Mecca, by way of Costa Mesa

- Share via

The students stared at the overhead screen and read the words in unison:

Labbaik. Allah humma labbaik.

The Southern California Muslims repeated those words -- “Here I am, Lord. I am here to serve you” -- as they donned pilgrims’ robes last week in the Saudi Arabian city of Medina, a key step on their pilgrimage to Mecca.

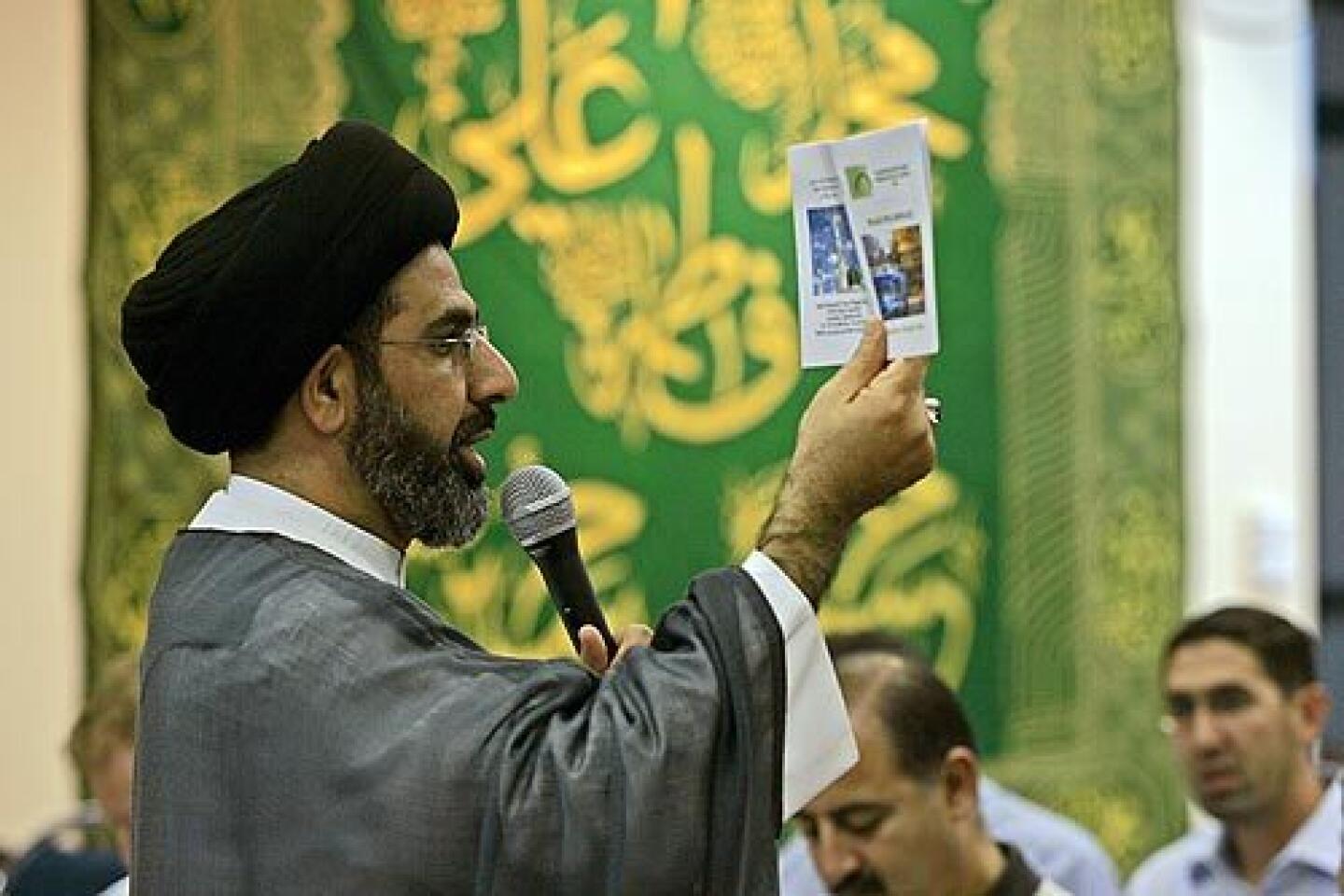

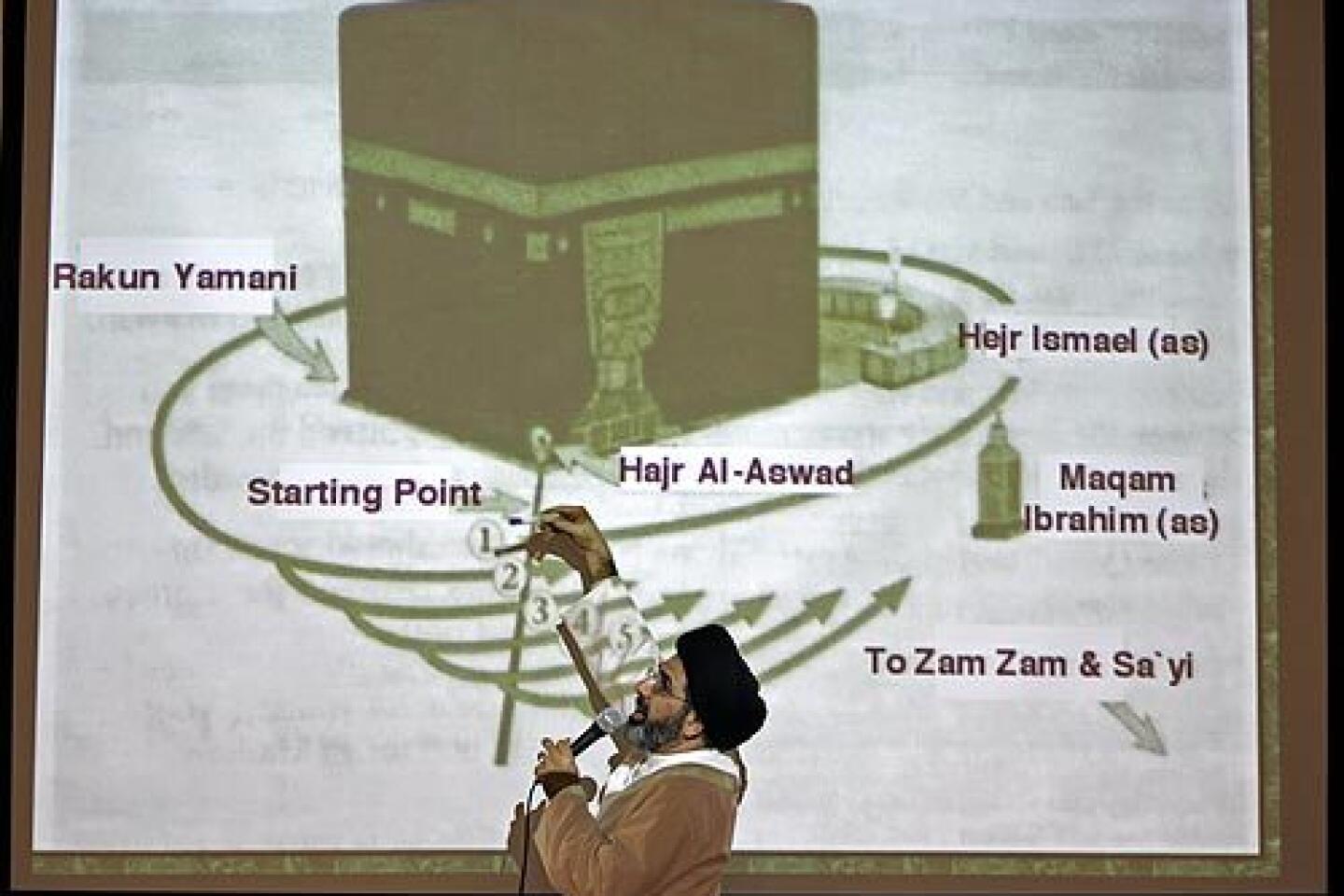

On the night they watched the overhead projector, the pilgrims-to-be had assembled in a more prosaic spot, a mosque tucked in a nondescript Costa Mesa office park in the shadow of John Wayne Airport. They were gathered with their teacher, Imam Moustafa Al-Qazwini, to learn the intricate and ancient rituals surrounding the hajj, the pilgrimage that is considered the spiritual pinnacle of a devout Muslim’s life.

“You are telling the Lord: I have traveled all this distance, left my home and my business,” Qazwini said. “Here I am, Lord. I’m available for you. I am your servant.”

Equal parts spiritual odyssey and physical endurance test, the hajj often demands years of planning, hoping and saving -- all culminating in an intense, sometimes dangerously chaotic five-day whirlwind.

This year, the hajj begins today. To help prepare about 25 of his students, Qazwini, 46, head of the Islamic Educational Center of Orange County, had organized a series of “hajj lessons” starting in late November. In them, he guided his charges through discussions that ranged from the spiritual (ask forgiveness of people you have offended) to the practical (the best places in Anaheim to buy hajj robes).

His tone ranged from high school teacher to stand-up comic. Pilgrims are prohibited from wearing cologne, perfume or beauty products, he taught, explaining: “You have to be as natural as God created you.”

“But you do have to take showers, please!” he added, drawing a laugh from his students.

Another hajj stricture: No physical intimacy -- not even kissing -- is permitted during the several-day span when the pilgrims are in the state of holiness and purity known as ihram. But the no-sex rule would not apply to their entire three-week stay in Saudi Arabia, he added.

