A cold case is revisited

Investigators thought they had a solid suspect in the 1988 slaying of Aleta Browne. Years later, another detective pulls the case out of the cold.

- Share via

The Investigation

The following records are part of the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Dept.'s investigative file on the 1988 killing of Aleta Browne.

Aleta Browne fell hard for Fred Nixon.

She was both a sister and wife of Los Angeles cops, and worked as a clerk for Police Chief Daryl Gates. Nixon was one of the LAPD's rising stars, on his way to taking over a coveted position as the chief's official spokesman.

Their affair began on a spring day in 1985 when they checked into a Holiday Inn. Browne left her husband a few weeks later.

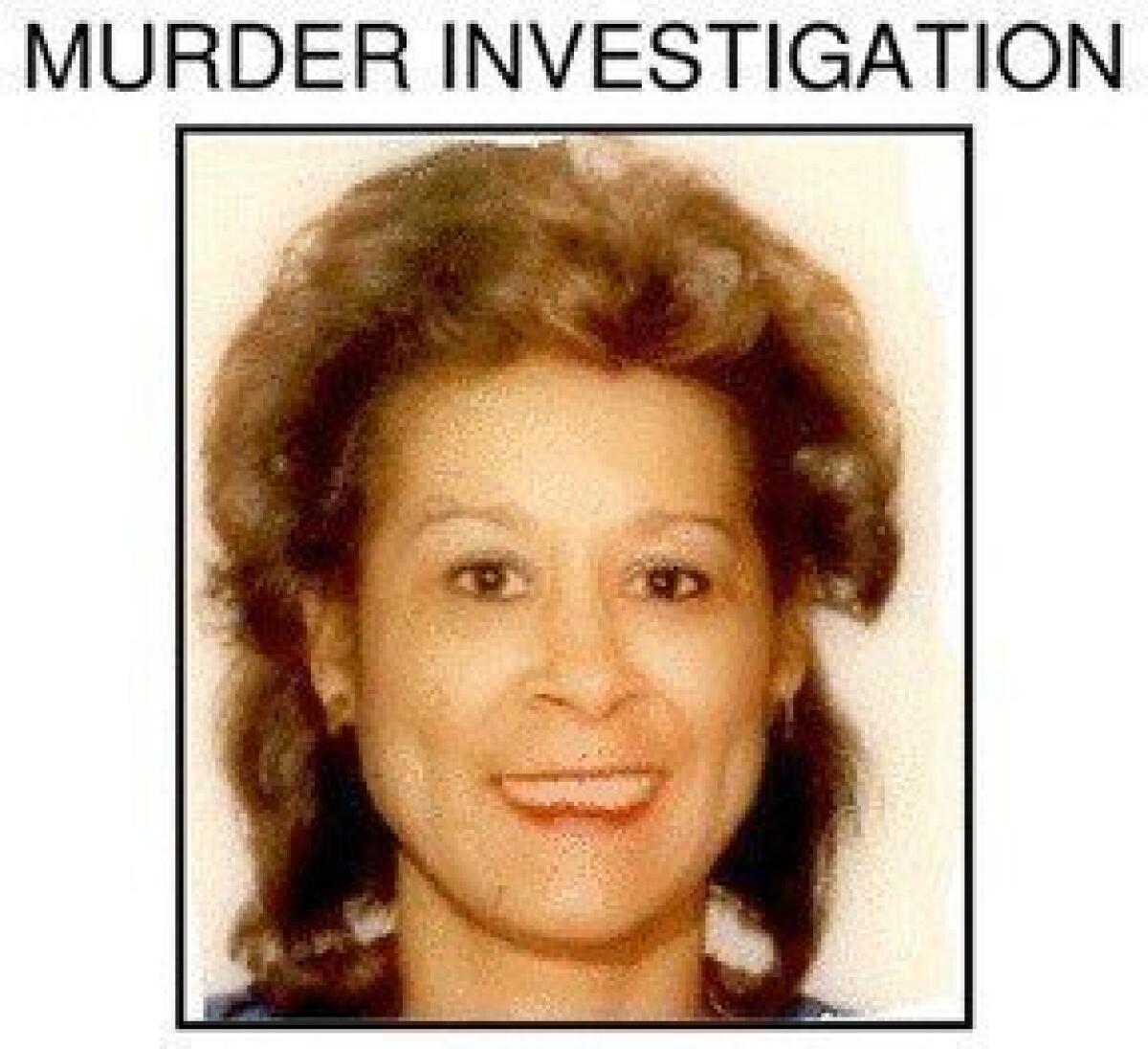

A Feb. 2010 flier seeking information

Fred Nixon

For three years they met regularly, often at her house during the day. At night, he'd go home to his wife in Pasadena.

Then, one morning, Browne was found beaten and strangled on her bathroom floor.

The crime scene was outside the Los Angeles city limits, so it fell to the L.A. County sheriff's department to investigate. Detectives looked at Nixon as a suspect, but they gave up on the case without filing charges. Nixon, who over the years has maintained his innocence, worked another decade before retiring and moving to Oregon.

Twenty-two years after the killing, in 2010, Robert Taylor, a cold case investigator in the sheriff's office, reopened the file.

This story is based on the Sheriff's Department's investigative file, obtained by The Times. It includes Browne's letters and personal journal, transcripts and audio recordings of interviews conducted by detectives, wiretap information, the autopsy results, investigators' field notes and internal department correspondence.

"Call the police! I can't get her up!" Nixon shouted. "My girlfriend is dead!"

He was pounding on the front door of a house next to Browne's home in South L.A. It was shortly after 7 in the morning, March 26, 1988.

Det. Patrick Morgan and Sgt. Dirk Edmundson, sheriff's homicide investigators, found Browne face-down on the bathroom floor, wearing underwear and an unbuttoned red nightshirt.

