L.A.’s underground music scene thrives in buildings that often lack basic safety features, with little scrutiny from the city

- Share via

Scores of mostly young people followed the digital-age equivalent of treasure maps to faceless warehouses and old storefronts in downtown Los Angeles, a hotbed of the city’s underground music scene.

Entrée to the makeshift nightclubs that take shape in the buildings required message exchanges or security codes, parceled out through websites and Facebook pages.

Typically, the locations were not revealed to the ticket buyers until shortly before the doors opened.

The hosts of the events collected cover charges of up to $20, sold alcohol at premium prices and kept the music going well into the early morning hours.

And little or none of that was legal — or safe for the revelers who crowded into spaces that sometimes lacked sprinklers, well-lighted exits and other safety features found at legitimate performance halls.

The business of these illicit concerts and music parties has thrived for years in L.A. and elsewhere, despite operating in violation of fire and building ordinances.

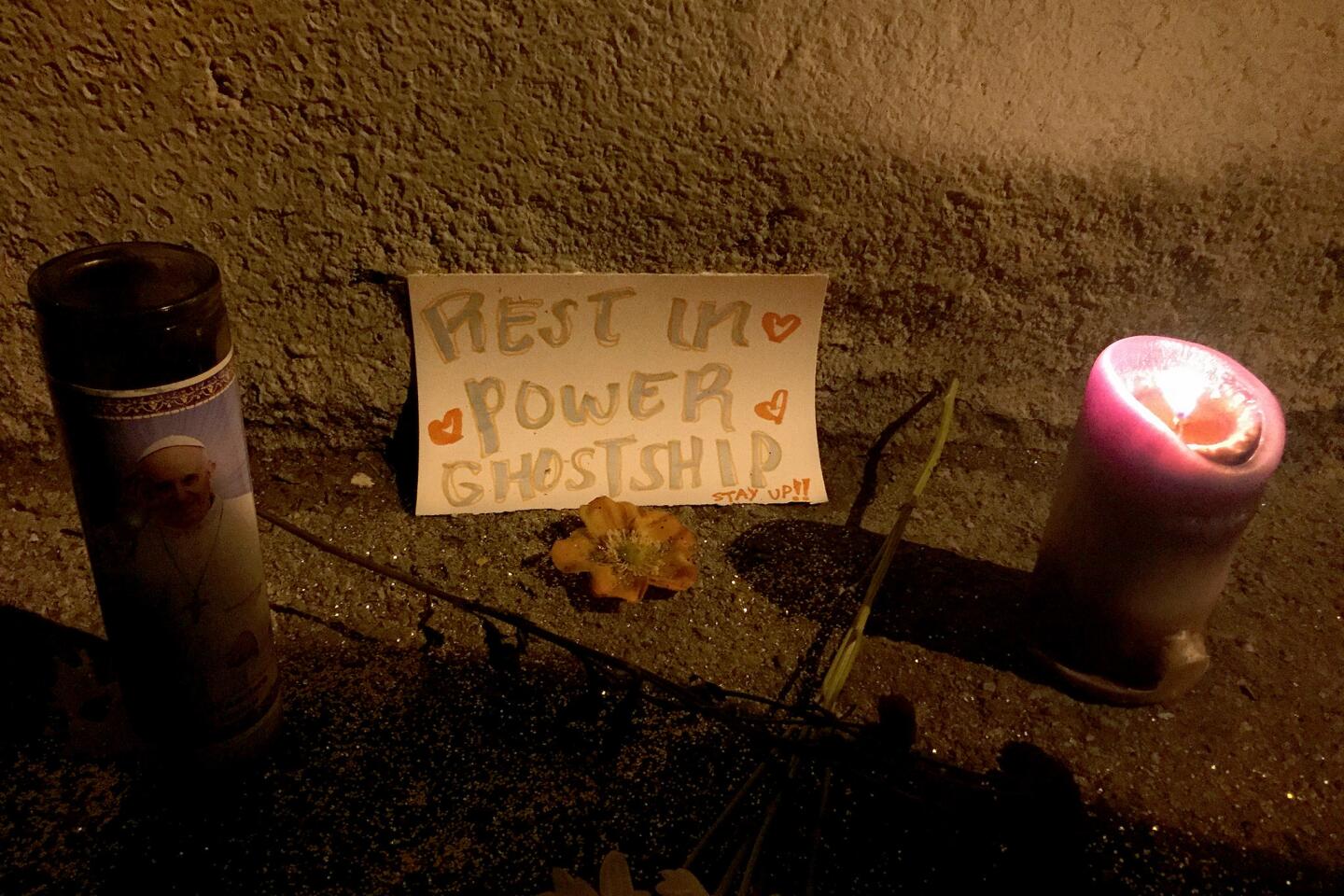

The events generated little scrutiny from public officials until earlier this month, when the deadliest fire in modern California history cast a tragic spotlight on the dangers. Flames swept through the Ghost Ship, an illegally converted warehouse in Oakland where a concert was underway. Thirty-six people died.

Los Angeles’ record of cracking down on such concerts has been sporadic and infrequent at best, according to city data and interviews.

The underground clubs present shows within blocks of L.A. Fire Department stations, but the agency has cited fewer than 10 of them in the last three years, spokesman Peter Sanders said.

The city Building and Safety Department said its inspectors do not take the initiative to look for violations in areas known for the music pop-ups, such as downtown’s industrial and fashion districts.

Rather, the department waits for someone to file a complaint about a specific address, said spokesman David Lara.

A Times analysis of three years of department records found fewer than 25 cases — an average of about eight annually — in which the agency investigated a building owner because of complaints of concerts or music parties.

Los Angeles has not seen a catastrophe on the scale of the Ghost Ship. But experts said the city is at risk given the size of its music scene and the large number of warehouses and other properties whose owners are willing to host concerts.

