What’s driving these LAUSD teachers to strike

- Share via

In Los Angeles schools, when there are no nurses, teachers help kids with broken bones and fevers. Psychologists talk children down from hurting themselves or others. Many students arrive at school knowing little English. Interventionists step in and give them an extra hand.

All are members of the teachers union, who work at schools at least eight hours a day and then often go home to take calls from parents, grade papers and write reports.

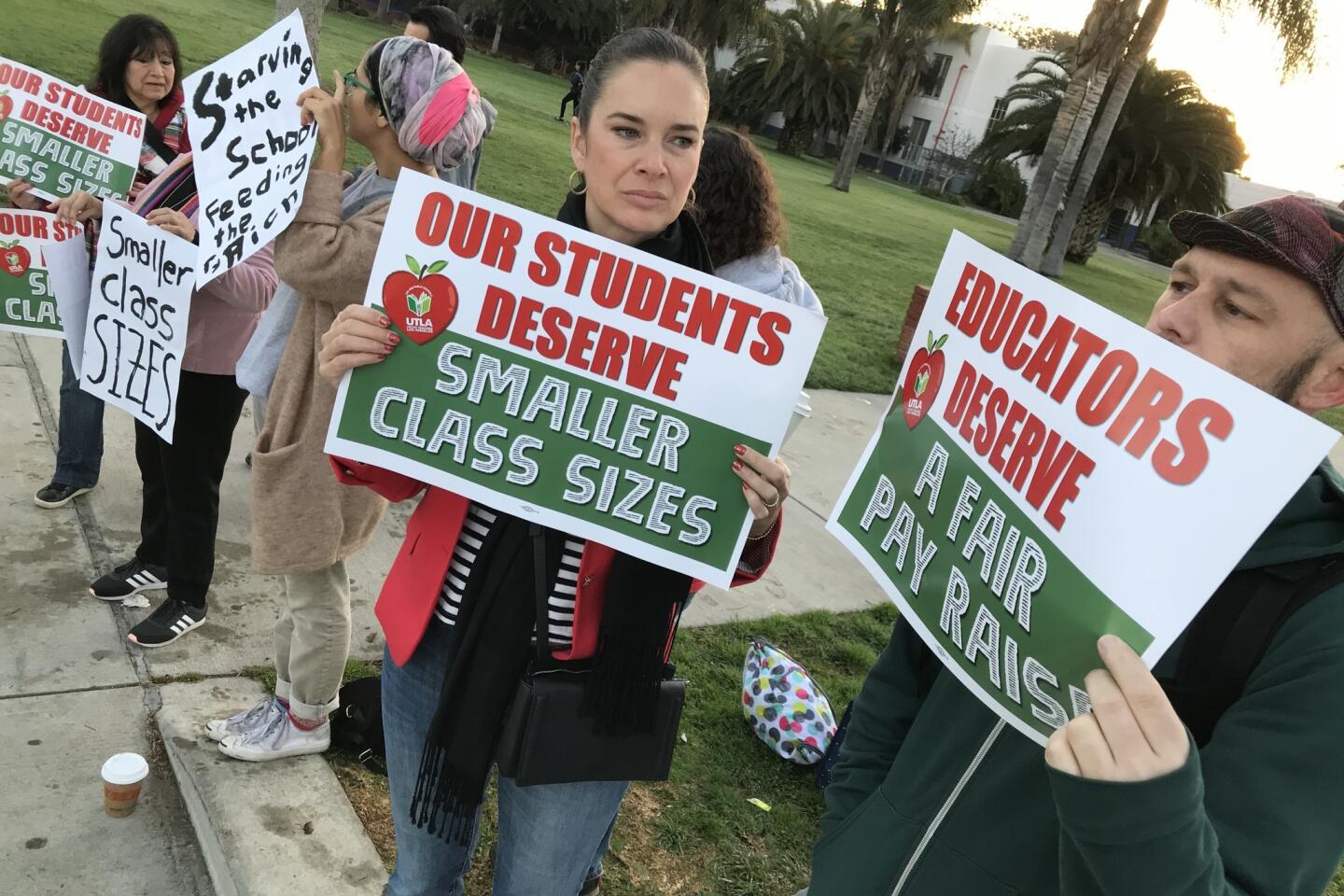

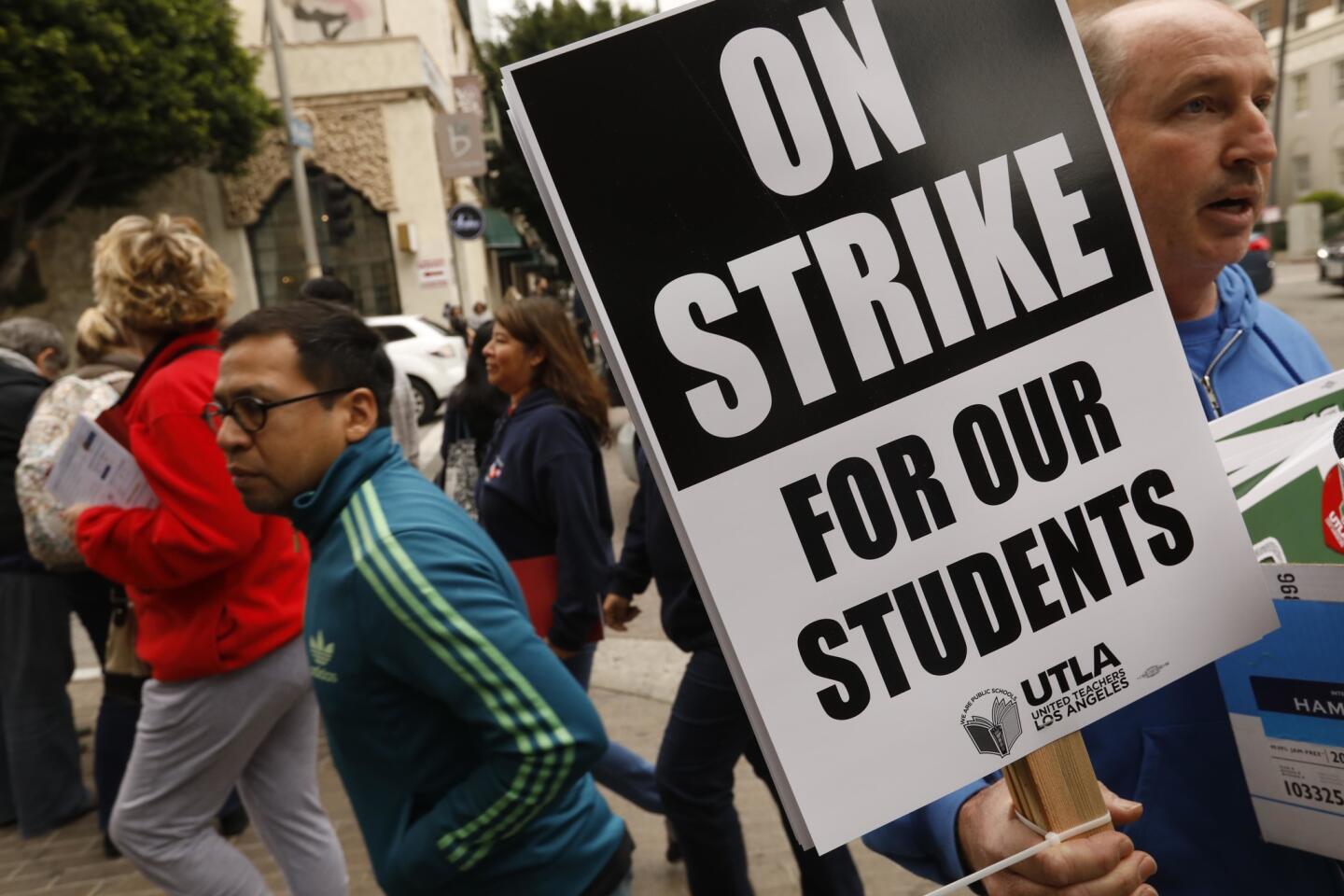

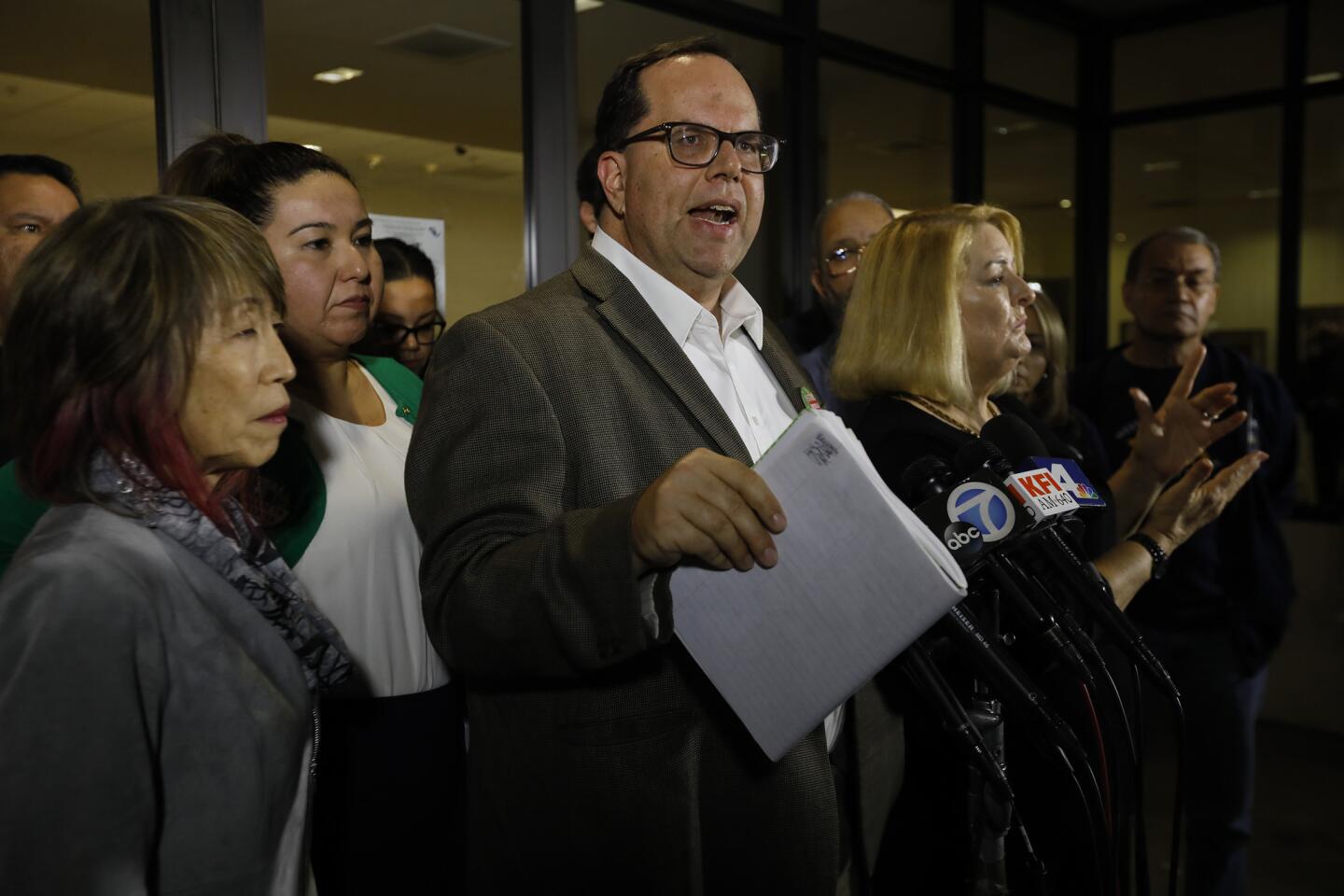

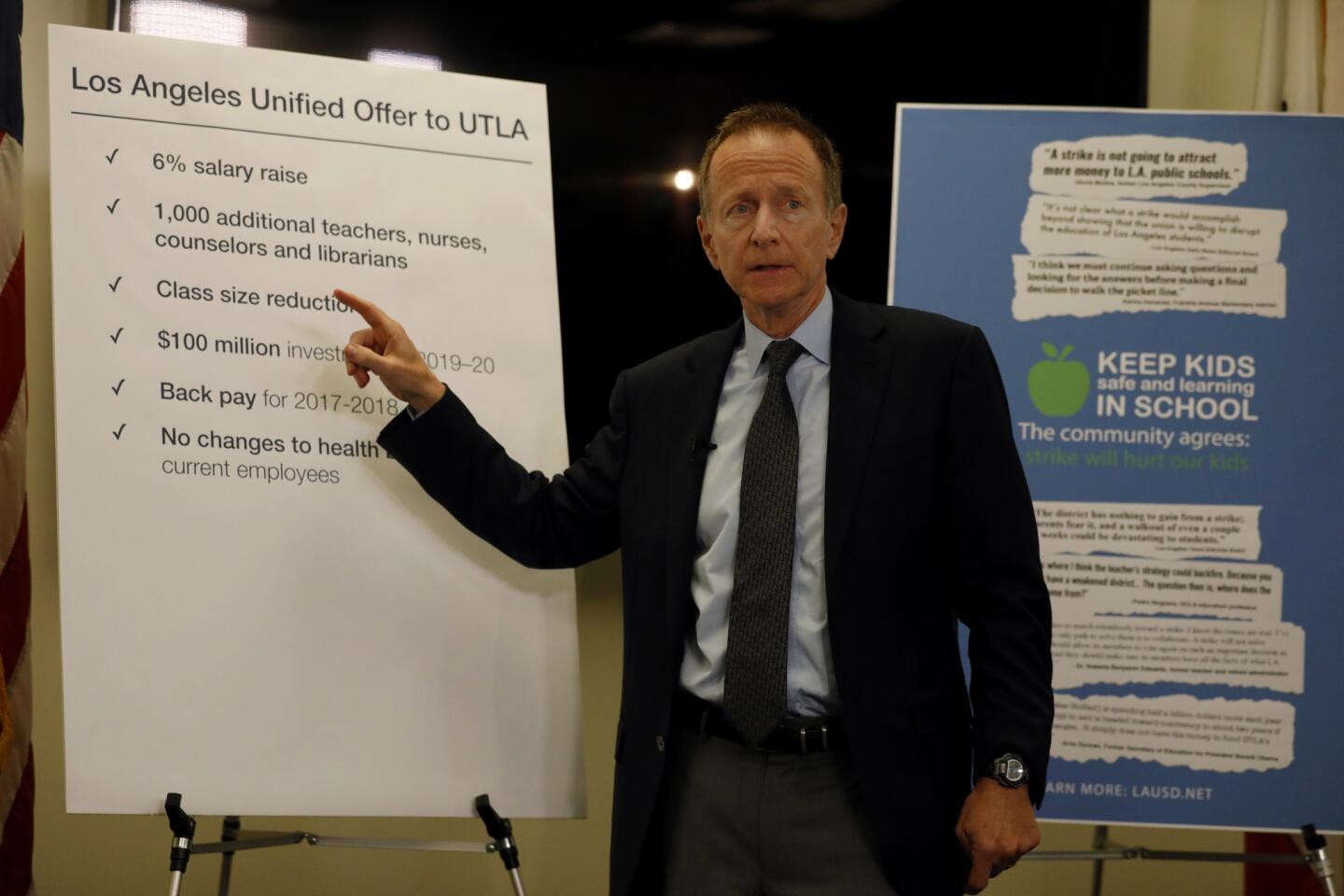

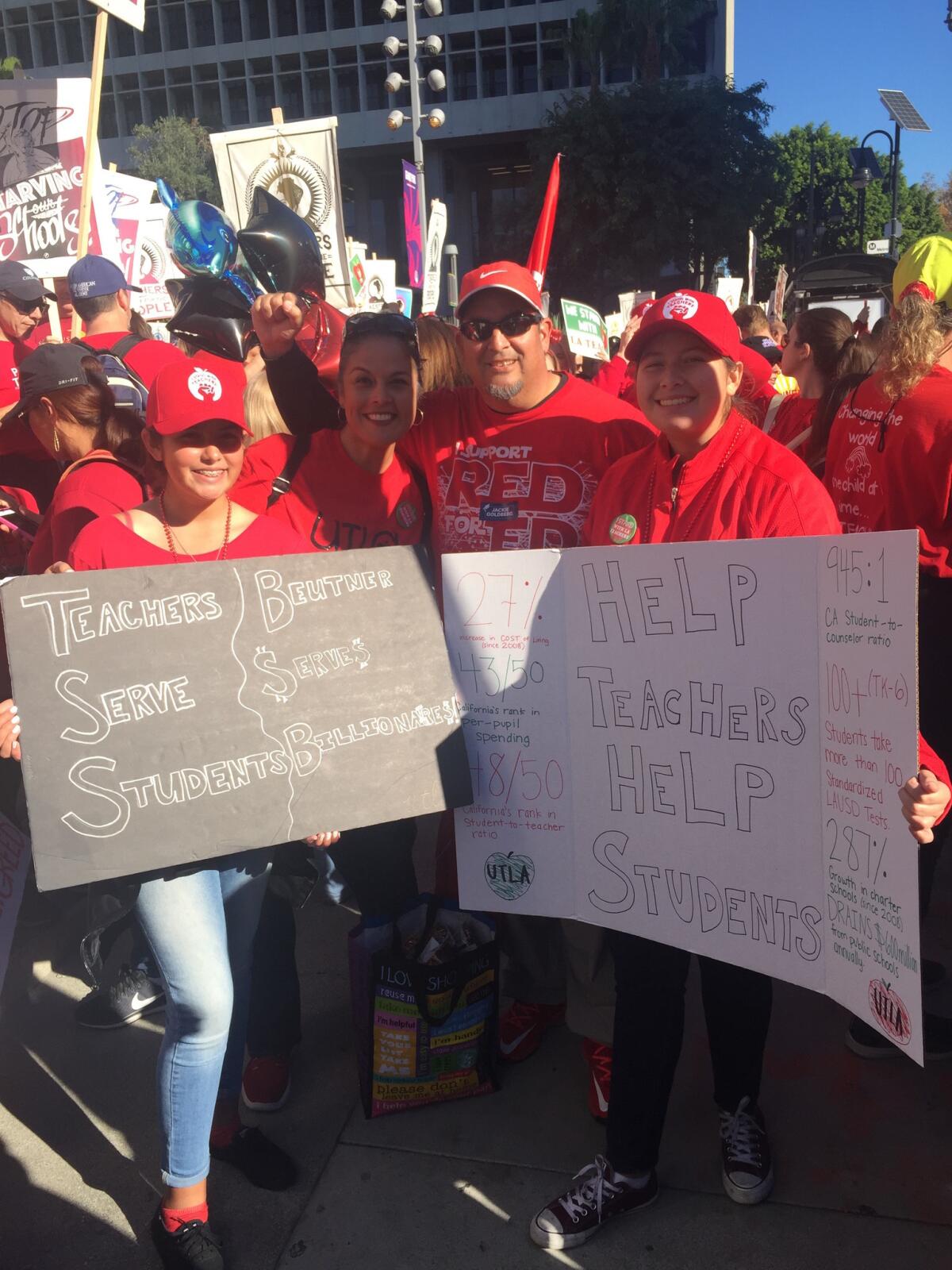

Much of the public discussion about a potential teachers strike Thursday has centered on the rhetoric from union and district leaders. The union wants higher pay, smaller class sizes, and more nurses, counselors and librarians in classrooms to “fully staff” schools. It wants more of a say in how charter schools share campuses. In speeches and slogans, those goals may seem distant and abstract.

But they aren’t for the 31,000 teachers union members inside schools, who might deal with students with many needs or teach classes so large that there aren’t enough desks to go around.

