Chino Hills artist Abel Izaguirre creates tiny tributes to his old home: South L.A.

- Share via

To those new to street art, there are aspects of Abel Izaguirre’s empire that might surprise and alarm. Many of the 37-year-old Chino Hills artist’s designs are callous celebrations of guns and dice, turf and cognac -- of the gangster life that defines and afflicts so much of the metropolitan area. They appear on everything from shoes to skateboards to, by special request, caskets.

On one of Izaguirre’s T-shirts, Ben Franklin -- Founding Father, inventor of the bifocal, et cetera -- points a Beretta pistol into the viewer’s eyes. On another, a skeleton’s hands are clasped in prayer in front of an ominous vision of the L.A. skyline. “Perdoname por mi vida loca,” that one says. “Forgive me for my crazy life.”

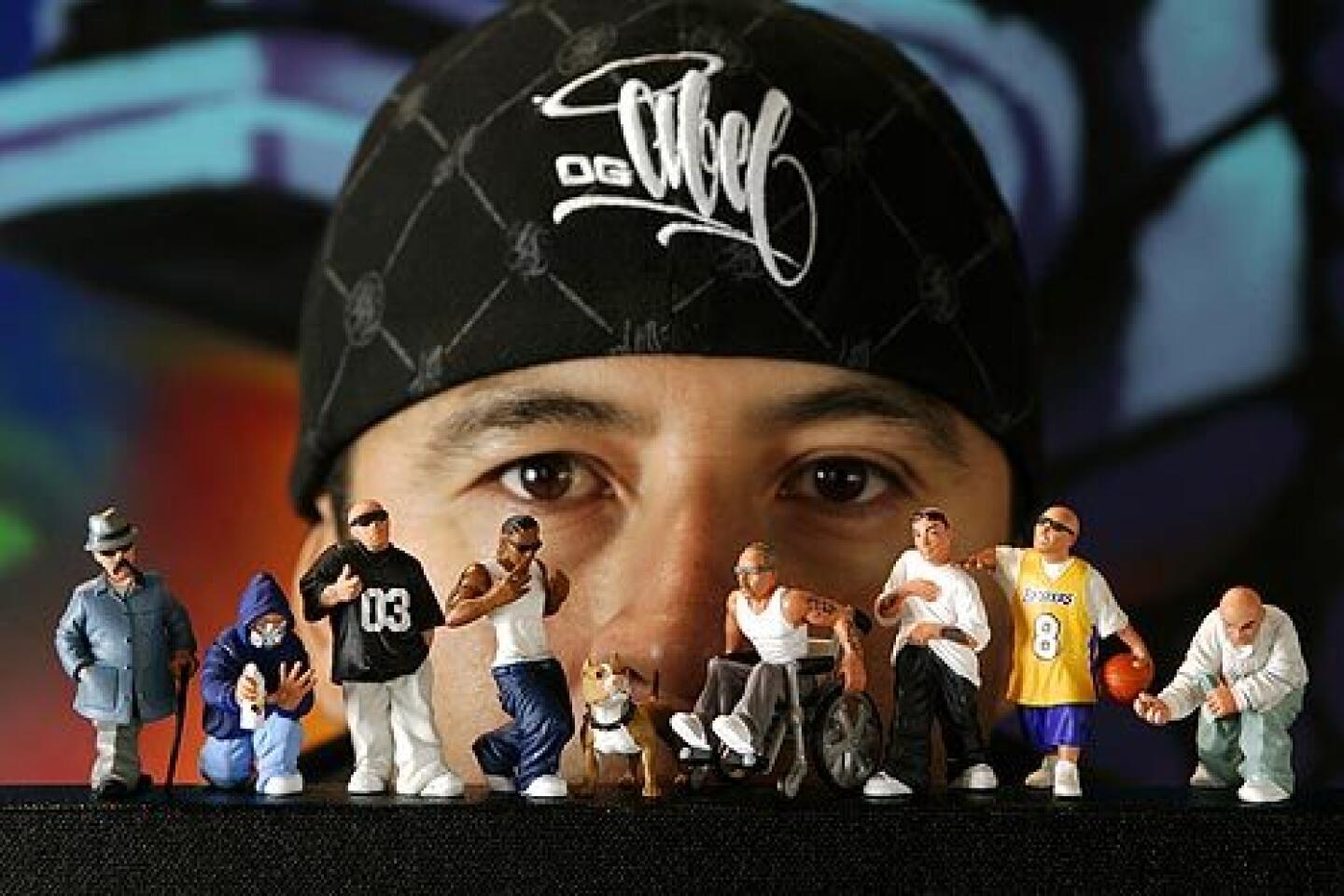

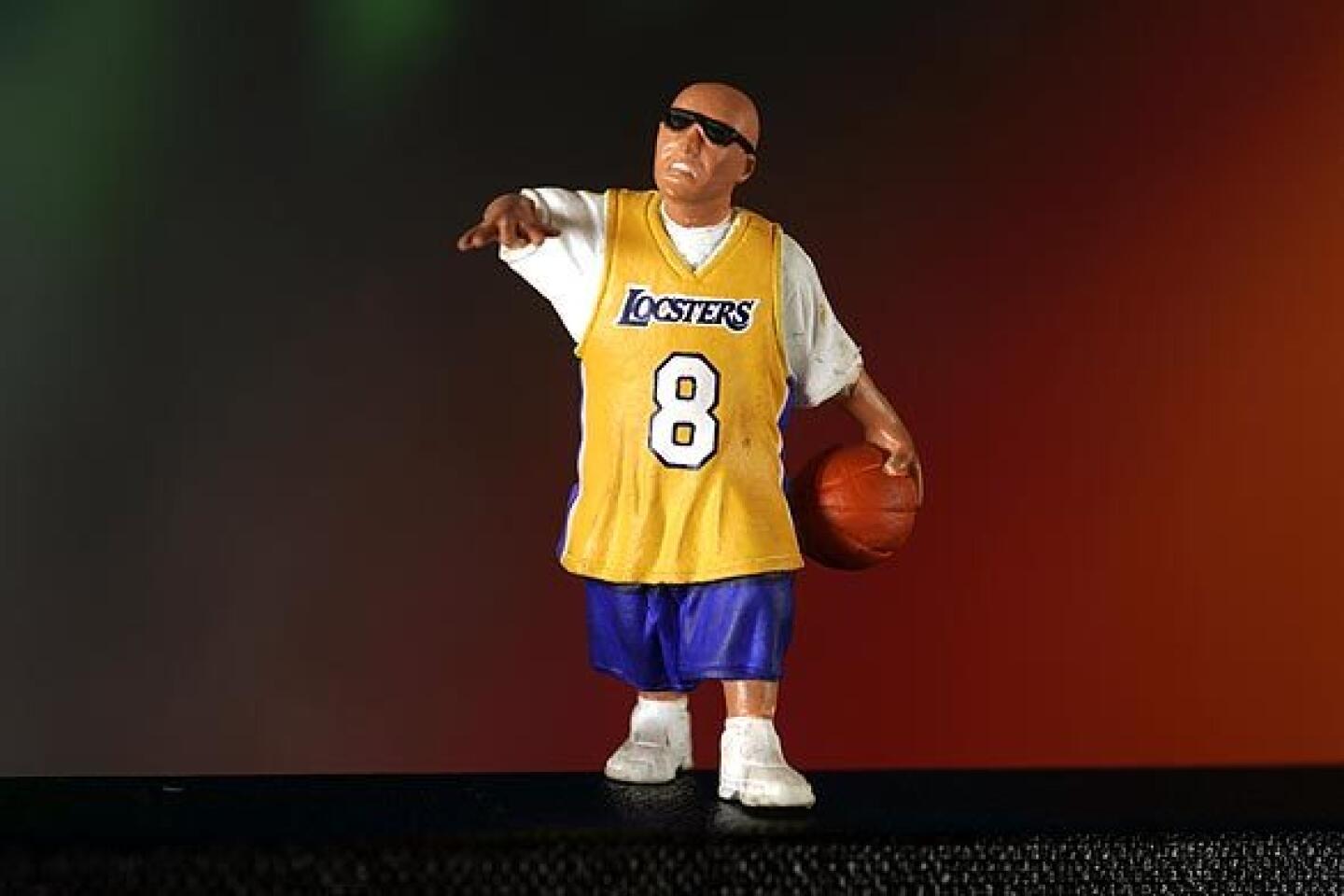

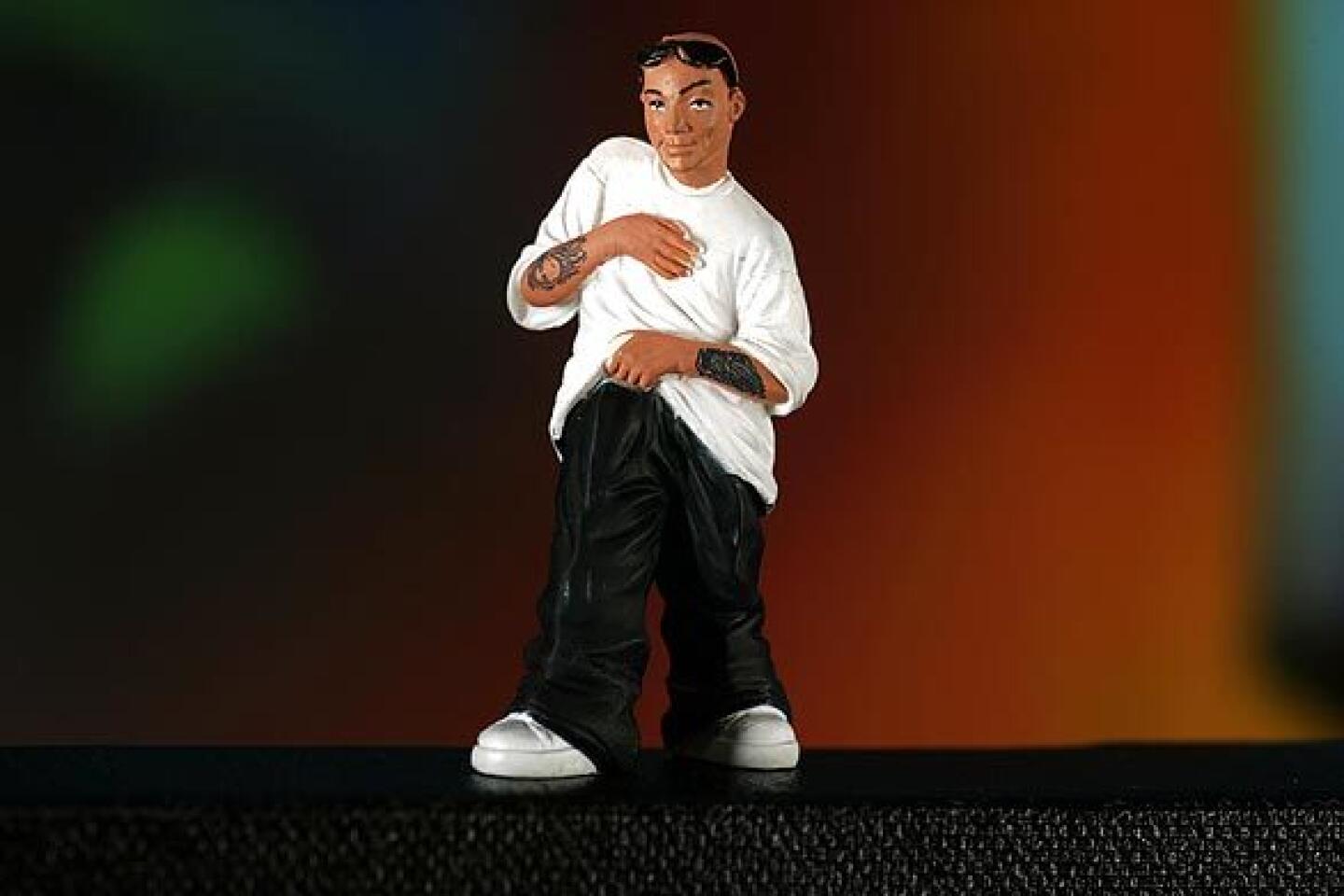

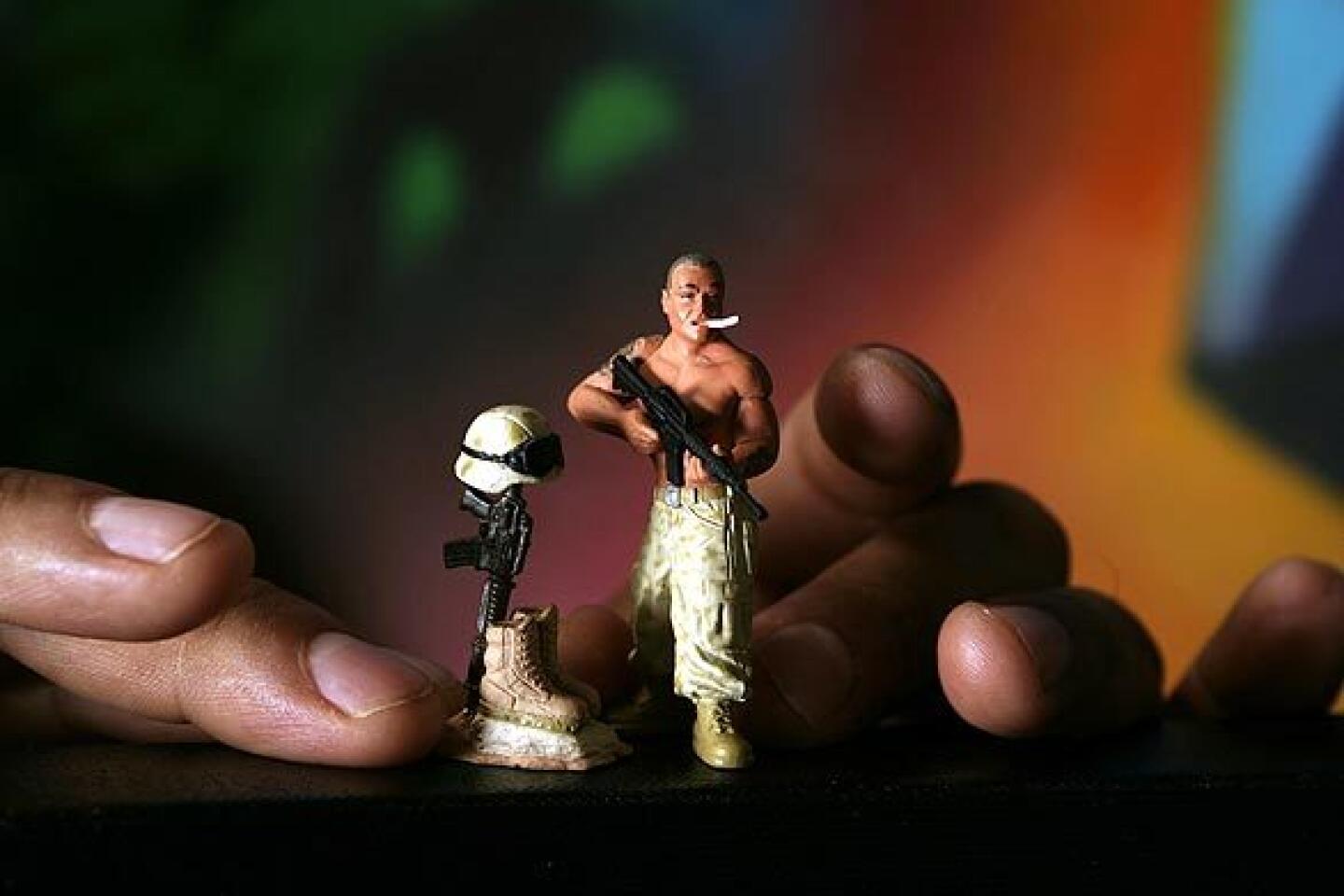

One piece of Izaguirre’s portfolio stands out. They are toys, 2-inch-tall figurines marketed to children, and they comprise a startlingly graphic and cynical depiction of urban Los Angeles. They’re called Locsters.

One, named “Vago” -- that’s Spanish for lazy bum, basically -- has been forced to his knees during a police raid. Smirking, his hands are clasped behind his head, revealing the words “TUFF LUCK” tattooed in gothic print on his forearms.

There is “Bat Boy,” named for the baseball bat in his hand; it’s unclear what the bat is for, but from the look on his face, it isn’t baseball.