Her legs jutted into the hall. Her left eye was swollen nearly shut. Narrow, dark purple bruises encircled her neck.

The detectives found no sign of forced entry. On the kitchen counter was a bottle of Canadian Club whiskey, a club soda and a can of Hawaiian Punch with a straw in it.

There had been struggle. A plant and large brass stand in the living room had been knocked over. Nearby, the rug was stained with blood. The bedroom had been ransacked, clothes and papers dumped onto the floor and bed.

Browne's 8-year-old Ford Mustang was gone, but nothing else of value had been taken. The only things that seemed to be missing were some of the final pages from Browne's diary.

Sgt. Dirk Edmunson's crime scene notes

Det. Patrick Morgan's notes on the victim

The coroner concluded that Browne's killer had strangled her first with a cord or something similar, and then applied a crushing chokehold.

The autopsy revealed something else: Browne was nearly seven months pregnant. Two separate homicide files were opened — one for Browne and one for her unborn girl.

Topping the detectives' list of potential suspects was Browne's ex-husband, the LAPD cop. But he insisted he hadn't spoken to her for months. After he passed a lie detector test, Morgan and Edmundson eliminated him as a suspect.

The detectives turned their attention to Nixon.

From her journal, and interviews with her friends and Nixon, the investigators learned that Browne and Nixon had had a tumultuous relationship. More than once, Browne broke things off, only to reconcile.

Excerpts from Browne's journal

"I've been living in a shell for almost a year and a half now. It's like I'm only alive the short time we're together once a week," Browne had written in 1986. "I'm not made to live like this. I can't go on like this … I need you so much — I really am going crazy. I LOVE YOU."

In her journal and letters, she recounted her pleas that Nixon leave his wife — and his excuses for not doing so. He claimed that his wife had attempted suicide when she discovered his plans to seek a divorce. Another time, he said his wife knew things about his past and was threatening to report him to the department's internal affairs unit if he left her. (His wife later told detectives that neither was true.)

