitutional. He and Ginsburg argued that new evidence over the last two decades had convinced them the death penalty is costly, ineffective and unreliable. More than 100 prisoners condemned to death had their convictions or sentences thrown out in the last decade, he said.

“Last year, in 2014, six death row inmates were exonerated based on actual innocence. All had been imprisoned for more than 30 years,” Breyer said.

While state officials complain the appeals in these cases last decades, Breyer said the recent exonerations show it would be mistake to speed up the appeals process. Doing so would almost surely lead to executing innocent people, he said.

“In sum, the administration of the death penalty can take place swiftly but unreliably or it can take place with long delays but without significant justifying purpose,’’ he concluded. “We cannot have it both ways.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.