Robin Williams dies at 63; Oscar-winning actor, comic genius

- Share via

When Robin Williams graduated from Redwood High School in Marin County, his classmates couldn’t help themselves: They voted him both “most humorous” and “least likely to succeed.”

He topped them.

Williams became one of the world’s most successful entertainers, an actor and comedian whose energy animated characters who, like himself, seemed to be spinning hilariously out of control — sometimes into dark places that only the “most humorous” can understand.

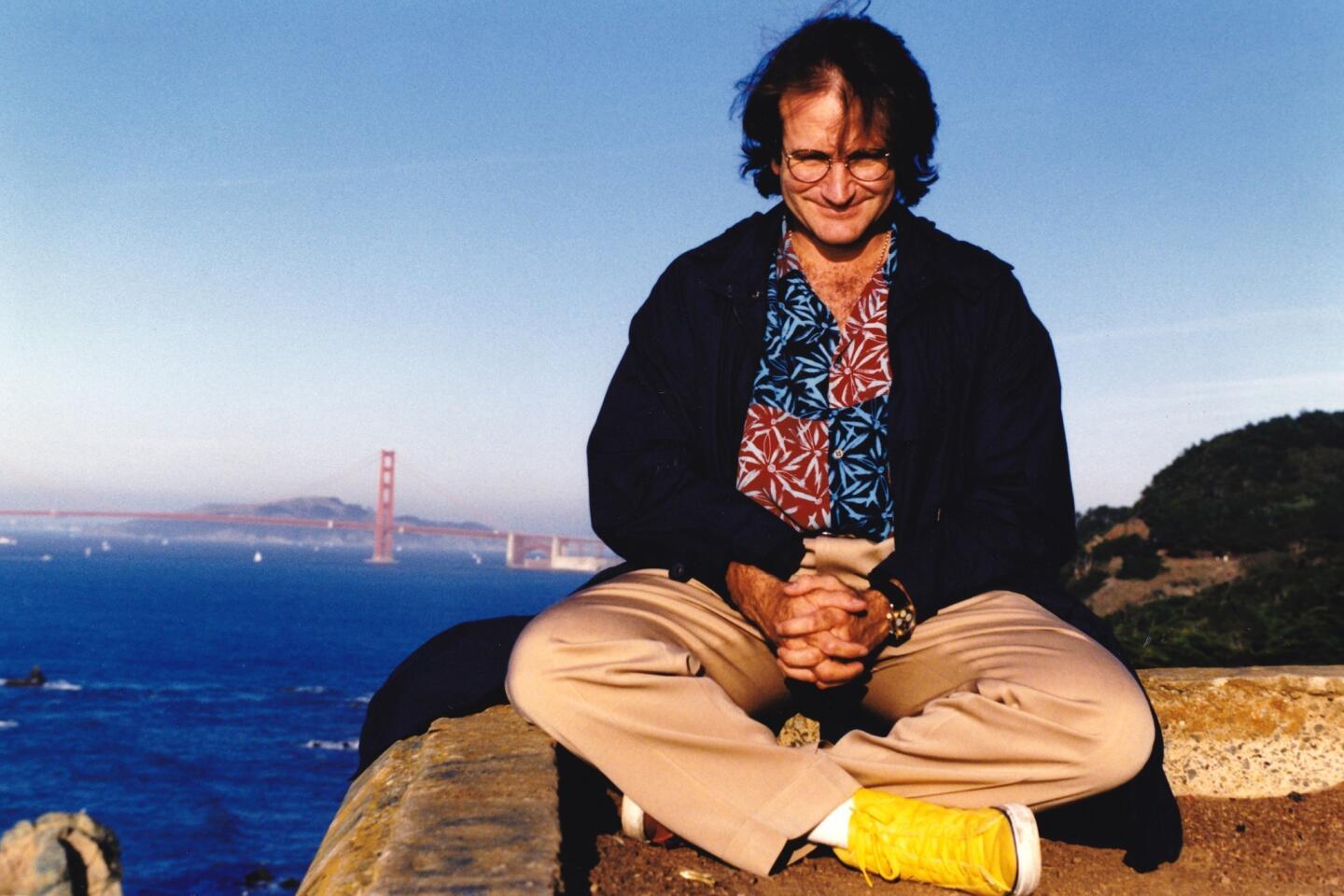

Williams, whose first major role was as a lovable alien in the TV series “Mork & Mindy” but who soon graduated to films such as “Good Will Hunting,” “Dead Poets Society,” “Mrs. Doubtfire,” and “Good Morning, Vietnam,” died Monday in what appears to be a suicide from asphyxiation, Marin County authorities said.