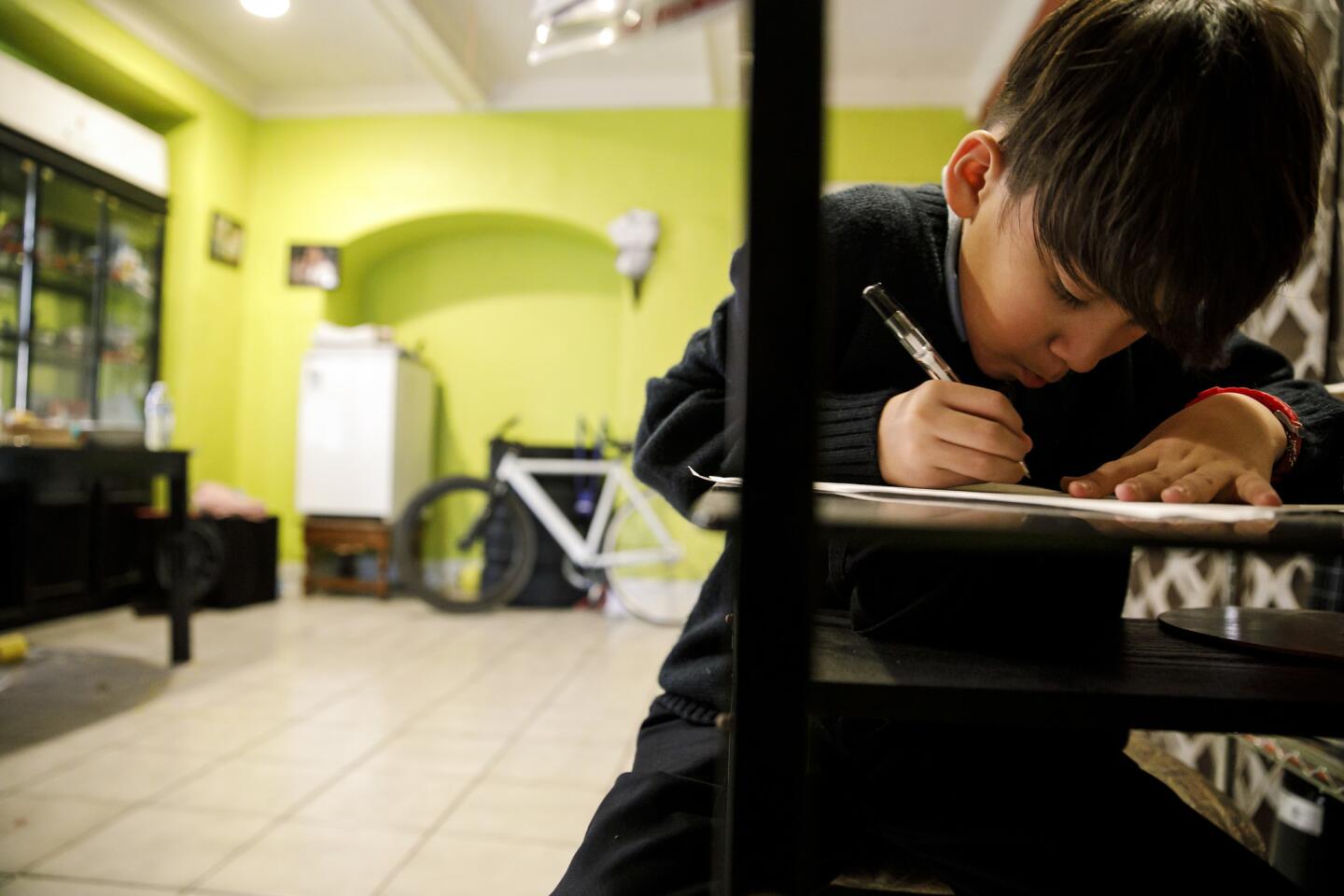

The nation’s second largest school district stretches across 710 square miles and includes South L.A., Bel-Air, the San Fernando Valley. Its population is mostly poor. Eight in 10 students receive free or reduced-price lunches. Nearly one-quarter of them are learning English.

Being a teacher in the system can be very challenging. An overwhelming 98% of voting members of United Teachers Los Angeles authorized a strike. Here is how some of them described why they are ready to walk out.

Fabiana Lamm, school psychologist

Fabiana Lamm is one of two psychologists at a San Fernando Valley high school with about 1,500 students. She asked that her school not be named in order to protect her students’ privacy.

Her job is to assess students for disabilities, write reports with her recommendations, sit in on individualized education program meetings for students who may need additional resources, including those with attention deficit disorder and autism, and provide counseling for 22 of those students.

Pictures in the News | Wednesday Jan. 9, 2019 »

“And then I get referrals daily for ... crises. Somebody’s crying. This kid wrote a note, ‘I want to kill myself,’ or ‘I’m very depressed.’ There’s all kinds of things going on in the high school,” she said.

Having more psychiatric social workers who can offer mental health support to students and handle crisis situations would help ease her load, she said. One of the union’s asks is for the district to have at least one psychiatric social worker, dean or restorative justice advisor for every 500 students.

A raise would also boost the morale of the 59-year-old, who has worked in the district 18 years.

“You keep making the same amount of money and the prices go up,” Lamm said. “So you feel like you’re not respected for what you do.”

Diana and Dan Castillo, coordinator and history teacher

All four members of the Castillo family spend their days in L.A. Unified schools. Dan is a history teacher at Banning High School in Wilmington, where Dahlia, 17, and Daniela, 14, are students.

Diana is the Title 1 and English learner coordinator at Harbor City Elementary. Her job is to allocate the federal funds that the school receives for its large population of low-income students, and to provide academic interventions for students who need them. Right now, the school uses a large chunk of its $333,000 in federal Title 1 money to pay for additional hours for its nurse, psychologist and librarian.

If the district fully funded some of those positions, the school could offer its students new classroom computers, science lab materials and outside programs to expose them to engineering arts programs.

“The computers that we have in the computer lab are so old that the IT department won’t come out anymore because they said they can’t update them,” Diana Castillo said.