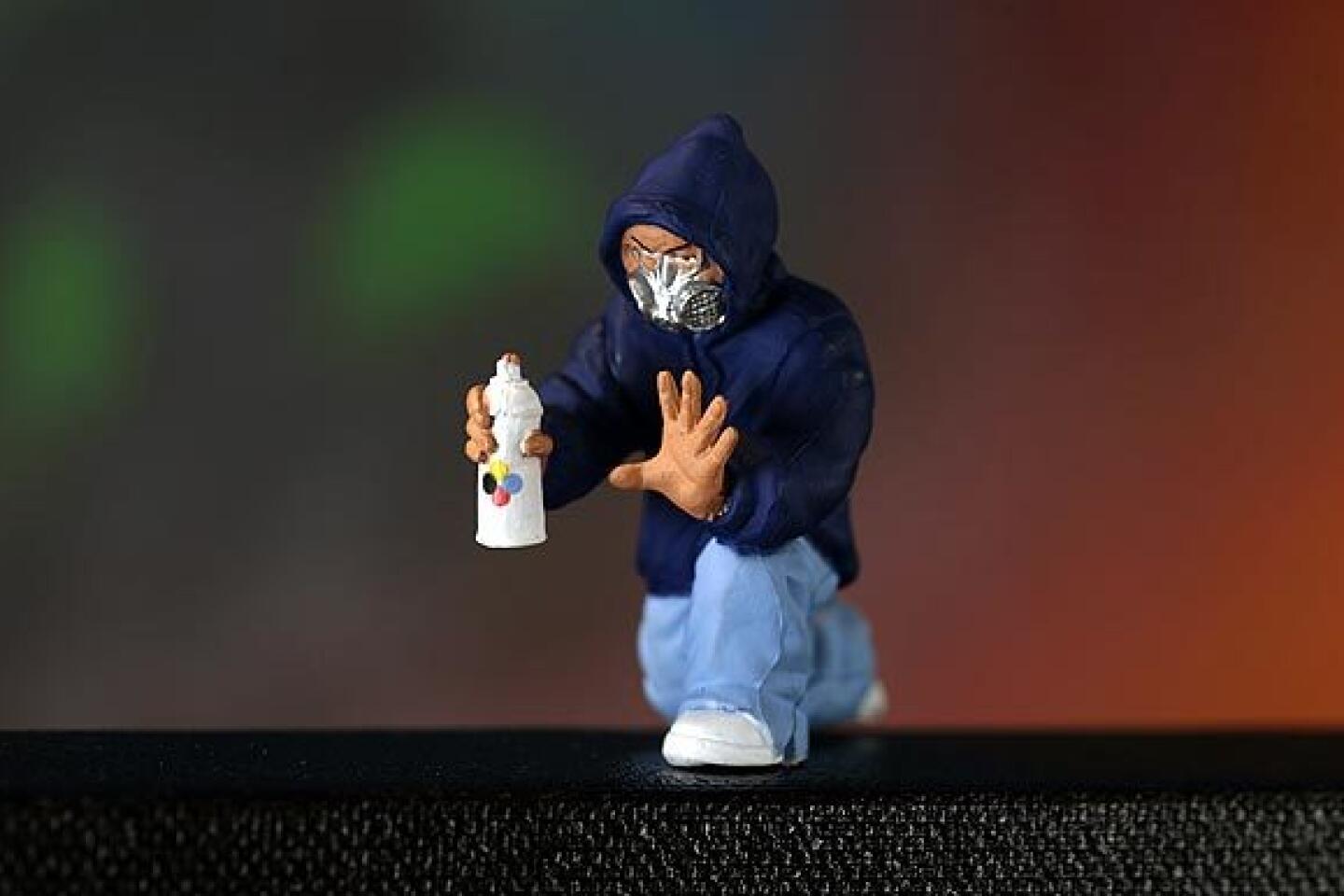

“Clever,” a graffiti artist, is concealed by a hooded sweat shirt, spray paint in hand. “Lucky” is rolling dice on a street corner, a wad of cash in his hand.

There are 42 in all, seven sets of six, with more to come. There are four dogs, one a lunging police K-9. There are three cops, all with their guns drawn. There are four women. The rest are men. They are all Latino, except for one white man, a vagrant, and two African Americans, both named Choco.

This, Izaguirre contends, is his valentine to South L.A.

He was born in the heart of Mexico, in rural San Luis Potosi. He was the second of seven siblings and the oldest son. His mother, Esperanza, named him Abel, because the biblical Abel, before he was killed by his brother, was a good and righteous boy.

