Residents of low-income South Bronx want reassurance amid Legionnaire’s disease crisis

- Share via

Reporting from New York — This summer’s deadly outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease in the South Bronx was described by one politician here as an “unfortunate perfect storm” — invisible clouds of contaminated mist from commercial cooling towers swirling down into one of this city’s poorest areas, whose population already struggles with health problems associated with poverty.

The result: the worst outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease in New York state history — 115 cases and 12 deaths since the middle of July. No one was prepared for the ferociousness with which the disease struck the South Bronx.

That the outbreak occurred in one of the city’s least-affluent areas was not lost on residents.

At a town hall meeting Tuesday, Shirley Doran, 75, said she and others in the South Bronx were looking for assurances that they were safe from the disease. “We want to know if it’s all cleaned up,” she said. “What’s being done?”

City health officials emphasized that healthy people were less likely to contract the disease than those who were elderly, suffered from lung disease or had diabetes or other underlying conditions that weakened their immune systems.

“That is not comforting to us,” one woman said at the town hall.

“We’re having a lot of problems with breathing,” said another woman who stood up to note that asthma is widespread in the area.

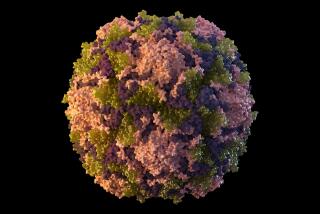

Legionnaires’ disease is a pneumonia-like illness that is contracted by breathing in Legionella bacteria, usually from tainted vapors. Incubation time can be as long as 10 days. City officials were able to pinpoint cooling towers in commercial heating and air conditioning systems as the source.

The South Bronx is a mixture of residential neighborhoods and industry, and large cooling systems can be seen on many buildings dotting the area’s gritty skyline. Of 39 such cooling towers in the South Bronx tested for Legionella since the outbreak began, 14 were found to have been contaminated, city officials said Wednesday. Six sites elsewhere in the Bronx also have tested positive.

Diana Hernandez, a professor of sociomedical sciences at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and a South Bronx resident, described the neighborhood as one of “concentrated poverty … saturated with poor health” in an op-ed piece published in Wednesday’s New York Daily News.

“These conditions make the South Bronx ground zero for diseases that prey on the most vulnerable — of which Legionnaires’ disease is one,” Hernandez wrote. “If New York caught a cold, the South Bronx would get pneumonia.”

Research clearly documents the poverty and poor health in the South Bronx.

A 2014 study published on the state’s Health Department website said Bronx County was the unhealthiest in the state, “burdened by a myriad of health challenges and socioeconomic circumstances that foster poor health outcomes.” Its residents suffered from high rates of diabetes, heart disease, asthma, cancer and obesity, the study said.

And the South Bronx has fared even worse, crippled by the weight of extreme poverty. In four neighborhoods — Mott Haven, Melrose, Hunts Point and Longwood — the poverty rate among residents in 2013 stood at 42.3%, more than double the citywide rate of 20.9%, according to report by the New York University Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy.

State Sen. Jose M. Serrano, a lifelong resident of the South Bronx, is certain the overall poor health of the area was a factor in how quickly the disease spread.

“We have a high instance of asthma, diabetes. We have an aging population and all of the issues that go along with health disparities — access to healthcare, access to healthy food, access to green space,” Serrano said in an interview. “When you add them all up and put them all together, they create this unfortunate perfect storm where an outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease can have a devastating effect.”

Over the last several weeks, as the deadly impact of the outbreak struck home, city officials moved quickly to test and clean cooling towers in the Bronx, reassure residents by holding town hall meetings and distributing thousands of informational fliers, and draft legislation that would require regular monitoring and cleaning of such towers across the city — regulations that had not been in place before this latest Legionnaires’ emergency.

The legislation is being drafted jointly with state officials, and Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo said he would impose similar regulations across the entire state.

The city first said cooling towers were the likely source of the outbreak on July 30, when officials identified five contaminated sites.

The city was not without warning that cooling towers were potential culprits for Legionnaires’ disease outbreaks. In January, eight cases at a housing complex in another part of the Bronx were linked to a cooling tower. And a water system at a senior citizens’ center in Flushing, Queens, was deemed the source of nine cases reported there in May.

Health officials say they see 200 to 300 cases of Legionnaires’ disease in the city each year, but never in the concentrated way it appeared in the South Bronx this summer.

A study published by city Health Department researchers in November identified risk factors of Legionnaires’ disease in the city by analyzing cases between 2002 and 2011. The results foreshadowed the South Bronx disaster, having documented a sharp uptick in cases in recent years.

“Overall, incidence of Legionnaires’ disease in the city of New York increased 230% from 2002 to 2009 and followed a socioeconomic gradient, with highest incidence occurring in the highest poverty areas,” the study’s findings stated.

The researchers recommended public health officials pay special attention to potential sources of Legionella bacteria in poorer neighborhoods.

“If environmental issues in high-poverty neighborhoods contribute to the disparity, greater effort may be warranted, for example, on the upkeep of cooling towers and water systems in the buildings in these areas,” the study stated.

At a town hall meeting last week, Bronx Borough President Ruben Diaz Jr. said he would make sure that the government responded adequately to the crisis, adding that residents of the South Bronx would not tolerate being treated like “second-class citizens.” His remarks drew applause from the several hundred people in the audience.

Several days later, Diaz bypassed Mayor Bill de Blasio and contacted Cuomo for help. The governor responded by sending teams of state health officials, joined by representatives of the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, to the Bronx to expand the testing of cooling towers outside the area affected most.

And while Diaz has not directly criticized the city’s actions, he said in an interview, “We needed to see more of an effort, more hands on deck. We needed to make sure that we addressed the problem that people are dying.”

With the outbreak appearing to be on the wane, residents of the South Bronx remain scared and vulnerable even as they go about their usual business.

During the evening commute Tuesday, people streamed out of the subway stop at the Grand Concourse and 149th Street, a hub of the South Bronx. Sidewalks were crowded and residents stopped to pick up groceries on their way home.

But signs that not all was right in the neighborhood were evident. At the post office on one corner of the intersection, steps were cordoned off with police tape and the doors locked while the building was being testing for Legionella. On Wednesday, officials announced it had tested positive.

“I’m sometimes scared and worried,” said George Heyward, 47, a resident who attended Tuesday’s town hall. “Where did it start and how are you going to get rid of it?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.