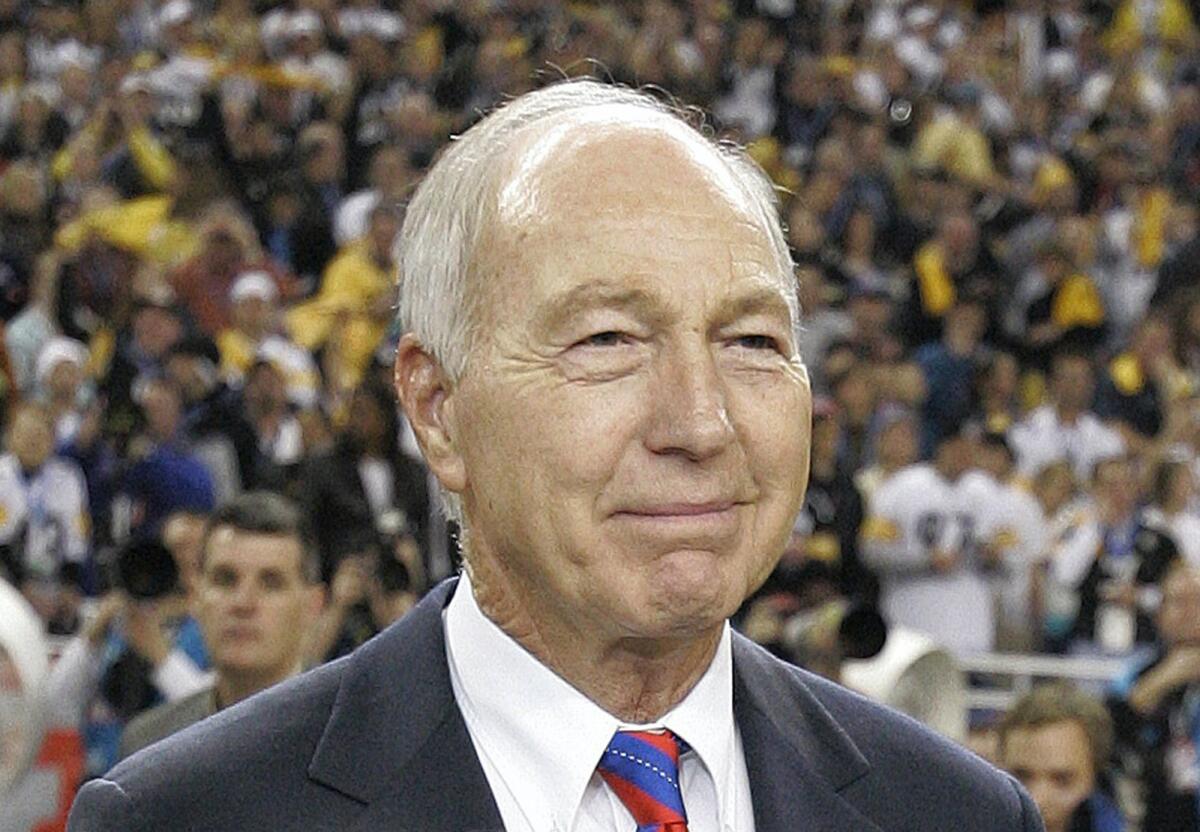

Bart Starr, Packers legend who led team to first Super Bowl titles, dies at 85

- Share via

The greatness of Bart Starr almost never happened.

The 17th-round draft choice nearly walked away from the Green Bay Packers — a franchise he would quarterback to five league championships and victories in the first two Super Bowls — before his career even got off the ground.

“Bart didn’t think he was going to make the team, literally was going to leave training camp, and [coach Vince] Lombardi talked him back into staying,” said Joe Horrigan, executive director and historian of the Pro Football Hall of Fame. “It was the little town that couldn’t, the coach who had been rejected, and the quarterback who no one thought could be who he was.

“If you were making a movie, and you put all those ingredients in it, you shook it up and poured it out, it would be the Green Bay Packers and Bart Starr would have the leading role.”

Starr, who had been in failing health since suffering a stroke in 2014, died Sunday in Birmingham, Ala., where he was born and raised, the Packers announced. He was 85.