“So don’t worry,” he said, grinning.

For the pilgrims in Qazwini’s group, the mix of the sacred and the practical filled the weeks leading up to their departure.

“You’re spending all this time getting ready and running around and you almost don’t have time to think about the spiritual experience,” said Ellen Hajjali, who is making the pilgrimage with her husband, Raef.

“It won’t hit us until we’re actually there,” said Raef Hajjali, 51, a construction manager.

“No. It’ll hit me on the plane when I won’t have any more lesson plans to do,” said Ellen Hajjali, 46, a teacher at the New Horizon School in Pasadena.

At home in Altadena the week before their departure, the Hajjalis showed off their ihram clothes -- the simple white robes that all pilgrims wear -- and detailed their daunting pre-trip to-do list: Raef Hajjali had been advised by hajj veterans that, amid the crush of pilgrims, it’s almost impossible to find your sandals after taking them off at the mosque door, so the couple were scrambling to buy multiple pairs.

Ellen Hajjali fretted about whether to take extra eyeglasses in case hers were crushed in the crowds. She also worried about what she called “the bathroom situation” on the desert plain of Muzdalifa, where an estimated 3 million pilgrims will hold a prayer vigil Tuesday and sleep on the ground under the stars.

Qazwini warned during his hajj lessons that the public bathroom lines in Muzdalifa are “longer than Disneyland’s.”

“It’ll be like camping -- just with 3 million other people,” Ellen Hajjali said, trying to put a brave face on the situation.

Ellen and Raef Hajjali also were finalizing their wills, a standard pre-hajj step and a reminder that some pilgrims don’t come back from Saudi Arabia alive.

In 1997, fire swept through a series of pilgrim tents, killing more than 300. In 2004, 251 people died in a stampede in an enclosed area where pilgrims throw pebbles at a series of black stone pillars, a ritual known as “stoning the devil.”

The site of the stoning ritual has seen numerous deadly stampedes, and the Saudi government has extensively remodeled the area to make it more spacious and safer.

Amid the mundane preparations, the spiritual power of the journey sneaked up on Ellen Hajjali, a Catholic-born convert to Islam. A couple of times, while telling friends and relatives that she was going on the hajj, she suddenly found tears rolling down her cheeks.

She had pressed her husband for years to make the journey. “But there wasn’t enough time with our schedules. Life in America is like that,” said Raef Hajjali, a Lebanese immigrant who met his wife almost 30 years ago in a French class at Glendale Community College.

“Finally this year, she said, ‘If we’re not going together, I’m going without you,’ ” he said.

She had realized that this hajj would be the last one in years to coincide with school vacations. Because Islamic festivals are set on a lunar calendar, the hajj moves up about 10 days each year in relation to the Western calendar.

If the couple did not go this December, they would have to wait more than a decade for it to align with August vacation time. And even that would be of little help -- the Hajjali family are Shiites, as are most of Qazwini’s group, and Shiite custom forbids shielding one’s face from the heavens in any way during the hajj. The thought of a summertime pilgrimage through the desert without even sunscreen horrified Ellen Hajjali, who inherited the pale skin of her Irish ancestors.

Another student-pilgrim, Mohammad Al Mithani, 22, has been trying to go on the hajj with his parents for three years. Previous plans fell apart, but this year he received his Saudi visa -- normally a several-month ordeal -- in a week. An understanding boss at Southern California Edison, where he works in the information technology department, allowed him to go even though Mithani had used up his vacation time.

Like many pilgrims, Mithani views the hajj as a chance to wipe away his sins and start anew, reborn and rededicated to his religion.

“Everyone wants to get better -- to be a more moral person, a more ethical person,” he said after a recent hajj class. “I want to become someone who has piety and wisdom.”

A few weeks after that conversation, Mithani, the Hajjalis and other pilgrims arrived in separate waves in Medina earlier this month, exhausted by 48 hours of travel but energized by the knowledge that one of the holiest sites in Islam was 100 yards from their hotel.

Ellen Hajjali, already freckled after one day in the Saudi sun, recounted a difficult journey that included several hours sitting on a bus while Saudi authorities searched for their paperwork. Still, they had made it.

“You hear the names of these mosques and holy sites, but to actually be here -- it’s just amazing,” she said.

Medina is home to the tomb of the prophet Muhammad, his former house and the pulpit from which he preached to the first community of Muslims about 1,400 years ago. All are now embedded within the Mosque of the Prophet, a vast marble monument with towering minarets, dozens of glittering domes and a two-story parking garage underneath.

Visitors to Medina line up in droves to view the large wooden box that conceals Muhammad’s grave site, each saying as they pass: “Peace be upon you, O Prophet of God.”