His father had gone to the United States without them, and they rarely heard from him. Esperanza had to borrow money to feed her children. “One day,” Izaguirre said, “she just came home and said: ‘We’re leaving. We’re going to look for your dad.’ ” Coyotes sneaked them in near Tijuana, through a tunnel full of water up to his knees. The smugglers had no flashlight, just matches. When those ran out, they ran through the tunnel with their arms stretched into the darkness. He was 8 years old.

When they found Izaguirre’s father, he turned out to have a second, secret family in Los Angeles. But he agreed to help them find a place to live, and the family -- which later secured legal residency status -- moved into a one-bedroom apartment on West 92nd Street. It was the birthplace, in a sense, of the Locsters.

Izaguirre started working at 10, selling sweet bread and tortillas door to door for a bakery. Still, they celebrated no birthdays or Christmas. “We had nothing,” he said -- nothing but the streets, which began to pick off the Izaguirre boys, one by one.

One brother was arrested on drug and weapons charges, which brought a 10-year prison term. Another is serving 15 years to life for shooting a high school classmate. He’d been shot at the night before by members of a rival gang. Knowing he was going to get jumped, he tried to ditch school the next day; his mother made him go.

“So he got one of the guys before they could get him,” Izaguirre said.

Izaguirre offers no apologies for his brothers’ decisions.

“My brothers are the greatest people in the world,” he said. “You put them in a corner, and there’s no other way. They fight back. In South-Central you don’t call the police. We protect our own.”

Luis, the youngest of the five boys, was killed in 1995, shot nine times after a dispute at a market, where he had gone to buy chips and candy. He was 15.

Izaguirre chalks up his survival to a combination of luck, guts and guile.

“But the truth is, I don’t know why he’s different,” his mother, now 65, said in Spanish. “We live among the gangs here. Some boys join. Some boys don’t.”

Art was his refuge. His medium of choice was spray paint. He would ride the bus to lots wedged behind warehouses or railroad tracks. These “yards” were known only to a small cadre of accomplished graffiti artists, not the kind who tag on the run, but the kind who paint large and colorful -- though no less illegal -- murals.

“We didn’t get hassled by the cops. It was our own little world,” Izaguirre said. “I really thought I was going to grow old doing graffiti.”

But after he dropped out of high school, Izaguirre discovered that it did not pay the bills.

Izaguirre started designing T-shirts, then painting designs on cars. He designed a line of skate shoes and sold 200,000 pairs. He designed the logo for “Monster Garage,” the Discovery Channel show. About 10 years ago he partnered with the owner of a hobby company and began making toys, including Locsters. More than 3 million figurines have been sold in markets, toy stores and record shops.

Depictions of inner-city America, many of them bleak, have spread through pop culture in recent years.

Perhaps the best-known urban figurines are Homies, which have sold in the tens of millions, despite criticism from members of the Los Angeles Police Department, among others.

Izaguirre can’t figure out why anyone would make a fuss over the Locsters.

Perhaps that’s why Izaguirre has received only a handful of complaints, though Locsters are -- he says proudly -- the most graphic urban figurines to date.

Many of his characters, he said, are based on real people from South L.A., like “Tattoo Tony,” who comes with an ink gun in hand.

“South-Central is in my veins,” Izaguirre said, and in that sense, his Locsters are a mere tribute. Even the most intimidating Locsters, he said, are just trying to survive another day, just “posing,” he said, so they’ll be left alone.

“Everybody who grows up in the ghetto, they’re all good people,” he said. “Nobody is born a gangster.”

In 2000, Izaguirre left South L.A. and bought a four-bedroom, 2,500-square-foot house in Chino Hills. The boy from San Luis Potosi would barely recognize this life.

He rented space in a nondescript office park in the southwest corner of San Bernardino County, where the streets are lined with baby magnolia trees. He keeps a close eye on China’s labor movement, which has bumped up import costs.

“I have an IRA,” he said, still surprised.

Izaguirre is a father of four -- three daughters and a 13-year-old son, whom he takes deep-sea fishing in Cancun. His fans know him as O.G. Abel; “O.G.” is common street vernacular for “Original Gangster,” but his kids say it means “Old Guy.” He recently added a pool to the house, 6 1/2 feet at the deep end.

“In Mexico, we used to swim in the mud when it rained hard,” he said. “I’m just living the American dream.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.