“We’ve just been lucky,” said Jean M. Daly, a former prosecutor for the L.A. County and San Francisco district attorney offices who specialized in fire-related cases. “We’re ripe for that situation.”

Robert L. Rowe, a former fire marshal for the city of Downey, said warehouses in particular are not designed for large assemblies of music fans. For starters, he said, they generally have too few exits to evacuate people in a fire.

“That’s a disaster waiting to happen,” Rowe said.

On a recent weekend, reporters for The Times attended five underground performances downtown. All were held in buildings that had no permits to operate as a music venue, according to city records and interviews.

The reporters had little trouble finding websites and Facebook posts that advertised the so-called “do it yourself” events, but they could not pierce the wall of secrecy around all of them.

Promoters of some performances did not respond to the reporters’ requests for tickets — or codes used to get them — and so the addresses of those venues could not be obtained.

One Friday night concert was staged in a warehouse and manufacturing building on Ceres Avenue downtown. The location was disclosed to attendees who received a code from the promoter. Admission was $20 and a bouncer checked IDs at the door.

By 1 a.m., about 200 people had filed into a high-ceilinged room to hear D.J. Prins Thomas. The space was bathed in a pink haze generated by a smoke machine and laser display. There were no sprinklers.

A 20-something couple, Ellyn Maranda and Delwin Soren, who were new to L.A. from Texas, said friends led them to the event. They said they preferred underground clubs because the music was better and more varied.

“I feel safe,” said Maranda. “I worry that people will think all warehouses are smokestacks. A lot of warehouses and creative spaces are run really well.”

Soren said a crackdown on the scene could backfire.

“If it’s pushed more underground, it’s only going to make it more dangerous,” he said.

On the same night, a performance took place in a warehouse on East 7th Place. Attendees had to RSVP through a website. The fast-paced techno music played in a second-floor room, up a dim stairwell and down a long corridor.

At the entry, a woman with an iPad checked everyone’s name against a list. A wooden table piled with bottles of liquor served as the cash-only bar.

Sprinklers hung from the ceiling, but there were limited exits and the room was dense with cigarette smoke. Smoldering cigarette butts were tossed on the floor.

Less than two miles away, an underground benefit concert for victims of the Ghost Ship fire drew dozens of people to an aging fashion-industry storefront on South Los Angeles Street.