“The Packers Family was saddened today to learn of the passing of Bart Starr,” said Packers President and CEO Mark Murphy. “A champion on and off the field, Bart epitomized class and was beloved by generations of Packers fans. A clutch player who led his team to five NFL titles, Bart could still fill Lambeau Field with electricity decades later during his many visits. Our thoughts and prayers go out to Cherry and the entire Starr family.”

Born Bryan Bartlett Starr on Jan. 9, 1934, Starr became an all-star quarterback in Montgomery at Sidney Lanier High School, then accepted a scholarship at the University of Alabama, where his career stalled.

The Packers, who traced their history in the National Football League to 1921 and had won six league championships under legendary founder-coach Curly Lambeau, were a team in disarray when Starr joined them in 1956. They hadn’t had a winning season in nine years and were on their third coach — soon to be fourth, then fifth — in that span.

Starr certainly wasn’t viewed as a franchise savior. That he was in the NFL at all was surprising, since he had played little in his junior and senior seasons at Alabama, thanks to a back injury, then a coaching change and a new offensive system. But Johnny Dee, Alabama’s basketball coach who had helped out with the football team, thought Starr might have possibilities and recommended him to Jack Vainisi, his former Notre Dame classmate and director of player personnel at Green Bay. Vainisi took a chance, drafting him as a backup.

“It was obvious they thought I was not going to stay,” Starr told The Times in 1987. “In our first photo session, they gave me No. 42. [Quarterback numbers typically are single digits through the teens.] On my first bubble-gum card, I was No. 42.”

Still, a chance is a chance. “I would not have been disappointed if I was the 40th pick,” Starr said. “I just wanted the opportunity. ... I wanted to play badly.”

That’s precisely how the Packers played for the next three seasons, hitting a low in 1958 with a 1-10-1 record. Starr, by then wearing the No. 15 that would later be retired in his honor, had played little as a rookie, then shared time with the veteran Vito “Babe” Parilli the next two seasons.

Then Vince Lombardi hit Green Bay, and Starr, the Packers and the state of Wisconsin would never be the same. It didn’t happen immediately, of course — “He didn’t have any confidence in me,” Starr said of Lombardi, who was in his first head-coaching assignment. “I hadn’t shown him anything. I had to earn his respect.” — but eventually Lombardi put his trust in Starr and great things happened.

“Bart Starr was smart, and he was the vehicle into which Lombardi poured all of his knowledge,” David Maraniss, author of “When Pride Still Mattered: A Life of Vince Lombardi,” told The Times on Sunday.

“Starr took it in and became Lombardi on the field. That was important because Lombardi was a great coach on Monday through Saturday, but he was pretty much helpless on Sundays. He didn’t do much. Starr was almost the coach for the offense on Sundays.”

Lombardi’s later assessment of Starr? “Bart Starr stands for what the game of football stands for: courage, stamina and coordinated efficiency.... The noblest form of leadership is by example, and that is what Bart Starr is about.”

Lombardi was a tough taskmaster — dictator, some would say — but his Packers were a free-spirited bunch, receiver Max McGee and running back Paul Hornung the chief merrymakers, and the quietly efficient Starr turned out to be just the leavening presence Lombardi needed. Starr was so soft-spoken, in fact, that in one of his early starts, when he told a yakking McGee to “Hush up!” in the huddle, the team broke into laughter and had to call time out.

Hall of Fame quarterback Steve Young, whose NFL career began 14 years after Starr had retired, said the Packers legend set the standard for the way players should carry themselves.

“It’s tough to find inspiring, great human beings,” Young said Sunday. “And then when you find one that’s actually an iconic, hall-of-fame athlete, it’s very unusual. He had an impact on me, even with the age difference, because I always could use him as an example of somebody who could be great, but then could be kind.

“He didn’t have to use everything as a weapon. Fame was never a weapon for him. That iconic stature was never a reason to not be gracious.”

Echoed Hall of Fame receiver James Lofton, who began his career with the Packers seven years after Starr retired: “There was a grace and dignity about him that you just don’t find in too many other people.”

