Pure folly? Precisely

- Share via

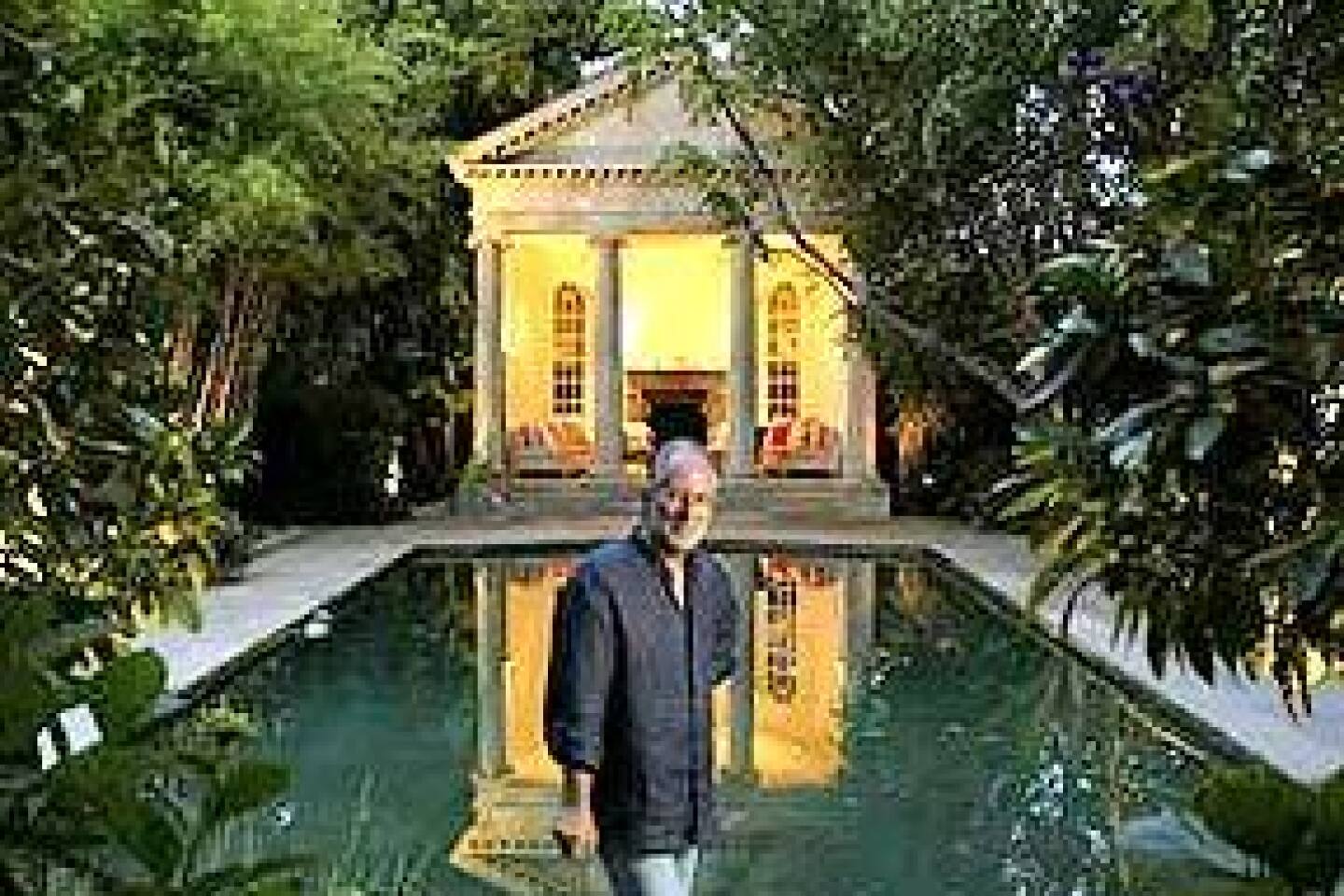

Richard SHAPIRO’S folly began, as many great things do, with the smallest of ambitions. Though the modern art collector and antiques dealer already had seven fireplaces in his 1920s Holmby Hills villa, he wanted an outdoor hearth. A place, he recalls, where “I could sit in front of a roaring fire during a rainstorm or on a cold winter night.”

Shapiro’s design for an alfresco fireplace soon soared into architecture on helium, a Greco-Roman portico based on the precise mathematical principles of 16th century Italian architect Andrea Palladio. “I thought it might be hokey,” the 63-year-old aesthete admits, “but then I accepted that what I was really doing was a folly.” This is less an admission of lunacy than a precise architectural description. Characterized as a fantastical, largely purposeless structure that springs from a passionate, often obsessive imagination, a folly is a building that references history and myth with unabashed drama and whimsy, often standing in discord with its surroundings.