Williams, 63, was found dead in his Tiburon home about noon. Tests to pinpoint the cause of his death were scheduled to start Tuesday.

His publicist, Mara Buxbaum, said Williams had been “battling severe depression of late.”

Over the years, the international superstar struggled with alcohol and cocaine addiction.

“Cocaine for me was a place to hide,” he once told People magazine. “Most people get hyper on coke. It slowed me down.… And I was so crazy back then, working all day and partying most of the night: I needed an excuse not to talk.”

Williams was a close friend of the late comic John Belushi and was with him March 5, 1982, just hours before Belushi died of an overdose at the Chateau Marmont in Los Angeles. The pain of a friend’s death helped Williams kick his own bad habits, but the cure wasn’t permanent.

In 2006, he returned to rehab after two decades of sobriety.

“You’re standing at a precipice and you look down, there’s a voice and it’s a little quiet voice that goes, ‘Jump!’ ” he told ABC News.

Although Williams was said to be quiet and even withdrawn offstage, he was compulsively on much of the time.

In a 1993 Times interview, he was typically free-form when describing how he could inject too much of himself into a role.

“Sometimes you’ll want to use the old lines, go for the laughter, rather than develop the character,” he said.

“The other tendency is for me to be too vulnerable, where the director has to say, ‘OK, that’s a little bit too much,’ and find something that allows the audience to experience it but without gasping for air.

“It’s like an acting teacher said,” he went on, plunging into a thick British accent: “‘Dear boy, that was a lovely scene and your emotions — there was so much of them!’ But it’s a bit like urinating in brown corduroy pants. You feel wonderful, but we see nothing.”

Some of the people who worked closely with Williams knew they were in the presence of a comic genius, but saw him as both warm and remote.

“He was always in character — you never saw the real Robin,” said Jamie Masada, founder and chief executive of the Laugh Factory. “I knew him 35 years, and I never knew him.”

If Williams had a role model, it was Jonathan Winters, the exquisitely comedic and similarly pained soul with a multitude of voices and characters.

“Jonathan has taught me that the world is open to play,” Williams told “60 Minutes” in 1986. “That everything and everybody is mockable — in a wonderful way.”

Williams came to Hollywood prominence in the late 1970s with his starring role in “Mork & Mindy,” a spinoff of the then-popular “Happy Days.”

The comedy, about an alien baffled by the ways of Earth, played off the contrast between how the extraterrestrial Mork viewed the world and how the world really worked. With catch phrases such as “Na-nu-na-nu,” Williams’ character embodied a kind of nerd-sexiness that was more than a quarter-century ahead of its time.