There was little indication early on that Starr would become a star. He wasn’t big, he wasn’t fast, and he didn’t have a strong arm. He had a mind that soaked up football theory, though — he was quick to determine an opponent’s weakness, then attack it — and he worked hard to correct his physical deficiencies. His passes weren’t long but they were on the money.

And he was tough. Guard Jerry Kramer recalled for Investor’s Business Daily in 2011 how Chicago Bears linebacker Bill George once tackled Starr high, splitting his lip up to his nose, then taunting the bleeding quarterback about being soft. According to Kramer, Starr pointed to George and said, “Bill George, we’re coming after you!”

Then, Kramer said, “Bart took us down the field and we scored. Then he gets stitched up, never misses a play, we win the ballgame and Bart Starr was proven to me.”

Said Starr often, “You must have a fanatical desire for excellence. Coach Lombardi stressed ... that being good is not good enough. He ... believed that through chasing perfection, we could achieve excellence.”

Starr got the message. Before he was through as a player, he had set passing records, was named the league’s most valuable player and twice was MVP of the Super Bowl. He was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame on the first ballot.

The Packers’ signature game under Lombardi was the NFL title game on New Year’s Eve 1967 against the Dallas Cowboys, the game known as “the Ice Bowl.” The Packers were going for their third consecutive championship, and Starr had the leading role.

It was 13 degrees below zero, with a wind-chill factor of minus 49, at game time in Green Bay and conditions worsened as the game wore on. Trailing 17-14 with five minutes remaining, Green Bay had the ball at its own 32-yard line. “This is it,” Starr told his team. “Let’s get it done.”

He took the Packers downfield and, with 16 seconds left and the ball on the Dallas one-yard line, called the team’s last timeout. By then the field was a sheet of ice. What to do? Pass or run? “Run it,” Lombardi said, “and let’s get the hell out of here.”

Starr called for a handoff to fullback Chuck Mercein but instead kept the ball himself, following Kramer and center Ken Bowman, who had team-blocked tackle Jethro Pugh, into the end zone, and the Packers won 21-17.

The Packers went on to beat the AFL’s Oakland Raiders in Super Bowl II, then Lombardi stepped down as coach and the dynasty was over. Starr played for three more seasons, sat out the 1971 season recuperating from shoulder surgery and was hoping to come back the next year. He couldn’t lift his arm to throw, however, and spent the ’72 season as quarterback coach and play caller for Dan Devine.

Devine, highly successful as a college coach, was a bust in Green Bay and soon Packer fans were calling for Starr to replace him, bumper stickers pleading, “Bring Back Bart.” After a dismal season-ending loss to Atlanta in December 1974, Devine skipped off to Notre Dame and, two days before Christmas, Starr was hired, practically by acclaim, to replace him.

“It may take a while, but it is my unequivocal pledge to give this organization a fresh start,” he said at the time.

As revered as he had been as a player, however, he couldn’t find success as a coach, perhaps trying too hard to be the next Lombardi. In very un-Starr-like fashion, he ripped former Packers who’d gone on to other teams, praised players one day, then put them on waivers the next, eventually winding up with a divided locker room.

He drew the wrath of the league for running supposedly secret unsanctioned tryout camps and the wrath of the fans when he lost a high draft choice as punishment. He feuded with the media, at one point trying to bar a sportswriter from covering Packers games. Most seriously, though, his Packers lost, and continued losing, and by the end of his tenure, the bumper stickers were reading, “Send Starr Far.”

Because he was Starr, though, the team’s executive committee kept him on for nine seasons, only one of which was profitable. The Packers posted a 5-3-1 record and made the playoffs in strike-interrupted 1982. Starr finished his coaching career with a 52-76-3 record.

Sign up for our daily sports newsletter »

Years later, he said taking the coaching job had been a mistake. “I hadn’t trained to be a coach,” he told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. “Being an assistant under a Coach Lombardi or a Tom Landry ... that prepares you to do a better job when you become a coach. I hadn’t received that training. It showed.”

Starr’s legacy as a player, though, remains safe among Packer fans. At halftime of the Packers’ home opener in 2013, players from the Lombardi era were introduced. All were warmly received but when Starr was announced, last, Lambeau Field erupted, his ovation doubling those of the other Packers heroes.

Kupper is a Times contributing writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.