Get Lit Players bring poetry’s emotions to other L.A. teenagers

- Share via

Scott Gold — For as long as he can remember, Dario Serrano’s life was all screeching tires and echoing gunshots, babies’ cries and barking dogs, a symphony, as he puts it, of “hood rats and gangsters,” of “vatos vatos and payasos” -- dudes and numskulls, loosely translated.

By high school, he’d pretty much given up on himself. He bounced around between three schools. He started selling pot, though he always seemed to smoke more than he sold. His GPA fell to 0.67, which is about as bad as you can get and still be showing up.

Literature, it is fair to say, was not resonating. “I mean, ‘The Great Gatsby’?” he says incredulously, and when he puts it like that, Lincoln Heights does feel pretty far from Long Island.

When a friend suggested that poetry might be his thing, Serrano scoffed. Grudgingly, he started tagging along to a poetry club, and one day last year he took his lunch break in a classroom where a teen troupe called Get Lit was holding auditions.

Get Lit’s artistic director, an African American artist named Azure Antoinette, performed an original composition called “Box,” a denunciation of anyone who would define her by the color of her skin, who would lump together, thoughtlessly, faces of color:

“The general population has come to a consensus that we don’t have a prayer,” she said, her voice filling the room. “All we have is prayer. . . . We are not victims.”

This, Serrano thought, was something he could get behind.

Today the nonprofit Get Lit Players are barnstorming Los Angeles, kids performing for kids, thousands of them over the course of a dozen school performances this winter and spring.

Some of their readings are of the classic variety -- Ezra Pound; Langston Hughes; “The Boy Died in My Alley” by the great Gwendolyn Brooks, written in the voice of a girl who confesses that she heard the gunshot but didn’t think much of it because she’d also heard “the thousand shots before.”

But much of their material consists of in-your-face original compositions -- about teenage mothers and mixed-race children, about gang violence and immigrant pride -- that are performed in English, Spanish, Portuguese and Bengali, like a soundtrack to a modern, messy L.A.

Serrano, now 18, has become a troupe leader. Poetry, he says, saved his life. He graduated last year from Marshall High School, earning straight A’s in the homestretch, he said, and now attends East Los Angeles College, where he is considering a career in education.

One of his compositions, “Home Is,” is an anchor of the Get Lit shows. Like many poets before him, Serrano has discovered that unvarnished autobiography often makes for the strongest material:

You can say it to my face; I ain’t afraid to admit

I was other stereotypes: A joker, a drug broker, a known toker, a first day of school loner

A drug abuser, a street cruiser

But I guess you can say

I’m a geek, incognito

It is a rainy afternoon in West Hollywood, and Diane Luby Lane is insisting that she is not a crier, though this is the third time she has cried before finishing a bowl of soup. They are not tears of sadness, nor joy, but rather a passion for the written word that feels disarming in a busy, digital world.

“Listen to this,” Lane says, and from her purse, she produces a copy of Walt Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass” that has very nearly been loved to death. She reads from Whitman’s “Song of Myself”: “I will not have a single person slighted or left away.”

“He’s saying: ‘I’m for you,’ ” Lane says; literature, in other words, is for everyone.

Lane, 40, Get Lit’s founder and executive director, did not always believe that.

She does not equate the troubles of her youth with the difficult lives of many troupe members; her childhood in suburban New Jersey, she says, was merely unimaginative.

She was a middling student and did not find literature until after she dropped out of college. It was the late 1980s, and she was modeling overseas. The other models, from Russia, Germany and France, “were not brain surgeons,” she said, yet they were versed in Tolstoy, in Goethe. Lane decided that she should be, too.

The other thing she keeps in her purse is a journal titled “Books I’ve Read,” and they’re all there, hundreds of them, including “Shogun” and “Animal Farm”; seven Carlos Castanedas in a row; plays by Neil Simon.

In 2005, she launched a well-received one-woman show about books and the impact they had on her life, which begat similarly themed school workshops and then Get Lit. Lane makes her living as a successful commercial actor, but makes her life in poetry.

“This is so cheap and so accessible, something we can get into the hands of our kids,” Lane says, holding up her Whitman. “They will find what they are looking for. A lot of children are just broken. But they can be saved.”