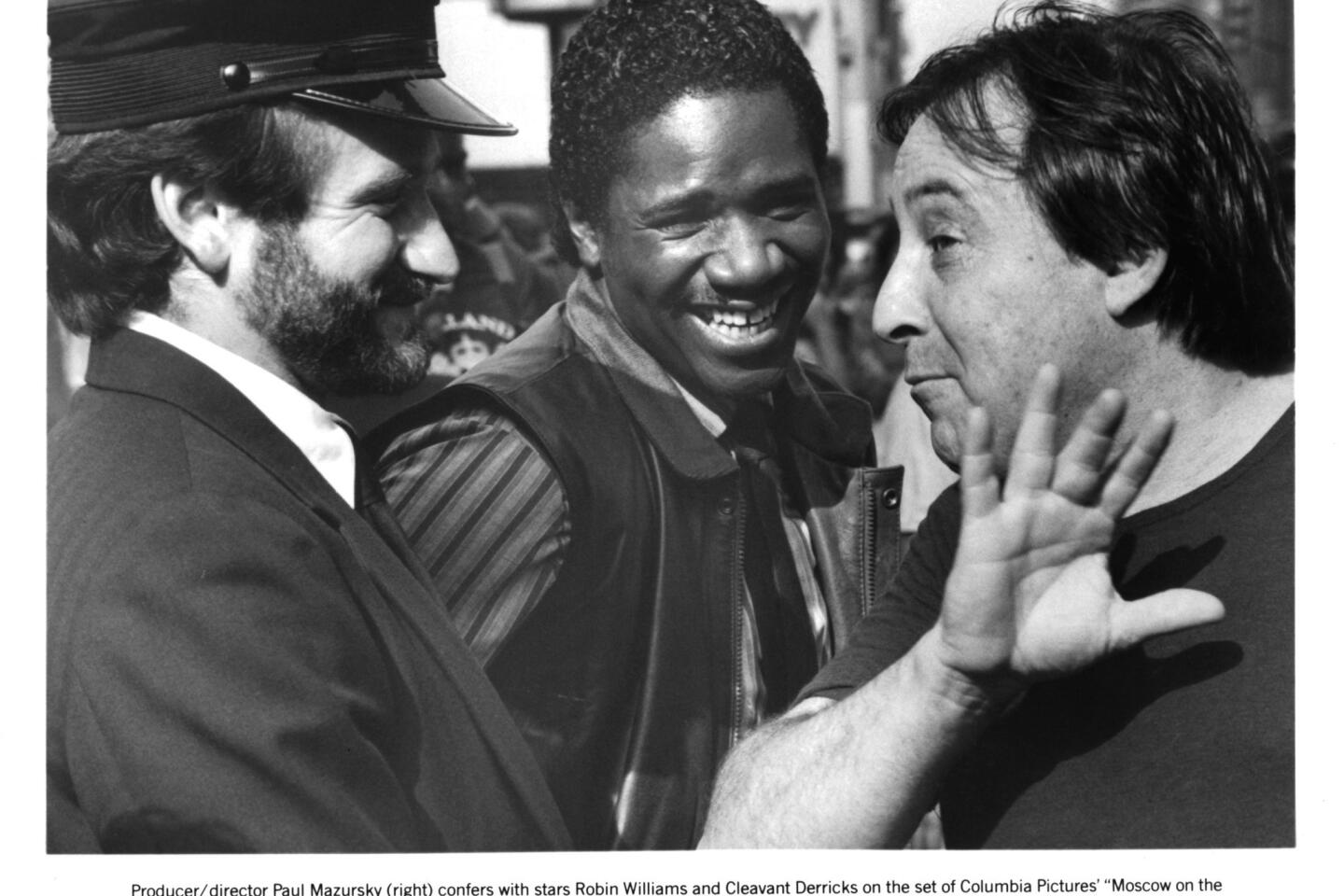

After the show went off the air in 1982, Williams’ reputation for rapid-fire impersonations — not to mention a seemingly endless talent for comic improvisation — landed him a number of high-profile stand-up comedy specials as well as numerous film roles. In “Good Morning, Vietnam” (1987) he played a disc jockey who ruffled feathers with his truth-spewing, quip-cracking ways, while in the animated “Aladdin” (1992), he single-handedly invented the full-bodied voice role as the silver-tongued Genie.

Though now common, the tear-up-the-script style of improvisation practiced by Williams was unusual in major Hollywood productions, and the actor seemed to be able to rewrite the rules by the sheer force of personality — or, as was frequently the case where Williams was concerned — personalities. That talent also landed him a gig co-hosting the Oscars in 1986, a turn that further cemented his A-list status.