FOR THE RECORD:

Royal Pavilion —An article in Thursday’s Home section on architectural follies included a photo caption that said the Royal Pavilion was in Brighton, Wales. Brighton is in England.

“They can take any form, any style,” writes Gwyn Headley, author of three books on the subject. “A folly is a state of mind, not an architectural style. Follies can even have a use or purpose, whether that was in the creator’s mind or not.”

Shapiro concurs. “Folly is defined as a nonsensical creation or activity,” he says. “I not only qualify, I take that as a compliment.”

History is on his side. In Europe, where they keep company with grottoes and other curious garden structures, follies have been traced back to the 16th century and had a heyday among the aristocrats in the late 1700s in Britain.

In that era, nobleman “Mad Jack” Fuller erected seven follies, including architecturally faithful renditions of an Egyptian pyramid and obelisks as well as a Greek rotunda. In 1761, John Murray, the 4th Earl of Dunmore, erected a 53-foot stone tower in Scotland carved to resemble a pineapple. Throughout much of the 20th century, Sir Clough Williams-Ellis turned Portmeirion in northern Wales into a village of rescued follies.

These are mere eye candy, however, compared to the Royal Pavilion built in the seaside town of Brighton by George IV, one of the most foppish of English monarchs. With five onion-shaped domes, the Indian-styled building with its over-the-top Chinoiserie interiors makes the Taj Mahal look timid and Grauman’s Chinese theater look chintzy.

In the U.S., people are more likely to think of follies as crassly commercial enterprises, such as the Luxor pyramid in Las Vegas, or as oversized folk art pieces, such as the Watts Towers in Los Angeles and the Bottle Village, a compelling cluster of 33 concrete and glass constructions built by Tressa Prisbrey in Simi Valley.

Shapiro’s folly is in the grand tradition of European eccentricity. At first he considered housing his outdoor fireplace in a modern structure, “four posts and a cover that would stand in juxtaposition to the Mediterranean architecture of the house,” he says. It would echo the way he placed minimalist sculptures and 20th century artworks amid the classical columns and ornate moldings inside his home.

It was a leap of the imagination to Neoclassicism. Having toured much of northern Italy, hopping from picturesque villas to village flea markets while buying antiques for his gallery on Melrose Avenue, Shapiro had become “smitten by history,” he says. “I want to touch the ages.”

Shapiro determined that he “would follow to the letter” the formula of Palladio’s Villa Chiericati, a building in Vincenza with a facade that Shapiro had visited and liked. Palladio, he says, is “one of those guys who is both ancient and modern. There’s spareness and efficiency in his designs. He took the basic proportions of the Greeks and Romans and updated it, making it grander and taller.”

A self-taught designer and architectural scholar, Shapiro drew up the plans for his engineer and contractors. “Once you lock into Palladio’s proportions, it’s very simple,” he says. “If the diameter of the column is X, their height has to be Y. If the height is Y, the building has to be Z wide.” When it was complete, he would make it look even more authentic by ever so gently destroying it. “I liked the idea of deceiving myself,” Shapiro says, “to look out the window and see an ancient ruin.”

Situated at the end of the algae-green pool that Shapiro loves to see covered in leaves, Shapiro’s Palladian portico exemplifies the architectural exuberance and excess of the folly.

From the bottom of its distressed concrete steps to the ornamental half-moon that sits at the peak of its triangular pediment, Shapiro’s Palladian folly stands more than 21 feet tall.