In her calendar, Browne noted days on which she made anonymous phone calls to Nixon's wife, once threatening, "Watch your back. You can't get away with what you're doing to Fred." In March 1987, she wrote Nixon's wife a letter detailing the affair and her feelings for Nixon, including personal details, such as his habit of shaving his armpits and the type of underwear he wore. Detectives found a copy of the letter among her possessions.

Detectives learned from Nixon's wife that her husband intercepted the letter before she could read it. When she demanded to know its contents, he admitted to having an affair but told her he had already ended it.

Three months before Browne died, on Christmas Eve 1987, she told Nixon she was pregnant. At 42 years old, he had adult children and told investigators he was initially unhappy with the idea of being a father again, but came to accept it. Browne wanted to have a baby and had been unable to conceive. Now, nearing 40, she wrote that she was determined to have a child.

In fact, she already had a name picked if it was a girl. Alicia Marie.

Nixon came clean with the investigators about the affair, saying he was with Browne the day before she was killed. He had decided on a whim to take the day off and surprise Browne at her house, he said. They went out for breakfast and returned to Browne's house, where Nixon said he poured himself some of the Canadian Club whiskey and the two had sex.

He said he returned to his home that afternoon to run errands with his wife. He and his wife ate Mexican takeout food and watched rented movies until he went to the bedroom to read and eventually fell asleep, he told investigators. His wife vouched for his alibi.

The next morning, Nixon said, he woke early and returned to Browne's. He told detectives he was surprised to find a key had been left in a side door and, assuming Browne had gone to the store, let himself in. He checked the refrigerator for something to eat and sat down in the living room to watch TV and wait. But he soon got a feeling that something wasn't right, and when he got up to look around the house he discovered Browne's body, he said.

Los Angeles Times interpretation of crime scene documents. Photos from the L.A. County Sheriff's Department file.

Javier Zarracina, Los Angeles Times

However, a man who lived across the street told investigators he was certain he had seen a late-model silver Mercedes matching the one Nixon owned parked in front of Browne's house around 7 p.m. —several hours after Nixon said he had left. The man's adult son told the investigators he saw the car as well.

A letter from Browne to Nixon's wife. Sherri Nixon-Joiner said she never read it.

The Mercedes was still outside around 1 a.m., the neighbor said. Two hours later, when the son returned from a party, he noticed it was gone.

Investigators spent weeks interviewing Nixon's acquaintances and searching his phone and bank records, and came up with no evidence tying him to the killing.

In late June, Nixon was called in for a follow-up interview. Edmundson and Morgan asked him to take a polygraph test. Such tests are inadmissible in court but are used by detectives as an investigative tool. "I'll have to think about the poly," he told them. "I don't believe in the poly."

Edmundson then read Nixon his Miranda rights and told him that he was their primary suspect. Browne's neighbors, the investigators said, were ready to testify that his car had been at Browne's house late on the night that she was killed. The neighbors, Nixon said, must be mistaken. He had been home with his wife all night.

Investigating another department's officer for murder was delicate. Before they interviewed Nixon the day of the killing, sheriff's officials had called Nixon's boss, LAPD Cmdr. William Booth, who came to the station to speak with Nixon. Gates later instructed a pair of police detectives to keep tabs on the sheriff's investigation. And Edmundson and Morgan kept their top brass updated via confidential memos.

Over the next few weeks, Nixon scheduled several meetings with the detectives, only to cancel. Three and a half months after Browne was killed, he met with the detectives and told them he wouldn't take the polygraph test.

"We're at the point now where you're the only game in town," Edmundson said, according to a transcript of the recorded conversation.

Memo to Sheriff Sherman Block on investigation

"An innocent man has nothing to hide," Morgan added.

"I agree," Nixon replied, "but I believe that an innocent man can have something to fear."

The interview ended. Soon after, the case went cold.

One of Robert Taylor's first stops, when he reopened the Browne case 22 years later, was a warehouse in Whittier.

Nixon's Miranda rights card

The Sheriff's Department stores evidence from thousands of cases in the sprawling facility. Armed with a list of the evidence collected during the investigation, Taylor had come to dig through the past. In particular, he was in search of the first item on the list: "Fingernail clippings and scrapings."