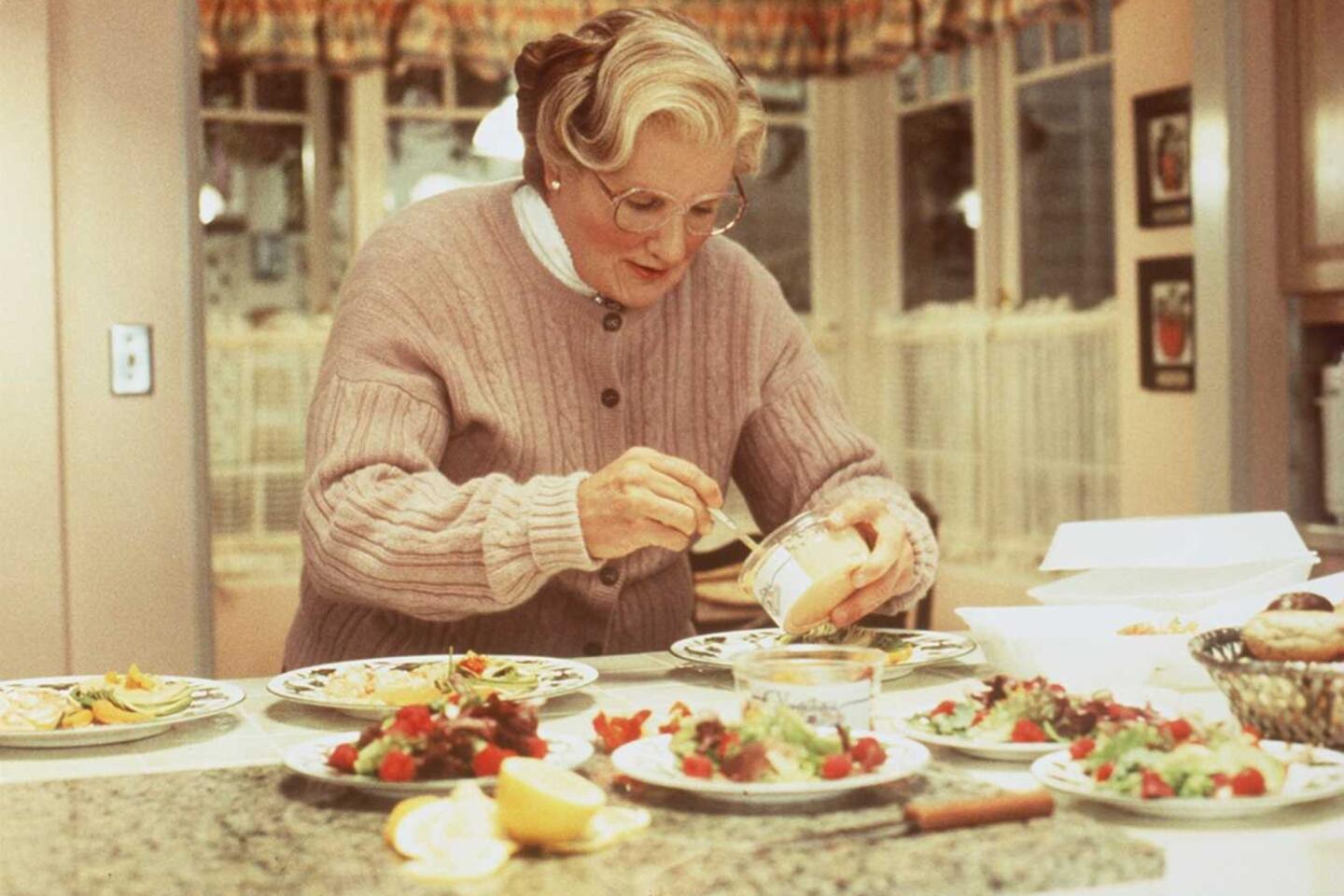

Williams’ protean comedic skills perhaps reached their apex in “Mrs. Doubtfire” (1993), a cross-dressing comedy in which he plays a crusty older nanny and the divorced father who takes on the character to be closer to his children. Though it showcased the kind of on-a-dime personality shifts for which Williams was famous, its madcap conceit was made plausible, many observers believed, by the heartfelt qualities Williams brought to the film.