In addition to the historic religious shrine, Medina is home to a Starbucks, a Kentucky Fried Chicken and dozens of modern hotels catering to religious tourists. The American pilgrims found the contrast disconcerting.

“I thought I would be walking in the footsteps of the prophet, and at times I certainly did feel that,” Ellen Hajjali said. “But being in the middle of all this modern luxury did take a little away from that.”

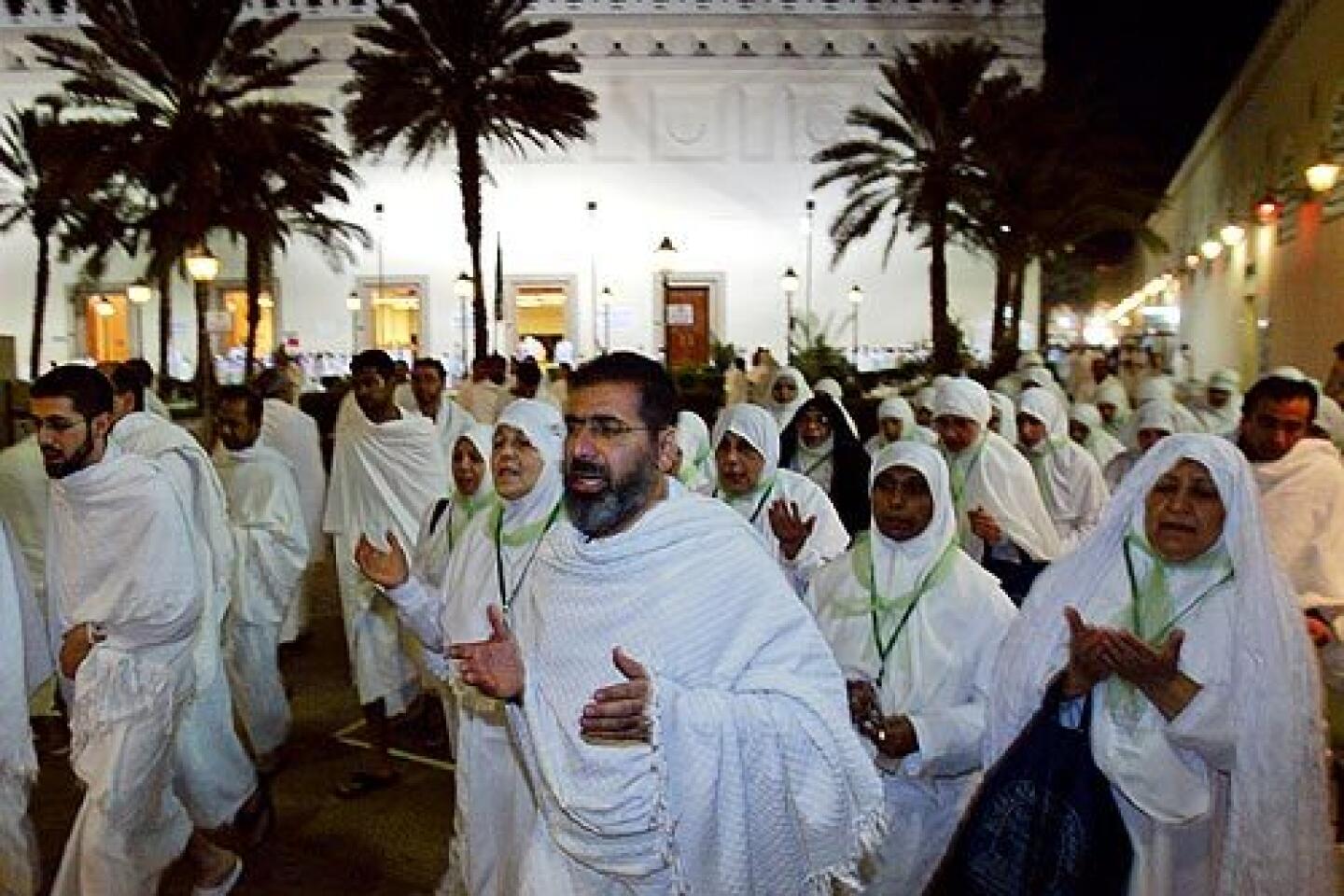

Then it was time to formally enter the state of ihram. The pilgrims took ritual showers Dec. 9, speaking directly to God as the water ran over them. They declared their intention to perform the pilgrimage; they asked God to accept their offering.

Then they donned their simple ihram clothes -- a constant, deliberate reminder that all pilgrims, rich and poor, are equal in the eyes of God. Thus dressed, the Americans blended in with the gathering throngs of pilgrims from scores of nations.

Under Qazwini’s direction, they boarded buses to Mecca, chanting the prayer they had learned weeks before:

Labbaik. Allah humma labbaik.

First in a series of occasional articles about Southern California pilgrims on the hajj in Saudi Arabia.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.