In an interview with The Times, Taylor said he thought it was possible that, as she struggled to free herself, Browne had collected skin cells from her killer's arm on the underside of her nails.

The skin would have been of little, if any, help to detectives in 1988, when DNA technology was in its infancy. But by 2010, the science had advanced dramatically. If there was skin beneath Browne's nails, Taylor might have the hard evidence he needed to make a case.

He began sorting through the boxes of evidence from Browne's case and quickly became frustrated when he realized evidence from another slaying had been mixed in. His frustration soon gave way to dismay. After going through everything, he had not come across the fingernail clippings. The storage facility's records gave the reason: They had been destroyed in 1998. The sheriff's supervisor who signed off on it didn't remember why.

Evidence log

Over the next few months, Taylor tracked down Browne's old neighbors and people who knew Nixon. But a prosecutor in the district attorney's office advised Taylor that, in a case such as this, he would need more than circumstantial evidence.

So Taylor set his sights on Nixon's alibi. His wife at the time of the killing, Sherri Nixon-Joiner, had told the original investigators that she saw Nixon in their bed when she went to sleep the night Browne died — and in the morning when she woke. It would have been impossible for Nixon to sneak out of the house without her knowing it, she said.

Nixon-Joiner also had agreed to take a polygraph exam. Days later, however, she told the detectives she had changed her mind.

"Deal with Fred … make Fred take a polygraph," she told them.

The couple divorced after the slaying, and now Taylor thought Nixon-Joiner might have a different story to tell.

Taylor got a warrant to detain Nixon-Joiner for the purposes of fingerprinting her and taking a DNA sample. When sheriff's deputies brought her to the station near her Long Beach home, they led her into a room where Taylor and another investigator were waiting.

Taylor told Nixon-Joiner that he was re-investigating Browne's death, according to a recording of the interview.

He pressed Nixon-Joiner about the killing. They talked for more than three hours. She denied having anything to do with the slaying, but said that her marriage to Nixon had deteriorated by then. She had told the original detectives, in fact, that her husband had told her a week before the killing that he planned to leave her.

The two slept in different rooms, and on the night in question, she told Taylor, Nixon had gone to their bedroom while she remained in the living room and slept on the couch.

The detective circled back to that detail as the conversation wound down.

"Did you cover up for Fred?" he asked.

Nixon-Joiner paused.

"Well, I'm gonna tell you," she said. "Only to the point where I can say he could've gotten out...Could he have gotten out? Absolutely."

"Without you knowing it?" Taylor asked.

"Yeah."

"And he could have been gone …?"

"Several hours," she said.

Nixon-Joiner had cast doubt on the alibi. But Taylor still couldn't put Nixon at the scene of the killing.

