California regains control over healthcare at Folsom prison

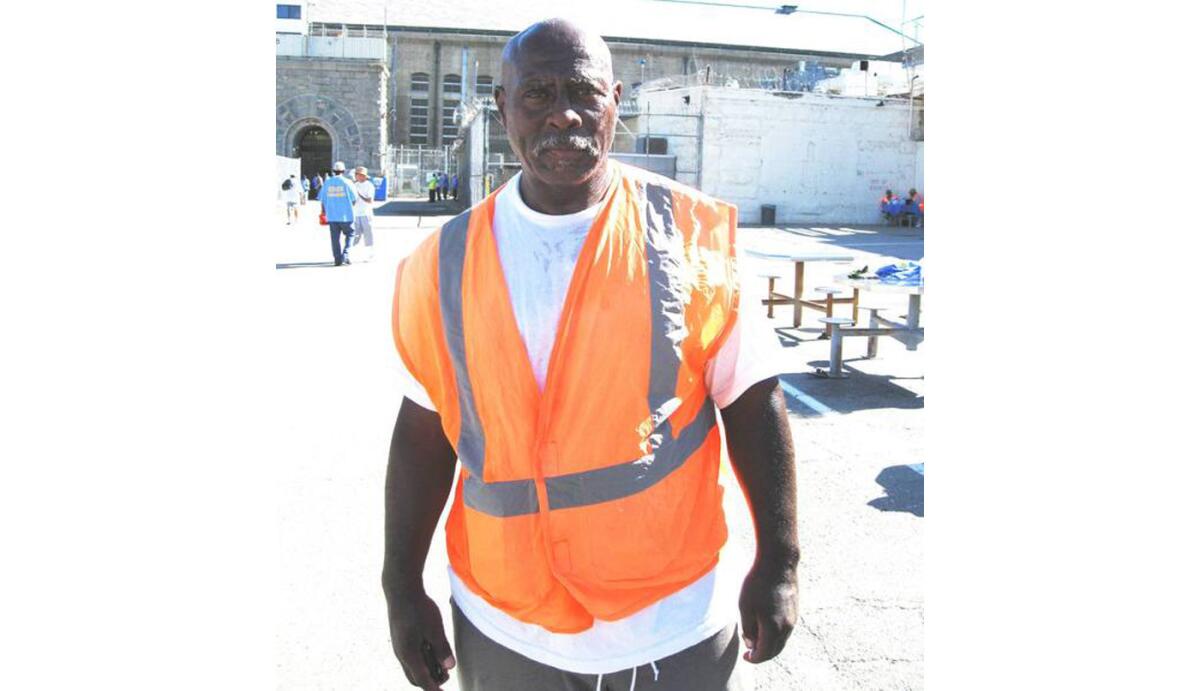

Folsom State Prison inmate Johnnie Calvin Thomas, shown on June 8, said that after 21 years of prison medical care under state and federal control, quality of care still boils down to which doctor sees him.

- Share via

Reporting from Sacramento — The state has regained full control of one of its prisons for the first time since 2006, when a federal court stripped California of control over its sprawling inmate healthcare system.

J. Clark Kelso, the overseer of prison medical care and spending, returned responsibility for the health of some 2,400 inmates at Folsom State Prison to California’s corrections department on Monday.

He promised to restore the same authority for more of the state’s other 33 lockups in coming months.

“This is the beginning of a significant movement of the case,” Kelso said in an interview, contemplating an end to nearly a decade of federal intervention spurred by a 2001 lawsuit over prison conditions.

A federal monitor found in 2006 that an inmate a week was dying of preventable causes, including overcrowding that contributed to care so poor it was unconstitutional. The next year, a panel of three federal judges ordered California to sharply reduce its prison population.

The U.S. Supreme Court subsequently cited substandard care and shortages of physicians in upholding that ruling.

This spring, U.S. District Judge Thelton Henderson paved the way for an end to the case when he directed that healthcare oversight be returned to state officials one prison at a time.

State corrections chief Jeffrey Beard said Monday that he was pleased by Kelso’s decision and looked forward to more transfers.

The lead attorney for inmates in the litigation, Don Specter at the Prison Law Office in Berkeley, similarly said the handoff “marks a giant improvement from where we started.”

“I just wish it had happened sooner,” he said.

For now, Kelso is reviewing only those prisons in which the state Office of Inspector General deems medical care is adequate. But approval is not assured.

Kelso decided to keep jurisdiction over two other prisons recently deemed acceptable by the inspector general: the Correctional Training Center in Soledad and the aged California Rehabilitation Center in Norco.

Kelso said his staff was still compiling its own review of the Soledad prison, and he had put off evaluating Norco until state lawmakers decide its fate.

“Its condition is so bad we all assumed it would be closed,” Kelso said.

State Sen. Loni Hancock (D-Berkeley), who chairs the Senate public safety committee, said the Norco prison is crumbling and infested with vermin. In May, she called on the state to shut it down.

To address other challenges in the prison healthcare system, Kelso intends to launch an electronic medical records system in September that will replace a paper system he said is “crumbling under its own weight.” In addition, the state is renovating medical clinics, some in major disrepair.

The inspector general’s office found most aspects of medical care at Folsom to be adequate. But diagnostic services, medical records and the physical condition of its clinics were deemed inadequate, as was the care given eight of 30 inmates whose files were reviewed.

One prisoner with end-stage liver disease was given aspirin, despite its risk of impairing blood clotting, and subsequently died of severe intestinal bleeding.

The report concluded that the errors were not representative of the overall care at Folsom.

“Medical care is a complex dynamic process with many moving parts, and subject to human error even within the best healthcare organizations,” the report stated.

Inmates mingling on the open yard at Folsom, perched on the bluffs of the American River a half-hour east of Sacramento, were less enthusiastic recently about the prospect of a change of hands.

“To be honest, I don’t care who is in control. I just want to be treated,” said Booker Brown, 54, a Folsom inmate since 1991.

In an interview last month, Brown said he suffers from hepatitis C and medical workers will not prescribe him expensive drugs for the infection until his symptoms become worse.

“Isn’t that like saying, ‘Go ahead and die and we’ll treat you’?” he said.

Gordon Tripp, a 57-year-old diabetic, said he received special meals at other prisons but can’t get them at Folsom. “Different prisons do it differently,” he said.

The Prison Law Office visited Folsom in advance of Kelso’s decision and will spend the next year monitoring California’s takeover, Specter said.

He said the prison, located near metropolitan hospitals and places where doctors and nurses are willing to live, was among the easiest to improve. Other California prisons, such as those in remote desert locales, face greater obstacles to quality care, he said.

The court’s two medical receivers — first Robert Sillen, then Kelso — used their authority to order construction of new medical buildings and to ramp up physician salaries.

A 2012 study by the Pew Trust said California spent more than any other state on inmate medical care: $10,200 per prisoner. However, it noted that that was a sharp reduction from a $14,495-per-inmate cost in 2007.

Sillen was fired in 2008 amid an uproar over his $8-billion plan to build new prison medical and dental facilities statewide.

Under Kelso, the state instead built only a prison near Stockton for medical and psychiatric care and a medical building at San Quentin.

Kelso relied on updates to existing facilities elsewhere, along with increased staffing and the court-ordered reductions in inmate crowding.

Twitter: @paigeastjohn

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.