Kim Fowley dies at 75; music producer created, managed the Runaways

- Share via

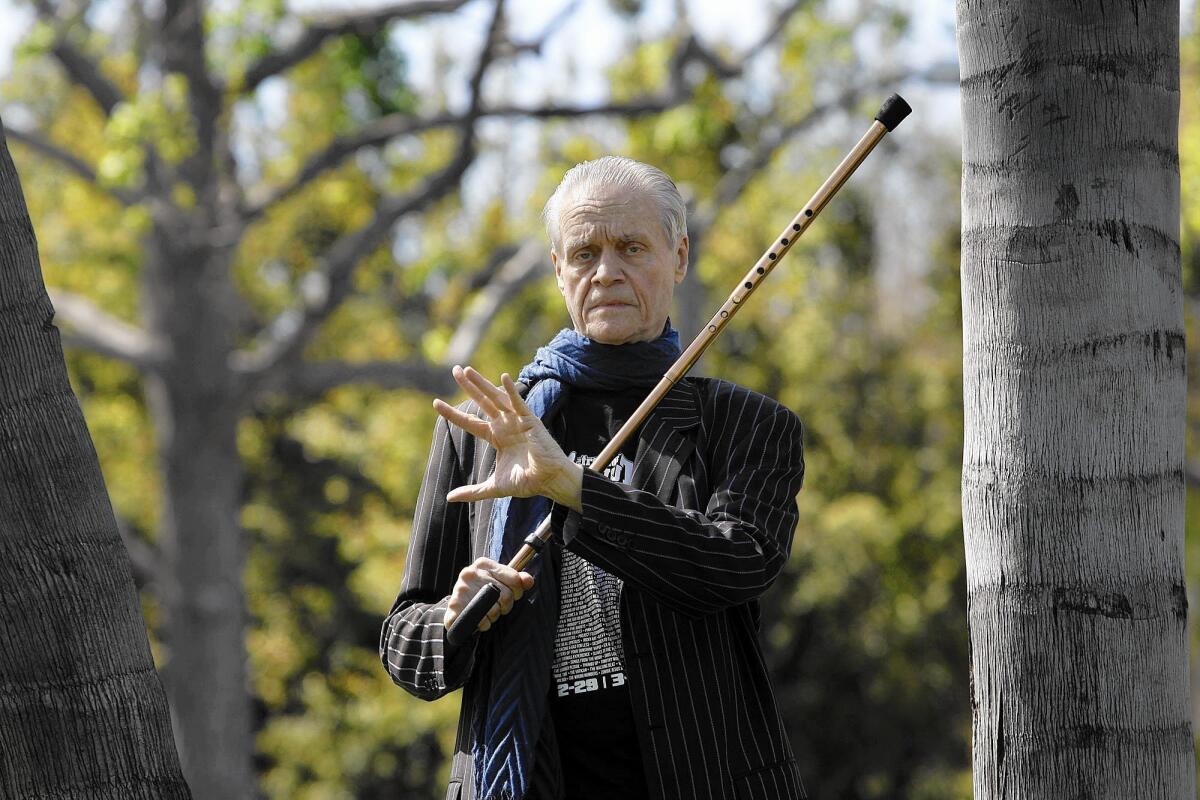

Kim Fowley, the mercurial and eccentric music producer and Svengali who created and managed the all-female rock group the Runaways in the 1970s, died Thursday after a long battle with bladder cancer. He was 75.

Fowley’s longtime friend, author-historian Harvey Kubernik, confirmed his death.

Fowley had been periodically posting updates from his bed on his Facebook page, many featuring his wife, Kara Wright. Last year Fowley moved from the hospital to the Los Angeles home of Runaways founding member Cherie Currie, who told Billboard in September that after consulting with Wright about his health, “We agreed a change of environment was what he needed. It’s draining, yes, but I’ll always step up. It’s who I am.”

“I love Kim. I really do,” she said at that time. “After everything I went through as a kid with him, I ended up becoming a mom and realized it was difficult for a man in his 30s to deal with five teenage girls. He’s a friend I admire who needed help, and I could be there for him.”

He subsequently moved with Wright, whom he married in September, to a residence in West Hollywood, where he died.

Fowley’s memoir, “Lord of Garbage,” was published in 2013, and Times book critic David L. Ulin wrote that it “may be the weirdest rock ‘n’ roll autobiography since ... well, I can’t think of what.”