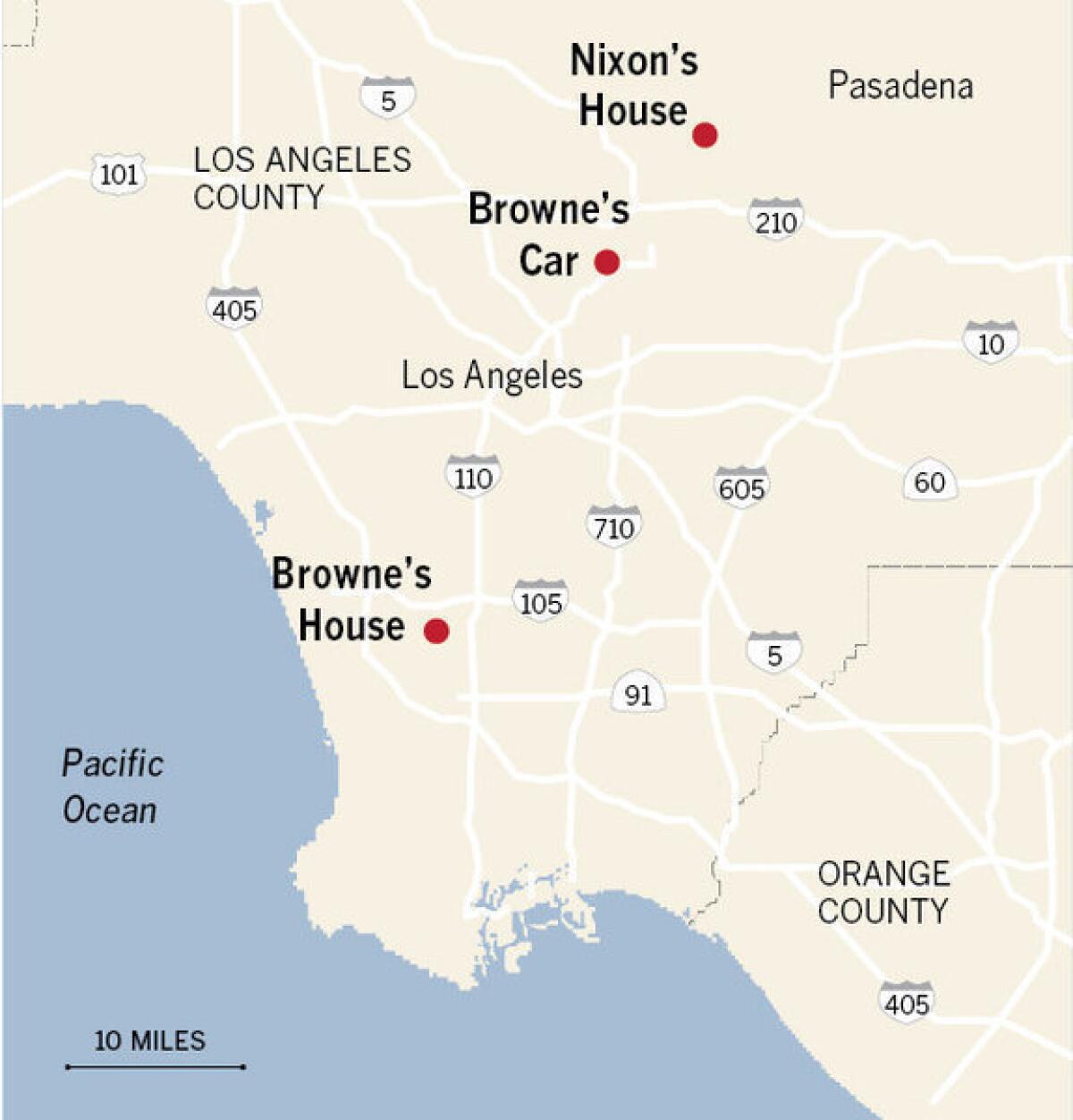

A few weeks after Browne's death, her Ford Mustang had been found with the keys in it at a gas station not far from Nixon's house. Taylor viewed the Mustang as an important, unexplained piece of the puzzle. If Nixon was involved, how could he have driven both his Mercedes and Browne's Mustang away from the house?

Nixon-Joiner grew quiet when Taylor asked if she knew the location of the gas station. Had she received a call from her husband the weekend of the slaying, asking to be picked up anywhere?

"I think I did," Nixon-Joiner said. But she couldn't remember where.

"This is so very critical," Taylor urged. "If you received …"

She cut him off. "I just remember him calling me."

Taylor tried a few more times, but Nixon-Joiner insisted she couldn't recall. Before she left, Taylor asked why she had lied so many years before.

"I think I was a little, I was really upset," she said. "A little fear. You know, I don't know, that's all I can say."

As soon as she was away from the station, Nixon-Joiner picked up her mobile phone. "You are not going to believe this," she said when her sister picked up.

Nixon-Joiner recounted the interview for her sister in detail and the two women discussed whether she should get an attorney.

"I know the man wasn't right," she lamented. "If I knew then what I know now, I would have never married him."

Another thing she didn't know: A police officer was listening in on the conversation.

Taylor had persuaded a judge to approve a tap on her phone as well as her ex-husband's.

