Paul Sylbert, Oscar-winning production designer for ‘Heaven Can Wait,’ dies at 88

- Share via

Paul Sylbert, an Academy Award-winning production designer who created the lighter-than-air atmosphere of God’s waiting room in “Heaven Can Wait” and the white-on-white sterility of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” has died at the age of 88 at his home outside Philadelphia.

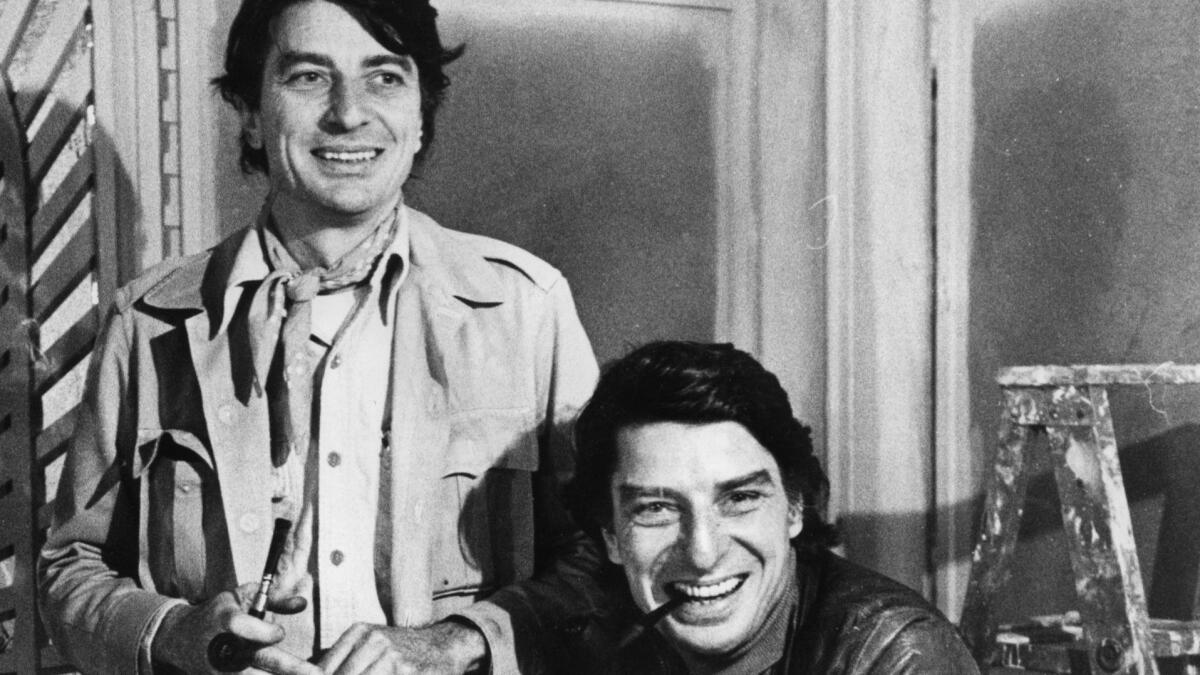

Sylbert and his twin brother, Richard, were go-to players in the 1970s and 1980s when directors like Warren Beatty, Roman Polanski, Robert Benton and John Frankenheimer went looking for someone to capture the visual core of a movie. While Sylbert worked on finding the visual metaphors for “Kramer vs. Kramer” and “Gorky Park,” his brother was helping shape the look of “Chinatown” and “Reds.”

When he was working on “Rush,” the story of two desperate cops hopelessly chasing after an elusive drug dealer, Sylbert spent weeks searching for a neighborhood — preferably on the outskirts of Houston — that would capture the dark edges of the moody 1991 film. He settled on a badly rutted road with ditch water rolling over the curbs and rusted barbed wire in front of the homes. A petroleum plant blotted out the skyline, belching out steam and smoke.

“There’s nothing that looks more like the mouth of hell than a crackling plant when the gas flames are shooting into the air,” he explained to Smithsonian Magazine in a 2008 interview.

Sylbert, who died Saturday, won an Oscar for his work on “Heaven Can Wait” and was nominated for another for his production work with Barbra Streisand on “Prince of Tides.” His other credits include “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” “Kramer vs. Kramer,” “The Drowning Pool,” “Baby Doll” and Alfred Hitchcock’s “The Wrong Man.” His career spanned nearly half a century.

Born in Brooklyn in 1928, Sylbert and his brother were nearly inseparable. They served in the same Army infantry unit in Korea and attended the school of art at Temple University. When Sylbert landed a job at CBS in New York, his brother found work at NBC.

He arrived in Hollywood at a time when the visual fine-tuning of set production work was reasserting itself. If the 1930s and 1940s had taken advantage of the elegance of L.A.’s Art Deco backdrop and the moody side streets that lent themselves to film noir, many of the films of the next two decades had retreated to sound stages or indulgent location shoots, Sylbert said.

“Hollywood fell asleep; the vessel was empty,” Sylbert told The Times in 1990. “They were doing things by rote.”

Which would explain why he went to the trouble to track down furniture covered with cigarette burns for the apartment of the chain-smoking police inspector in “Gorky Park” or why his brother purchased 300 books — handpicked Hemingway novels, Harvard classics, feminist Georgian poets — for a single shot of the bookshelves in a home library in “Without a Trace.”

“Putting a film together is like composing music or painting on a white canvas,” Sylbert told The Times. “Every addition affects the whole.”

Sylbert also designed opera sets for the New York City Opera Company and the summertime Festival of Two Worlds in Spoletto, Italy. He also wrote and directed a feature film, “The Steagle,” the story of a college professor during the Cuban missile crisis trying to live out all of his dreams.

“He was as smart and well-read as anyone I have ever come in contact with, and all who knew him respected him,” said Hawk Koch, a film producer who worked with Sylbert on “Heaven Can Wait” and “Gorky Park.”

At the time of his death, he was writing a book on the craft of production design, his wife, Jeanette, said. She said he also was teaching film courses at Temple and the University of Pennsylvania.

“He was a wonderful man who believed in fair play, civility and courage, and was unafraid to say it like it was,” his wife said.

In addition to his wife, he is survived by two children, Olivia and Christian. He was preceded in death by another child, Christopher. His brother died in 2002.

twitter: @stephenmarble

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.