As MERS virus reaches U.S., public health system springs into action

- Share via

Reporting from Munster, Ind. — The man arrived at the hospital with a fever and a bad cough. Relatives accompanied him through the doors, beneath the red neon sign reading “Emergency.”

It looked like pneumonia, but when doctors at Community Hospital learned that the patient was a healthcare worker in Saudi Arabia, they began suspecting something more sinister.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

MERS virus: An article in the May 10 Section A said a man infected with the deadly Middle East respiratory syndrome, or MERS, took a bus trip from Chicago to Indiana on April 27. He made the trip on April 24, the same day he arrived in Chicago on a flight from Saudi Arabia. —

------------

Swabs from the man’s nose and mouth confirmed it: The United States had its first case of a new and often deadly ailment called MERS, or Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, and health experts were facing a medical drama that all of them had anticipated but none of them ever hoped to see.

Over the last week, investigators have worked to track down every person who shared space with the unidentified elderly patient before he showed up at the hospital, including passengers on the April 24 flight that brought him from the Saudi capital of Riyadh to Chicago O’Hare International Airport. Through passenger manifests, credit card receipts and other clues, they have also traced people who rode with the man on the bus he took from the airport to northwestern Indiana on April 27.

So far, nearly all the fellow travelers — about 112 — have been traced, and none has tested positive for the crown-shaped virus that causes MERS. At least 50 hospital workers who had even the slightest contact with the man remain in home isolation, but they also show no symptoms. The same is true for the Indiana relatives whom the man, an American living in Riyadh, had come to visit.

On Friday, the MERS patient was cleared to leave the hospital and authorized to travel.

“It appears we have contained this,” Alan Kumar, chief medical information officer at Community Hospital, said this week.

For the last two years, since the virus that kills one-third of those it infects first appeared on the other side of the world, on the Arabian Peninsula, U.S. epidemiologists have waited and prepared for the day it would appear in this country.

“Anyone is a planeload away from any disease on Earth,” said Indiana’s state epidemiologist, Pam Pontones.

The response in Munster, a bedroom community about 30 miles south of downtown Chicago, was a textbook example of how the public health system is supposed to work, said those involved in this case, citing the rapid diagnosis and the quick tracing of the patient’s contacts.

Warnings from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were carried to state health officials and from there to healthcare workers on the front lines — who, months down the road, remained attentive enough to ferret out an infected patient in time.

“It’s really cool, when you think about it,” said Johns Hopkins epidemiologist Trish Perl, who studies the virus.

But medical experts say that although this case was handled successfully, it is a sign of things to come and highlights the need for continued heightened vigilance, as people crisscross the globe with greater frequency than ever before.

“It’s a small world these days,” said Daniel Feikin, an epidemiologist with the CDC in Atlanta. Feikin was the leader of a six-member team of specialists who came to Indiana on May 2, the day the agency confirmed the Munster patient had MERS.

“Diseases don’t respect borders,” Feikin said. “In this day and age, we need to be prepared for diseases coming to the United States.”

Health officials have been keeping a close eye on the virus since scientists first discovered it in a 60-year-old Saudi man, who died in 2012 after suffering pneumonia and kidney failure. By June 2013, nearly 80 people in the region had been infected with MERS, and more than half had died. Saudi Arabia, which has been hit hardest by MERS, reported Wednesday that it had recorded 449 cases and that 121 of those infected had died.

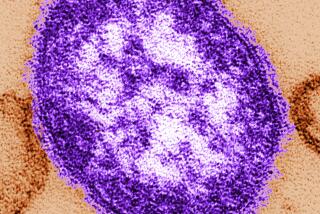

MERS worried medical experts because it seemed to bear a resemblance to SARS, another coronavirus that infected nearly 8,500 people in 2003 and killed more than 800, mostly in Asia.

MERS, which has also been found in camels and bats, does not appear to be as contagious as SARS, however. It seems to spread through prolonged and close contact, meaning relatives of victims and healthcare workers tending to victims are the most vulnerable.

But when it hits, it often is deadly. There is no treatment, so MERS patients get standard “supportive” care for respiratory infections, such as medication to reduce fevers and oxygen to aid breathing.

The World Health Organization reported that as of April 24, MERS had killed nearly 37% of 254 confirmed victims. On Tuesday, the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control, which compiles its own statistics, reported a 28% death rate among 495 cases globally.

That mortality level is “reminiscent of the way things were in the pre-antibiotic era,” said Robert Quigley, International SOS’ medical director for the Americas. The company provides medical and other crisis services for corporate clients. Among its clients, more than 36,000 U.S.-based travelers made 83,214 trips to the Arabian Peninsula — the breeding ground for MERS — between April 1, 2013, and April 30, 2014, underscoring the risk of the virus’ spread.

Pontones and the state health commissioner, William VanNess II, learned that MERS might be in their midst April 30, a Wednesday, two days after the patient showed up at the Munster hospital. When the man arrived at the emergency room two nights earlier, he was able to walk on his own. But he was sick enough that he was given oxygen and put in a private room with negative air flow, which prevented air in his room from mixing with air in the rest of the hospital.

Healthcare workers wore masks, gloves and gowns as they tended him. His fever spiked to 102.7 degrees, and his symptoms were similar to those of the flu or pneumonia. A team of doctors at Community, a 427-bed facility, interviewed the patient’s family and learned that he had flown to Chicago, via London, from Riyadh four days earlier.

When they learned that he worked at a medical facility, the team — aware of MERS because of CDC warnings — alerted Indianapolis that a possible MERS sample was being sent there for testing.

On the afternoon of May 1, a respiratory epidemiologist in Indianapolis phoned the CDC.

The sample was positive.

The next day, the CDC did its own test, confirmed the state’s finding, and deployed a team to work with state and local officials to contain the threat.

The man’s relatives — officials wouldn’t say how many — were tested and told to stay home and to wear masks if they had to go out. The hospital used video surveillance and GPS-like devices worn by staff to determine which employees had encountered the patient. They were tested and sent home for two weeks of isolation.

A telephone hotline was set up for people to call for information as the hospital, the CDC, and the state announced the MERS case in news releases and on social media. They urged anyone who might have been near the patient, including those who were on the shuttle bus from the airport, to get tested.

“It was like, let’s get out the facts, but let’s not create panic,” said VanNess. “We didn’t want everyone fleeing northwestern Indiana.”

At least 114 calls have come into the hotline since it was established May 3, but the frequency is decreasing. Health officials seem confident that they stopped MERS before it could spread, thanks to Community Hospital’s quick response. They also benefited from timing: The patient had no symptoms during his flight, so he probably was not contagious at the time.

But everyone tested will be retested, at the two-week mark after their initial swab, before they get the all-clear to emerge from isolation. And even after the patient is released from the hospital, he will have to spend some time in isolation and be monitored for illness before he can fly back to Saudi Arabia.

“We’re feeling encouraged, but we’re being overly cautious,” said Feikin. “This is a new disease.”

Susman reported from Munster and Brown from Los Angeles.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.