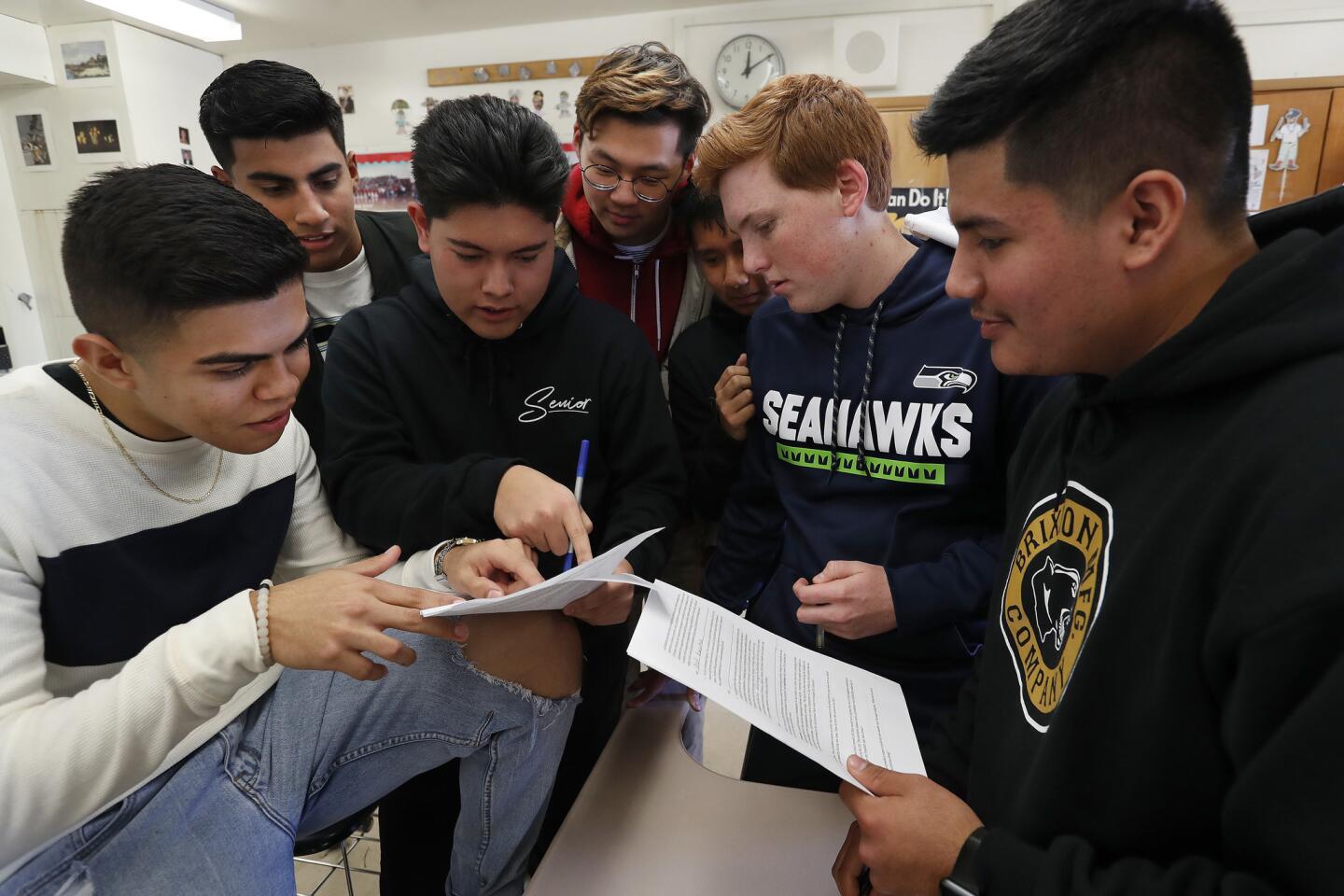

At Banning, Dan Castillo teaches in the magnet school, so his class sizes — in the low 30s — are slightly smaller than typical for the campus. He says he finds teaching that many students manageable. But his colleagues sometimes have to teach more than 40 students at a time. And Dahlia has been in some of those classes.

“There’s no space, you can’t walk around,” she said. “Some kids don’t even have desks,” she said. Instead, they perch on stools.

Dahlia is in difficult Advanced Placement classes with more than 40 students, and said she doesn’t get enough one-on-one time with teachers.

“We’re striking not only as educators but absolutely as parents,” Dan said.

The Castillos have more to lose since both parents work for the district.

“This is going to hurt us both financially,” Dan said. “We don’t have one of our spouses who works in a different industry who’s going to be bringing in money while we’re on strike.”

But if the strike hits major goals — smaller classes, more support — it will all have been worth it, they said.

