Analysis: Echoes of Iraq war sound in 2016 presidential race

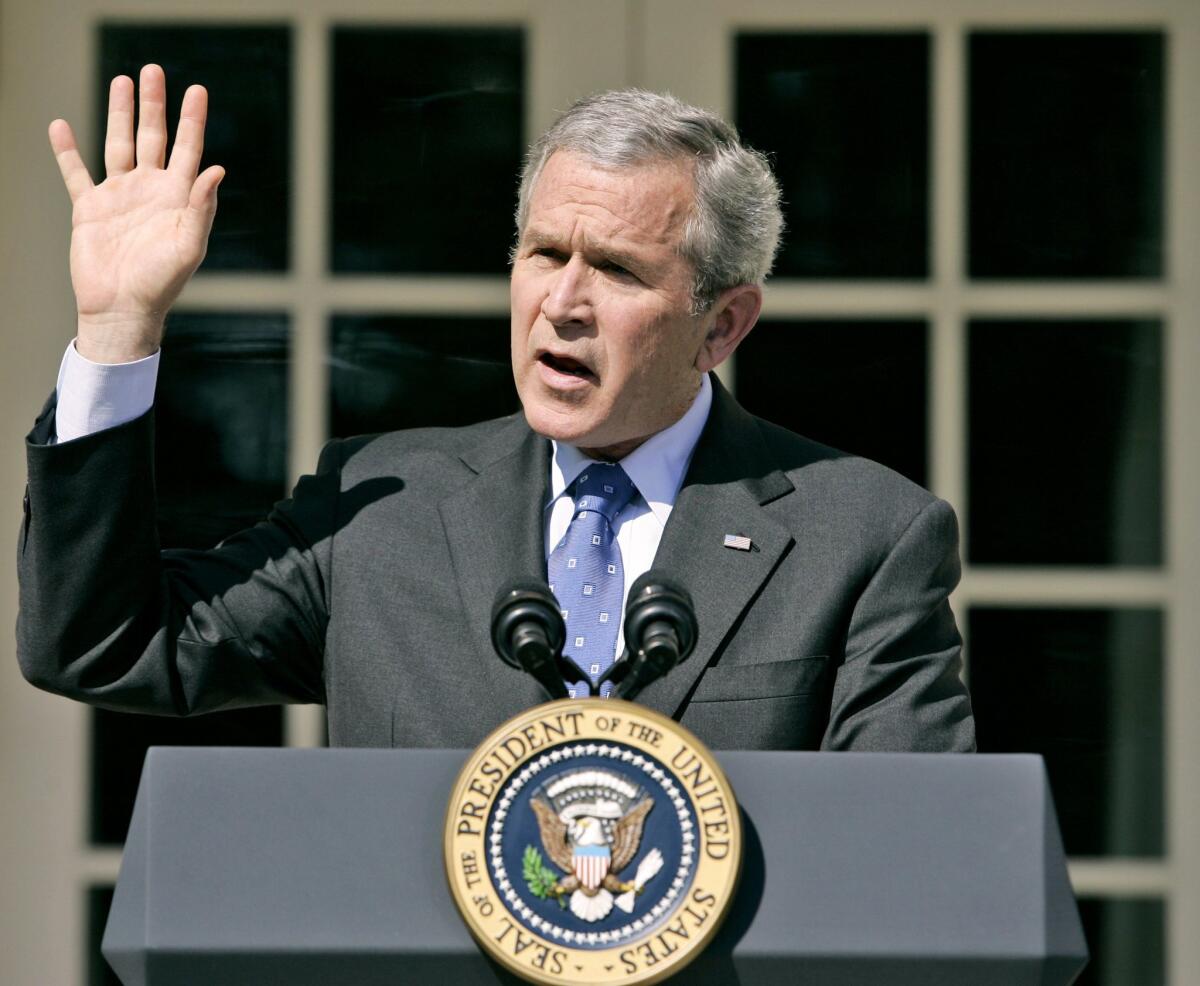

Twelve years after President

- Share via

Every war casts a long shadow, from the heroism of the Greatest Generation to the dark ambiguities of Vietnam. It was inevitable, then, that the 2016 presidential candidates would be confronted with the war in Iraq.

Twelve years on, the broad questions raised by the invasion — about trust in Washington and its leaders, about faith in dubious overseas alliances, about the best ways to fight terrorism and how to bring peace to the Middle East, if that’s even possible — have not gone away.

If anything, the politics have grown more fraught for members of both parties.