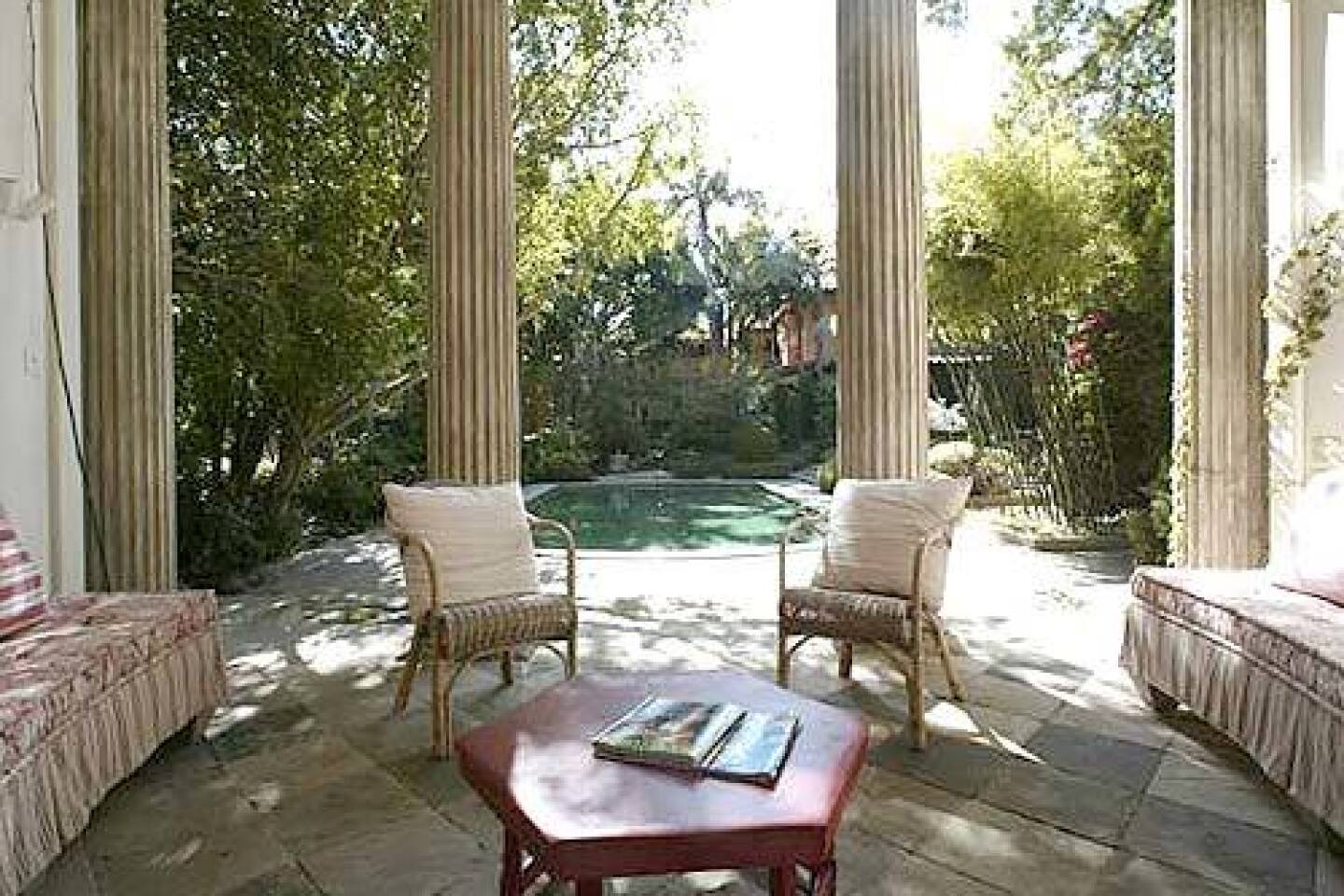

The four Ionic columns were made from redwood by Joe Madden of Madden Millworks in San Pedro. They were fitted with resin capitals and fiberglass bases slathered in lime and plaster, then painted by a Hollywood scenic designer to achieve Shapiro’s primary aesthetic goal.

“Decrepitude,” he proclaims. “I think filthier is better. If you study European construction, it’s not nearly as fussy and refined. Here, if someone gets a little flaking paint on their house, it’s a panic situation.”

To prove his point, Shapiro has been known to pour coffee and tea on paving stones and cement to give them a more aged patina. He is thrilled that the plaster in the portico has hairline cracks and vines are creeping across the walls. “I think it is a bit of a sore thumb, but that is softened by the foliage around it,” he says. “If I had it to do over I would destroy it even more.”

Behind the portico’s impressive facade, which could keep company with Washington, D.C., landmarks (complete with reflecting pool), the room has 13-foot ceilings and measures 19 feet across. Walls curve to meet a 19th century stone reproduction of a Renaissance hearth purchased in Antwerp, Belgium.

Shapiro covered the 275 square feet of interior space with “multi-blend, the cheapest, junkiest stone you can buy,” literally cutting corners by carving ragged-edged 14-inch squares that were laid in a diamond pattern. There are two daybeds of Shapiro’s design covered in a faded damask linen from Diamond Foam & Fabric in L.A., some worn wicker chairs and a $100 junk-store table he had painted red. Even the telephone — beige and decidedly analog — looks second hand.