Fowley was at least as colorful as any of the musicians he worked with going back to the 1960s in L.A., where a vibrant rock music scene attracted many of the most creative and most idiosyncratic characters imaginable.

“Kim Fowley is a big loss to me,” Steve Van Zandt, guitarist of Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band and host of Sirius XM satellite radio’s channel Little Steven’s Underground Garage, said in a statement Thursday. “A good friend. One of a kind. He’d been everywhere, done everything, knew everybody.

“He was working in the Underground Garage until last week,” Van Zandt said. “We should all have as full a life. I wanted DJs that could tell stories first person. He was the ultimate realization of that concept. Rock Gypsy DNA. Reinventing himself whenever he felt restless. Which was always. One of the great characters of all time. Irreplaceable.”

Fowley, born July 21, 1939, in Los Angeles to actor-parents Douglas Fowley and Shelby Payne, scored his first chart success producing the 1960 single “Cherry Pie” for Gary Paxton and Skip Battin, aka Skip & Flip. Fowley continued working with Paxton when they created the Hollywood Argyles band, which charted a No. 1 hit, also in 1960, with the song “Alley Oop.”

The man known for his pasty white skin, pale blue eyes and slicked back hair — punk rock godfather Iggy Pop once described him as looking “physically frail, a lot like Boris Karloff’s Frankenstein”— became a regular at clubs on the Sunset Strip as music exploded and continued to evolve over the next several decades.

He went on to write or produce songs for a range of musicians, including the Byrds, the Beach Boys, Frank Zappa & the Mothers of Invention, Gene Vincent, Helen Reddy and Warren Zevon. He also recorded a string of solo albums under his own name.

Fowley traveled to England early on to check into the British rock scene that was igniting but hadn’t yet invaded the U.S.

“One of the first who smelt something going on in ’63 and came to England,” Andrew Loog Oldham, the Rolling Stones’ first producer and manager, said Thursday. He praised Fowley as “a leader of that American brigade and a forever part of American music.”

Fowley turned up in September 1969 to introduce John Lennon’s solo appearance at the Toronto Rock and Roll Festival, less than seven months before the Beatles formally disbanded. It was the public debut of the Plastic Ono Band, which became Lennon’s primary musical outlet after the Beatles.

In the mid-’70s, Fowley gathered a group of five teenage girls and created a then-rare example of an all-female punk-rock band in which all of the members played the instruments and sang.

Although initially viewed as a novelty, the Runaways included three future solo rock stars in Currie, Joan Jett and Lita Ford, thanks to Fowley’s eye and ear for young talent.

He praised some parts of Floria Sigismondi’s 2010 feature film “The Runaways” but complained about being painted as a villain. “It was a nighttime soap opera, with some rock music in it,” he said in 2012. “It was not, not, NOT, in bold letters, it was not the Runaways’ story.”

A 2012 documentary called “The Sunset Strip” again put the spotlight on Fowley, who summed up the scene he relished, saying, “The Sunset Strip is a civilization for the brokenhearted, the mistreated, the overlooked, the underloved and the doomed.”

Although he never abandoned his passion for music, he shifted his focus from recordings to film later in life, making movies such as 2011’s “Black Room Doom” about an all-female band using that name and delving into their sexual appetites as they played out in L.A. fetish clubs. Fowley touted his film as “a female ‘Spinal Tap’ on a female ‘Jackass’ level.”

Fowley also often boasted that he would do things others feared to attempt.

“One of my secrets, throughout this career that I’ve had,” he told The Times in 2012 at a Hollywood strip-mall recording studio where he was working at the time, “is [that] the word ‘no’ does not exist in my vocabulary.”

Fowley, who often referred to himself by name, remained a revered figure as a songwriter, co-writing several songs on L.A. musician Ariel Pink’s 2014 album, “Pom Pom.”

Fowley remained a controversial figure because of his relationships with adoring — and sometimes less-than-adoring — young women, which created rocky times during his mentoring of the Runaways and other aspiring musicians who came his way in their wake.

“I’m a horrible human being with a heart of gold,” he said in 2012. “I’m the worst, horrifying but lovely. I’m a bad guy who does nice things.”

Fowley is survived by Wright.

Twitter: @RandyLewis2

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.