Kentucky Republican Rand Paul seized the Senate floor Wednesday for a 101/2 -hour speech aimed at ending the domestic surveillance program that grew out of the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 — part of President George W. Bush’s justification for war.

The accusations of government overreach have been a centerpiece of Paul’s presidential bid and made him a champion to privacy advocates and the libertarian-minded. But it also sets him against Republicans eager to portray the freshman lawmaker as feckless and too quick to drop the nation’s guard.

In a mocking speech, New Jersey’s Republican Gov. Chris Christie laced into those he called “civil liberties extremists,” who he said were trying to convince Americans “there’s a government spook listening in every time you pick up the phone or Skype with your grandkids.”

“They want you to think that if we weakened our capabilities, the rest of the world would love us more,” Christie told a New Hampshire audience on Monday. “Let me be clear: All these fears are exaggerated and ridiculous.”

The challenge for candidates like Christie and others in the GOP field is to sound tough — certainly tougher than President Obama is perceived — without appearing belligerent or too eager, as some now fault Bush, to go to war.

Familial ties make that balance all the more acute for his brother, Jeb Bush, should he emerge as the Republican nominee, which is why his ham-handed performance last week — seemingly for the Iraq war before he was against it — was so unexpected and potentially damaging.

The former Florida governor spent days calibrating and recalibrating a series of statements before flatly declaring that, in retrospect, the invasion should never have occurred. “Knowing what we know now, I would not have engaged,” Bush said. “I would not have invaded Iraq.”

The question could not, or at least should not, have caught him by surprise, raising doubts about Bush’s campaign faculties after a years-long layoff; several GOP rivals were quick to align themselves with popular sentiment, saying they would never have gone to war given the knowledge they possess today.

“I don’t know how that was a hard question,” said former Pennsylvania Sen. Rick Santorum, turning the knife.

Bush, however, was not alone among Republicans. On Sunday, in a convoluted Fox News interview, it was Florida Sen. Marco Rubio’s turn to weave and stumble about the issue, defending President Bush’s decision to invade Iraq, given his thinking at the time, while suggesting it was a mistake he would not wish to repeat.

For the Democratic candidates, familiar divisions surrounding the war have also begun to emerge.

Some on the left have never forgiven the party’s favorite, Hillary Rodham Clinton, for backing the war as a United States senator in 2002, and they are once more calling her judgment into question. The former New York lawmaker and secretary of State has expressed regret for her vote many times since, including again this week.

Clinton’s sole announced challenger, independent Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, said in an interview during a March swing through Iowa, a state with a broad pacifist streak: “I think the war in the Mideast, how we got into it and how we’re going to address the current problems, are issues that every American should be concerned about.” He opposed the Iraq war, he tells audiences, from the start.

Since 2003, when the Iraq war began, every presidential campaign has been shaped to some degree by the U.S. invasion, its faulty pretense — weapons of mass destruction that were never found — and the war’s vexing aftermath.

President Bush might not have been reelected in a close 2004 race but for voters’ reluctance to replace him in the throes of the conflict.

His successor, President Obama, would probably not be in office today had his antiwar position not given him the traction in 2008 to take on Clinton, who was then — as now — the overwhelming favorite for the Democratic nomination.

But politically it is no longer as simple as being for or against the Iraq invasion.

After the withdrawal of U.S. troops under Obama, after the drawing of red lines in Syria and the violent birth of the terrorist group Islamic State, critics can no longer blame Bush for all that torments the region.

“In 2008 and 2012 there was only one narrative, and that benefited Democrats,” said Peter Feaver, a Duke University expert on war and public opinion.

“In 2016 there is another narrative, which says President Obama inherited an Iraq that was stable and headed on a trajectory to success and then, through choices of his own, destabilized the situation and so bears responsibility for what happened,” said Feaver, who served on the National Security Council in Bush’s second term.

Ultimately, though, the debate comes back to Bush and his decision to send U.S. troops to topple dictator Saddam Hussein, a move he said would leave the world a better, safer place.

“It’s a generational pivot point,” said Matthew Dowd, a onetime member of Bush’s inner political circle, who was chief strategist for the president’s 2004 reelection campaign before souring on the war in Iraq.

At a cost of $2 trillion and more than 4,000 American lives, the war’s legacy “affects everything,” Dowd said. “What do we do in Syria? What are we willing to do in Iran? How do we pay to fix our railroads and pay for our kids’ college loans?”

“All of this stuff ripples,” he said, and will be debated by presidential candidates for many years to come.

Twitter: @markzbarabak

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.