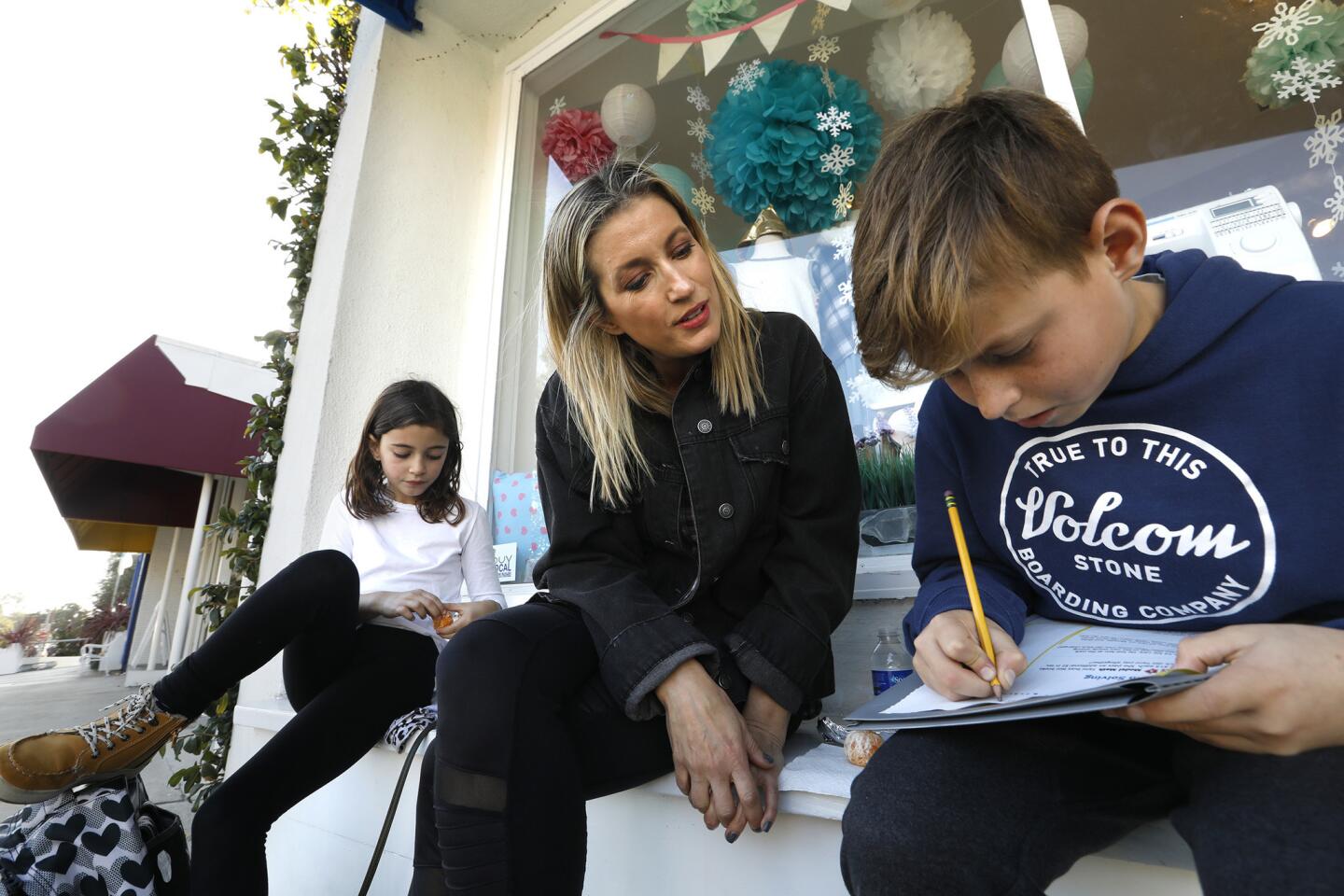

Kathi Sweet, first-grade teacher

The school district pays for each campus to have a nurse about one day a week. Additional days have to come out of school budgets. Often teachers have to take charge if students are hurt or unwell. Office staffers take temperatures and clean up scrapes. Schools have to call 911 for problems such as seizures that nurses might have been able to handle.

On the day that one of Sweet’s students fell and hurt her arm, there was no nurse on campus at Community Magnet School in Bel-Air.

The child said she felt OK, so the front-office staff sent her back to class with an ice pack.

“I can tell when somebody’s a little bit off, and I just thought that something’s not right about this,” said Sweet, 55, who has been a teacher in the district for 12 years.

She sent the girl back to the office and asked a parent to pick her up. The girl’s arm was broken, one of her parents later confirmed.

“It just sort of illustrates for me the need for someone with actual medical training on campus as much as possible,” Sweet said.

If that were true at her school, she could focus on teaching her class, she said, knowing that her students would be safe.

Reach Sonali Kohli at [email protected] or on Twitter @Sonali_Kohli.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.