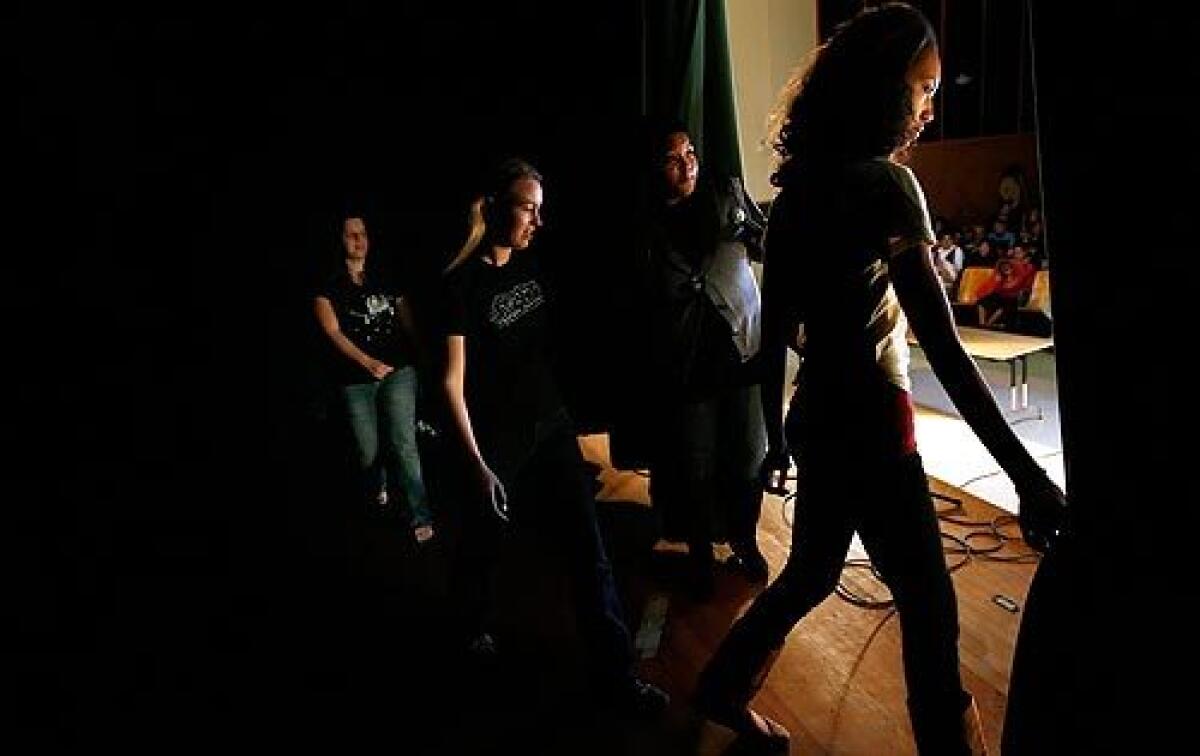

On Wednesday, the troupe huddled behind a thick theater curtain in the auditorium of Dorsey High School. Its shows are designed to drum up interest not only in poetry and literacy, but also in the auditions Get Lit will hold in coming weeks. This one looked like it might be a tough show, and a tough sell.

No one seemed to know how to operate the auditorium’s lights, or the thermostat, for that matter, turning the building into a dank, dim grotto. The 200 students filing in, meanwhile, looked uninterested at best. Many had hooded sweat shirts pulled over their faces; a few wore sunglasses in the dark room. When Lane and Antoinette performed an opening segment, intertwining poetry with dizzying statistics about illiteracy and education, there were audible yawns.

Backstage, Lane gathered her flock. “Remember,” she told them, “you are poets. They have never seen literature the way you do it.” She was right.

Ryan Jafar, a 17-year-old from the Los Angeles Center for Enriched Studies, took the stage first.

He blinked into the restless crowd, then said quietly: “This is for everyone who’s ever felt weird or different.”

Then he launched into an original composition, “Space Traveler.” Before long, he was on fire, ranting against pop culture “garbage” and rampant commercialism.

By the time he reached the climax of his piece -- “Cars? Clothes? Hos? No! No! No!” -- the audience was roaring its approval.

Over the next hour, the performers deftly wove together well-known poetry and hip-hop-styled “slam” poetry. Serrano performed “Alone” by Edgar Allan Poe, but not before pointing out that he’d often felt alone himself, back when he was flunking out of high school:

“From childhood’s hour I have not been as others were.”

Jafar compared a line from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “The Children’s Hour” to a line from Talib Kweli in which the hip-hop artist dotes on his son. “It’s the exact same thing,” Jafar told the students. “Just in different language.”

By the time it was over, 12 students had joined the troupe onstage to sample poetry and pledge to audition.

Antoinette, the artistic director, closed the show with a performance of “Box,” the poem that got Serrano hooked two years ago:

Don’t put me in a box

If you must, put me in a box of writers, poets, artistic dreamers, patriots for world peace. . . .

Put me in a box with no walls, no top, no bottom . . . where I will flourish, where I can turn the Earth on its ear.

Serrano, his work done for the day, listened from the darkness backstage, his eyes closed, his body swaying to the rhythm of the words.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.