Indeed, a melancholy undercurrent ran through Williams’ dramatic roles. And there were many of them: He played an unconventional teacher in “Dead Poets Society” (1989), a doctor who tended to the mentally troubled in “Awakenings (1990), a disturbed vagabond in “The Fisher King” (1991) and a psychologist whose wife had died in “Good Will Hunting” (1997).

That last role — in which he famously counseled a hotshot Matt Damon while grappling with his own demons — landed him an Academy Award for supporting actor. He also tried his hand, with generally strong results, in offbeat fantasies, including “Hook” (1991) and “Jumanji” (1995).

Sometimes, Williams’ warmth could appear saccharine. As a doctor dealing with terminally ill patients in “Patch Adams” (1998), Williams was lambasted for mawkishness. It’s “a sad, old show-biz story,” said a critic for New York magazine, “the dulling out, at premium prices, of a once-firebrand talent.”

In the last decade, Williams had turned more to supporting studio roles as well as independent films and even the small screen.

He attempted his first return to network TV with the short-lived sitcom “The Crazy Ones” on CBS last year, and reunited with director Bobcat Goldthwait in the indie black comedy “World’s Greatest Dad” in 2009.

He was nominated for eight Emmys and won two, in 1987 and 1988, for his roles in variety shows.

Further demonstrating his persona-stretching skills, Williams also had well-regarded parts playing presidents — as Dwight Eisenhower in last summer’s hit “Lee Daniels’ The Butler” and as Teddy Roosevelt in the comic franchise “Night at the Museum,” a role he will reprise for the final time when the Ben Stiller film “Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb” opens in theaters this holiday season.

Born in Chicago on July 21, 1951, Robin McLaurin Williams grew up in comfort, the only child of a Ford Motor Co. executive.

“My childhood was very normal,” he told The Times. “Almost hypernormal.”

He liked to describe his mother, Laurie, a Christian Scientist, as a Christian Dior Scientist and said he grew up on a huge estate. “It was miles to the next kid,” he said.

Following his father’s transfer from the Detroit area to San Francisco, Williams completed high school in Marin County and briefly attended what was then Claremont Men’s College before discovering theater. He transferred back to a Bay Area community college, the College of Marin, and ultimately was one of two students accepted into John Houseman’s acting program at the Juilliard School in New York City.

The other was Christopher Reeve, who became a lifelong friend.

In white-face, Williams entertained crowds as a mime outside the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Within a few years, he was doing stand-up at clubs in San Francisco, and then Los Angeles.

One night at the Comedy Store, he was spotted by a relative of “Happy Days” producer Garry Marshall, who ended up catapulting Williams to fame with “Mork & Mindy.”

“I will never forget the day I met him and he stood on his head in my office chair and pretended to drink a glass of water using his finger like a straw,” Marshall said in a statement Monday. “The first season of ‘Mork & Mindy’ I knew immediately that a three-camera format would not be enough to capture Robin and his genius talent. So I hired a fourth camera operator and he just followed Robin. Only Robin. Looking back, four cameras weren’t enough. I should have hired a fifth camera to follow him too.”

Decades after Williams’ first success, he was still trying to define it.

Standing on stage, leaping from voice to voice, from topic to topic, from the absurd to the zany: “It’s Zen-like,” he told the Chicago Tribune. “I don’t know where the stuff comes from. Something kicks in. You’re not in control. That’s what’s scary…”

Late last year, at a filming of the subsequently canceled series “The Crazy Ones,” executive producer and director Jason Winer urged an initially reluctant Williams to let loose and laugh.

And so he did, along with everyone else on the set — for the next half-hour.

“I feel like we’ve made a horrible mistake asking you to laugh,” Winer finally told him.

“I warned you not to uncork me,” Williams replied.

Williams is survived by his wife, Susan Schneider; children Zachary, Zelda and Cody; stepsons Casey and Peter Armusewicz; and half brother McLaurin Smith-Williams.

His previous marriages, to Valerie Velardi and Marsha Garces, ended in divorce.

Twitter: @schawkins, @ZeitchikLAT

Times staff writers Amy Kaufman, David Ng and Ryan Parker contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.