The stucco exterior of the structure’s sides and back and the deliberately dialed-down décor are “very plain Jane,” Shapiro says. “All the money is in the facade.” He estimates that the tab for his folly ran to $100,000.

“People spend that kind of money on gourmet kitchens all the time and never think twice,” he says without a second thought. He acknowledges that spending this much on a Palladian portico might seem indulgent to the average homeowner. “Frivolous? Extravagant? Hollywood?” he asks, before answering with a smile. “I plead guilty. But I use it all day. I have my coffee and read the paper here in the morning, hang out by the pool and have drinks and dinner in the evening. It’s eccentric but in a nice harmless way.”

There were early indications that Shapiro might become an aesthete. Growing up in Burbank and Encino, Shapiro learned to paint from an artist who, in exchange, got medical care from Shapiro’s father, a physician. The Shapiros often visited the art galleries on La Cienega Boulevard during the ‘50s and ‘60s. “They stayed open on Monday nights,” Shapiro recalls. “It was something of an institution.”

The first house Shapiro purchased, a classic Spanish design, struck a chord, as did its terraced landscaping created by a greens keeper of the Los Angeles Country Club. In 1986, as the prosperous owner of Budget Rent A Car franchises, he moved into his current residence. It had been owned by film and TV composer and jazz musician Peter Rugolo, who had a Picasso-inspired mural painted on the bottom of the swimming pool.

Back then, Shapiro says, he was “living a Jekyll and Hyde existence.” After renting cars all day, he would come home to paint or go to meetings at the Museum of Contemporary Art, where he sat on the board. In the early ‘90s, he cofounded and designed the Beverly Hills restaurant the Grill.

During a brief retirement, he also filled his 8,500-square-foot home with antiquities, centuries-old furniture, modern art and the occasional 20th century piece, including a Gio Ponti secretary cabinet decorated with classical architectural motifs by Piero Fornasetti. It is a sophisticated mix: a fragment of an ancient marble sculpture shares a foyer decorated with the twisted remains of an automobile that form a John Chamberlain sculpture.

In design, Shapiro emulates the European sensibility. “Their approach to decoration and art is unrestrained,” he says. “They are very comfortable taking risks. They throw seemingly disparate items together in a joyous, almost naive way, and it always seems to work.”

He describes his home as “studied clutter. It’s not chaos. There is classical symmetry and I do like pairs, columns, things that frame a doorway. I like announcing a room that way or having a strong piece of art as a focal point. The objects that create drama must have soul and substance. They cannot be gratuitously beautiful or colorful, a cheap thrill.”

Shapiro’s folly began to occupy his mind about four years ago. After six years of retirement and a divorce, he was “bored out of my skull, just vegetating.” In 2002 he renovated a former pet supply store and opened Richard Shapiro Antiques and Works of Art. Last year he designed a furniture collection, Studiolo, comprised of iron and steel tables as well as upholstered pieces.

With his home, he took a long hard look at his yard. “I liked the idea of creating this world around me, where I wouldn’t know I was in Los Angeles,” he says. “I could be in Tuscany or the south of France. At first I thought it might look like a postmodern shopping center, but I decided if I went all the way with an authentic structure and really make it look like a ruin, that would be quite an accomplishment.”

And so it was. And when he looked at it, Shapiro was pleased. But not quite finished. Thumbing through a magazine earlier this year, he came across a photograph of the Chateau Marqueyssac in the Dordogne region of France, that featured an elaborate garden labyrinth made from topiary boxwood.

In a garden already filled with palms, Italian cypress and bamboo and fragrant with lavender, chosen for the color of the foliage rather than the sweetness of the flower, Shapiro embarked upon a botanical folly.

“I spent five days deciding where to plant 480 mature boxwoods and spent several hours a day for the next month trimming them,” he says. “This is not a complaint; I’m obsessed with doing it.”

The result was well worth it. Adjacent to a stone patio decked with gray spray-painted wicker chairs from Pier 1 Imports, Shapiro’s boxwood maze is a series of rounded undulating forms traversed by curlicue gravel walkways — an Alice in Wonderland garden as photographed by Tim Burton.

Shapiro considers the $25,000 he spent “a great bargain.”

“It’s such a singular thing,” he says. “It’s of the same ilk as the other folly.”

He has since moved onto a more quotidian project.

“I’m doing my living room over,” Shapiro says. “I don’t know what else I can do around here on a large scale basis, but I’m sure I’ll think of something.”

David A. Keeps can be reached at [email protected].

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.