He hoped the surprise questioning about Browne's slaying would prompt her to call Nixon.

Days passed. She never called.

Homicide Bureau log entry - travel request

Taylor, like Edmundson and Morgan before him, decided he had to confront Nixon.

On a January morning in 2011, he boarded a plane for Oregon.

After Browne's death, Nixon's career stalled. The lieutenant worked 10 more years, but was not promoted again. He and his third wife moved to Salem, 60 miles from Portland, where they lived in a house in the woods outside of town.

Taylor and his partner waited in the city's only police station as officers went to fetch Nixon with a warrant Taylor had brought. Like the one Taylor had obtained for Nixon's ex-wife, the warrant required Nixon to submit to fingerprinting and provide a saliva swab to compare his DNA to some found on Browne's clothing. Taylor hoped it would give him the opening he needed to get Nixon talking.

As he thought out his strategy, Taylor struggled with when he should reveal to Nixon that his ex-wife had done an about-face on his alibi. Do it too soon and Nixon might demand a lawyer and stop talking. Wait too long, and Nixon might catch on to the fact that Taylor was fishing and didn't have any hard evidence.

Nixon arrived. Taylor introduced himself and offered Nixon some water. When Taylor explained why he was there, Nixon cut him off.

"I don't have anything to discuss with you," he said, according to a recording of the conversation.

"You wouldn't be a little bit curious why this is coming up now — 22 years later?" Taylor asked.

"Let me tell you," Nixon said. "When this murder occurred, I was interrogated several times. I told everything I knew. And I've learned nothing new since then."

When Taylor tried to press ahead with a question, Nixon cut him off again.

"You know what? You're rude," he told Taylor.

"I'm sorry."

"No. No. No. You're awful rude."

Taylor grew worried that Nixon was wrestling away control of the conversation. He decided he couldn't wait any longer.

"Your ex-wife is no longer keeping her story line," he told Nixon. "OK? That's important for you to know."

News that his alibi had come into question did not appear to faze Nixon.

Taylor talked as if it was a given that Nixon would stand trial for Browne's murder.

"You understand that there are witnesses who will … give testimony that your vehicle, your Mercedes-Benz, was at her house," he said. "What I'm saying is that we've got you back at the scene. We're able to put you back at the scene. And then returning the next morning to stage an event — which was the discovery. Now, that's what the jury is going to hear."

"OK," Nixon responded. "All right."

"We both know how court goes," Taylor said. "There ain't a defense attorney alive that is going to allow you to get up on the stand and begin talking, because the only thing you can do is sink yourself more. That's why I'm here. This is your opportunity to either come clean or give me some explanation as to what went on … with Aleta that night in her home and how did she wind up that way."

Nixon didn't give any ground. Round and round they went, with Nixon answering most questions with, "I don't recall." At several points in the nearly two-hour conversation, he declared he was done talking, only then to keep going.

At one point, Taylor pushed an autopsy photo of Browne's beaten body in front of Nixon.

"You remember what she looked like?" Taylor said. "That's what you did, Fred. That's your work."

"What, what are, what are you doing?" Nixon asked, his voice now sounding tired and strained.

"I'm showing you your work," Taylor said. "I'm showing you what you're responsible for."

"What part of that work is mine?"

"Ahh, well, she looks dead to me."

Taylor eventually gave up. An officer took a saliva sample and a fingerprint, and Nixon walked out of the station. After a few days monitoring Nixon's phone lines, Taylor had the wiretap shut down.

Sometime later, he sent an email to Browne's brothers.

"I want you and your family to know that I reopened this case with high expectations, hoping I could bring closure to this tragic situation," he wrote. "I am truly sorry things did not work out the way I expected … but as we know ... it's not what you know. It's what you can prove."

After more than three decades on the force, Taylor retired and turned the case over to another investigator, who declined to comment for this article.

Reached in Oregon, Fred Nixon declined to comment. His ex-wife, Nixon-Joiner, also declined to comment.

Aleta Browne's slaying remains unsolved.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.