The entrance was off a back alley, where donations of $10 were collected. Inside, attendees sat on the floor before the stage, a silver disco ball overhead, and listened meditatively to a set by Elaine Carey and Mitchell Brown. Goth electronic music followed.

There were no signs of sprinklers, fire extinguishers or a second exit. Attempts to interview a man listed in public records as an owner of the building were unsuccessful.

A firm named Restless Nites promoted the benefit. A principal in the firm, Eli Glad, said it takes “extremely seriously” the safety issues spotlighted by the Ghost Ship catastrophe. On the other hand, he said, the underground circuit “is not going to go away.

“Parties have been happening forever, whether they’re in legal spaces or not.”

The next night brought another round of events, including a second one at the 7th Place warehouse, a recurring party called Joy Tactics. DJs pumped out techno and deep house music, and mixed drinks sold for $8.

In the audience of 60 were two organizers of the event — Martin Santiago and Ryan Sandoval. “It’s cool because it’s very small venues, so most of the time you’re close to the speakers and you see the artists playing right in front of you,” said Sandoval, 24.

Santiago, 23, said they focus on safety when selecting a location for the parties. “We definitely vet the venue,” he said, describing the warehouse as “a solid place for people to come and congregate.”

One of the performers who died at the Ghost Ship, Chelsea Faith Dolan, who made music under the name Cherushii, headlined an earlier Joy Tactics event, Sandoval said. On a table at the 7th Place party sat a donation jar for her and the others who died in Oakland.

The owners or managers of the buildings visited by The Times variously declined to comment, could not be reached for an interview, or said they were unaware of any illegal use of their property.

The manager of the Ceres Avenue building, Gary Herman Sr., said he and the owners did not know their tenant had held concerts there. He said the tenant would be evicted if it happened again.

“He does not have occupancy for that use,” Herman said. “And besides that, it’s illegal.”

The tenant did not respond to interview requests.

Lara, the Building and Safety Department spokesman, said warehouse and storefront owners could apply for a permit to host concerts, but would not receive one without first upgrading their properties to meet the safety standards imposed on traditional music venues.

That could mean installing sprinklers, adding exits and providing disabled access, among other improvements, which likely would render the undertaking prohibitively expensive.

Music promoters say money is also a reason that many underground acts do not perform at established concert houses. They usually do not have a large enough following of paying fans to land a booking at a profit-driven club.

“We deal with extremely unknown artists,” said Britt Brown, who, along with his ex-wife, runs the L.A.-based 100% Silk, a record label for three of the acts that performed at the Ghost Ship the night of the fire. “Nobody’s making any money off this.”

Last November, Brown said, 100% Silk hosted a music event at a warehouse and commercial building on McGarry Street in downtown L.A. It featured one of the Ghost Ship performers, Golden Donna.

The structure has no permit for concert gatherings, according to the Building and Safety Department.

Peter Schwartz, an attorney for the owners, said his clients had no idea music performances were occurring in the building, which is divided into numerous units.

“We’re concerned that it’s happening,” Schwartz said. “The landlord doesn’t approve of it.” He said the owners were taking steps to ensure concerts would not be held there again.

Brown downplayed 100% Silk’s role in the McGarry and Ghost Ship events.

“We connect artists to people we may know who have access to a space,” he said. “We’re connecting people via email or posting a flier on a Facebook. … Our involvement is like ‘hosting’ the flier.”

Brown said he did not know the McGarry building had no permit for music performances. “It’s a big, concrete building,” he said. “I think it’s safe.”

Times staff writer Ruben Vives and Times researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

[email protected] | @pringlelatimes

[email protected] | @AgrawalNina

[email protected] | @makedaeaster

MORE ON THE GHOST SHIP FIRE

Family of 20-year-old brings first suit in Oakland warehouse fire

Officials crack down on San Diego art venues following Oakland fire

The Ghost Ship fire was ‘a matter of benign neglect.’ It’s not the only one

Amid Ghost Ship’s enchanting disorder lurked danger and the seeds of disaster

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.