Young advocate seeks pope’s aid on immigration

- Share via

A 10-year-old student from Noble Avenue Elementary School in North Hills visited the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels last week on a diplomatic mission.

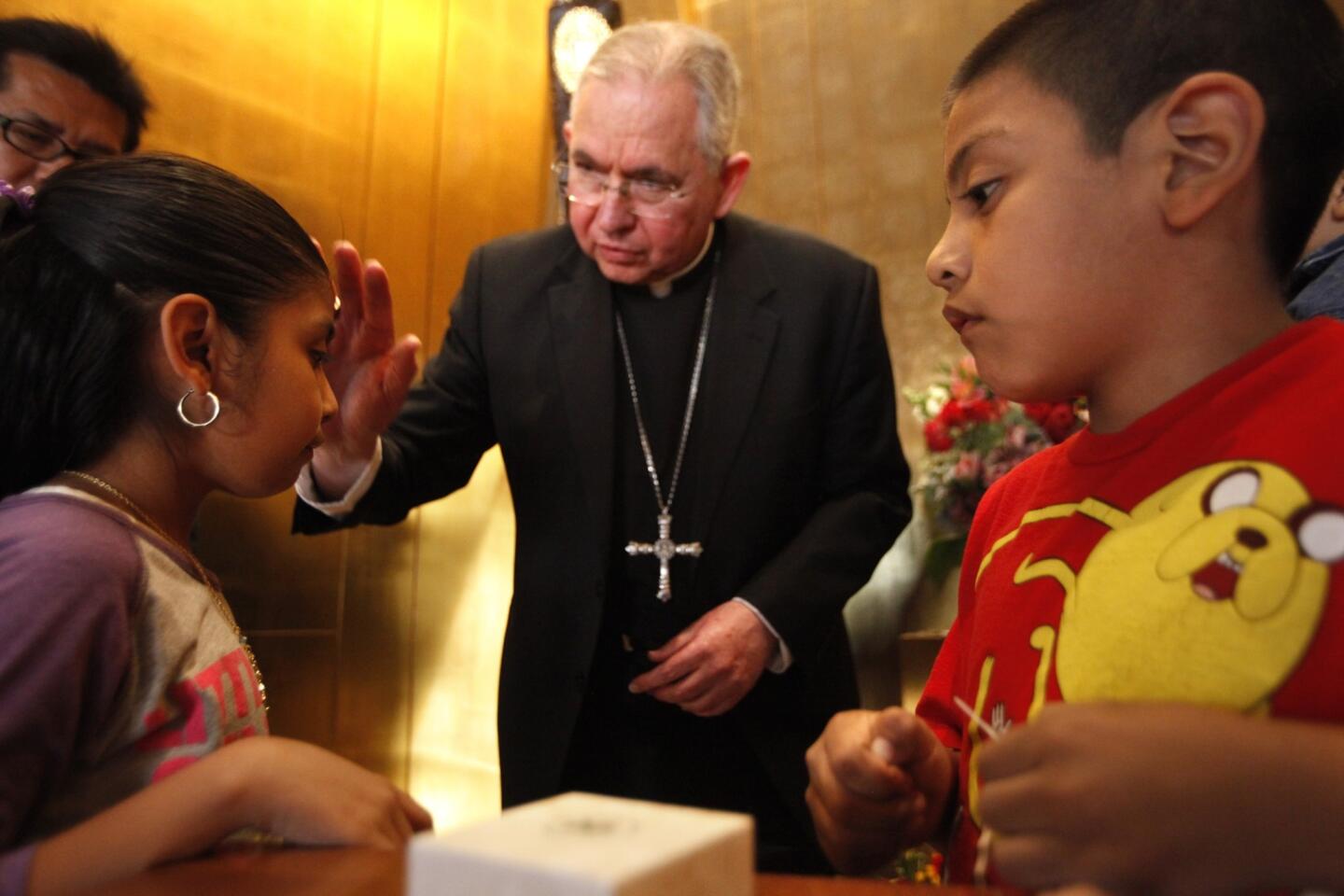

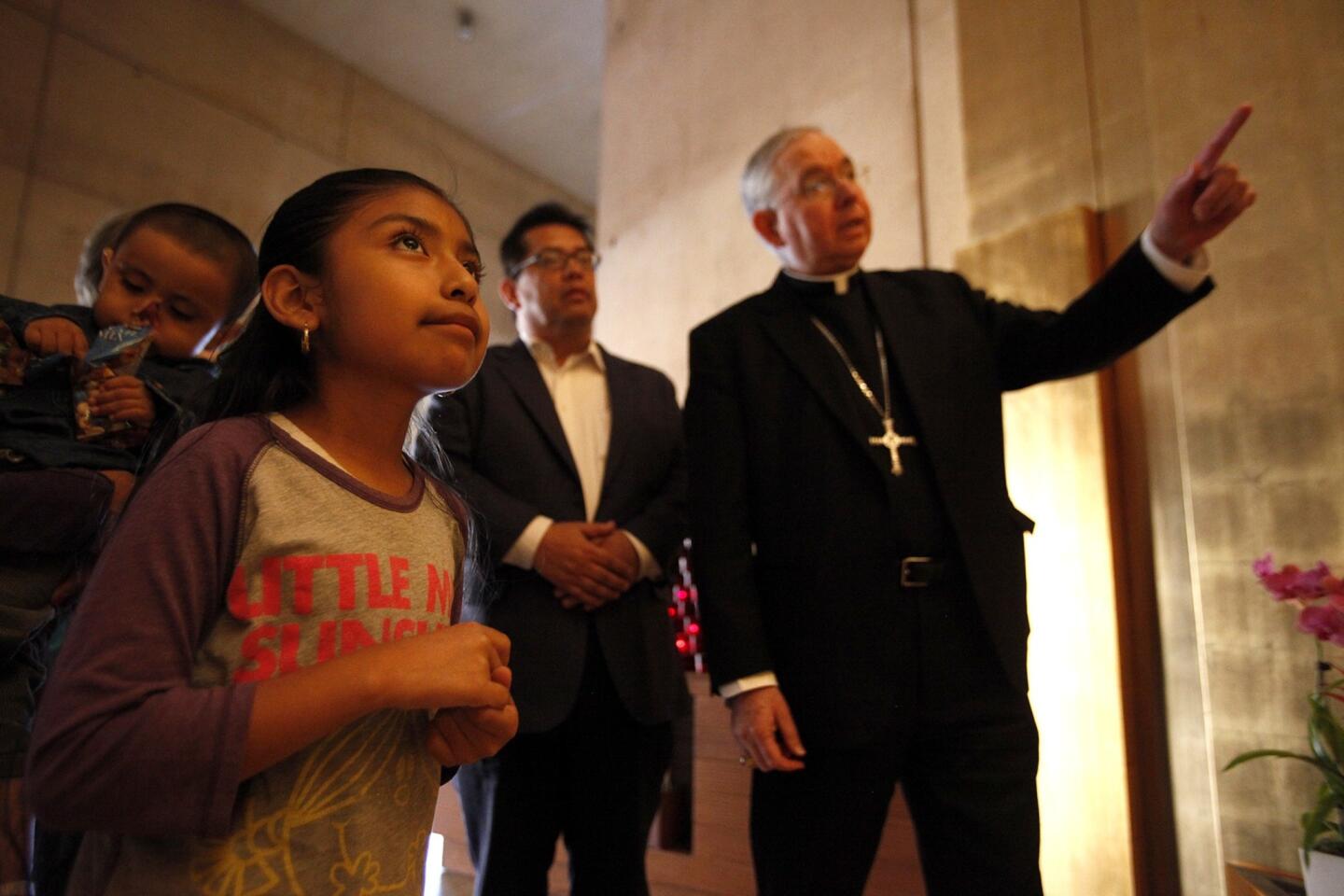

Jersey Vargas, a fourth-grader, was about to leave for Rome and a possible visit with Pope Francis, but first she wanted to ask Archbishop Jose H. Gomez for his blessing and his help. Jersey said she hoped the archbishop will “help my Dad out, so he can be with me and my family, and we won’t be separated ever again.”

Her father has been in custody since September, Jersey told me. She said he “was caught driving without a license, and because he wasn’t born in the United States, that also didn’t help him out…. So now he’s in another state, I think in Indiana, and he’s with immigration and they’re going to deport him.” Jersey’s father, Mario, was working a construction job out of state at the time of his arrest. Since then, his wife, Lola, has been baby-sitting, selling tamales and cleaning houses to support the family.

Archbishop Gomez, a naturalized U.S. citizen who was born in Mexico, has heard hundreds of similar stories. But he told me that he hadn’t met anyone this poised and articulate at such a young age.

“I came here,” said Jersey, who was with her mother and two brothers, “so everyone could hear me and not ignore me, because I want them to feel the pain and how I’m feeling very sad because now I don’t have my dad with me. And when I see other girls with their parents, I wish I were them.”

When Jersey’s mother sought help after her 43-year-old husband’s arrest, the Full Rights for Immigrants Coalition stepped in. Once they got to know Jersey and her family, the group’s coordinator, Juan Jose Gutierrez, realized that they might help put a human face on how deportations split families.

The group arranged the meeting with Gomez and also helped set up the Rome trip, where Jersey and other citizen children of people living in the U.S. illegally hope to persuade the pope to take up their cause with President Obama when he visits the Vatican on Thursday. The president said recently that he wanted to avoid splitting families in which someone living in the U.S. illegally is a longtime resident without a record of serious crime.

I asked Jersey if she had been to Rome before.

“I haven’t even been to Disneyland,” she said.

And if she meets the pope, what will she say?

“I’m going to introduce myself and where I’m from, and say I’m representing millions of children who today are in my situation … and I think it’s unfair that people are separating families because right now is a time when kids really need their parents.”

Her communication skills are no surprise to Noble Elementary Principal Cara Schneider, who said teacher Laura Hanley spotted Jersey’s gift in first grade and helped her become a voracious reader and young scholar.

“Every time I have an honors assembly, she’s one of the students being honored,” Schneider said. “I can’t wait until I can vote for her for president of the United States.”

That may be a ways off, and the same can be said for immigration reform. I told Archbishop Gomez that I get hammered when I write about the subject, and he gave a knowing nod.

“Every time I say something I get negative responses from people,” Gomez said. He receives “emails and letters telling me that I shouldn’t be talking about it, that it’s against the law.”

Indeed it is, and both Jersey’s parents did come here illegally. Aside from social and law enforcement costs, critics understandably complain that to look the other way on people living in the U.S. illegally is to undermine the rule of law.

“We bishops are not in favor of illegal immigration,” Gomez said. “We are in favor of legal immigration. But we have a reality we need to find a solution to — people are already here.”

They are here in part, Gomez said, out of economic desperation and because of a history of mixed signals from the U.S., which has looked the other way when cheap labor was needed. He said those here illegally should be held accountable with fines and maybe a community service requirement. And they should have to educate themselves about the country’s laws and government. But to him, deportation is too severe a penalty in most cases.

In a speech in January, Gomez said he has heard the argument that those who are in the U.S. illegally should be kicked out and wait in line to come back legally. That demands “an almost inhuman choice,” he said in the speech, noting that it could take 10 years or longer for people to see loved ones again.

“We need to put ourselves in their position,” Gomez said in the speech. “Would we follow a law if it means maybe never seeing our families again? These are hard questions we have to ask ourselves as citizens and as a nation. That’s why I believe immigration reform is a question about our national soul.”

Alex Galvez, a local immigration lawyer, said a judge agreed Thursday to release Jersey’s father pending a later review of his case if the family can post a $5,000 bond. As part of his argument for not deporting Vargas, Galvez argued that he was his family’s breadwinner, that he had been in the U.S. since the age of 16, and that his children include a 10-year-old junior scholar.

Jersey, lifted by the news of her father’s possible release, left Friday evening for Rome.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.