From the archives:: Kovic Asks if Vietnam Taught Us Anything

- Share via

Ron Kovic comes toward me in his wheelchair before the doors of the elevator close. He reaches for my hand and squeezes hard. “Come on,” he says, and we slip into the third-floor Redondo Beach apartment where he’s been painting, writing, suffering through another war.

Kovic’s home is strikingly neat, as if this is his way of bringing order to the world. His canvas paintings hang from the walls like Polaroids of disturbed dreams. They hang next to photos of him with Oliver Stone and Tom Cruise, who played Kovic in the movie based on his searing, angry and sorrowful book, “Born on the Fourth of July.”

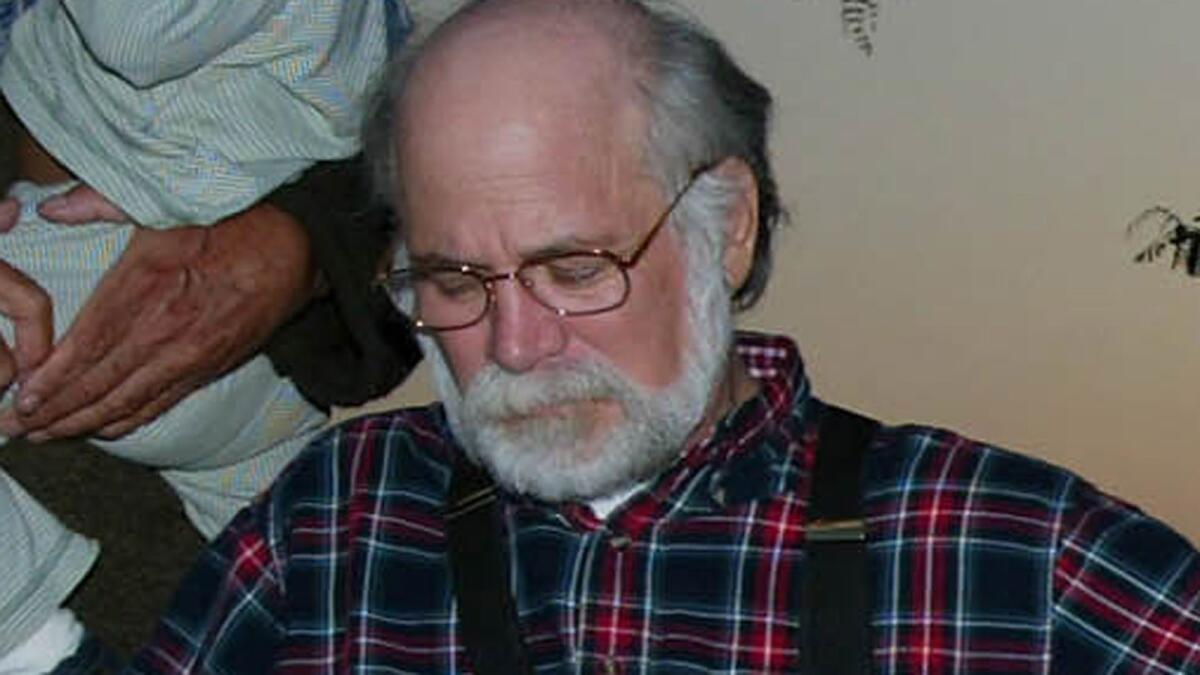

Kovic, with clipped white beard and wire rim glasses, apologizes for not answering my first call a couple of weeks ago. He was holed up here, in mourning and rebellion, as the three-year anniversary of Sept. 11 rolled around about the same time the toll of dead American soldiers in Iraq hit 1,000.

“What did we learn from Vietnam?” Kovic asks.

It all comes back to that. Kovic, 58, was shot on a Vietnam battlefield 36 years ago, and he has been paralyzed from the chest down ever since. When he gets into his hand-controlled vehicle and drives to a war protest, when he shifts his body onto his bed at night and closes his eyes, he has to believe his sacrifice has advanced the cause of peace.

I don’t have the heart to tell him we aren’t conditioned to learn from mistakes, but he already knows it.

“The president says the terrorists hate us because we’re free,” Kovic says, bristling at the simplification.

Let’s go get the terrorists, he says. But let’s admit there’s a backlash against decades of hypocritical U.S. foreign policy based on economic self-interest, and let’s admit this country has bedded a long line of despots.

“People forget that we supported Saddam Hussein to begin with,” Kovic says. “What’s been missing after Sept. 11 is a national dialogue about all of this.”

It’s missing in the presidential campaign too.

“Democracy is loud, it’s angry, it’s spirited, it’s passionate,” Kovic says. “I love this country and care about the safety of every American, and for our future security, we have to talk about what happened, and why, and go on from there.”

Kovic is writing a book on the subject. He’s also writing a fresh preface for the re-release of “Born on the Fourth of July,” drawing on current events.

“When I first heard it was 1,000 dead in Iraq, I went online and looked at the faces,” he had told me earlier by phone. “I scrolled down and looked at as many of them as I could, and I saw the same young faces I saw from my days in the service.”

He saw himself too. The gung-ho New York kid who was born on Independence Day, dreamed of playing for the Yankees and couldn’t wait to enlist with the Marines.

If you were strong, you answered the call without question.

You believed.

You believed everything they told you until you were surrounded by the screams of young men without faces or limbs, and it was only then that none of the justifications added up.

Iraq, 40 years later, has raised Kovic’s ghosts.

“People say, ‘Yeah, I support the war, I support the president, I think we should be in Iraq.’ Do they really know what it’s like to be there? To be hit by a bullet? To live with your wounds for the rest of your life? Do they have any idea what parents go through?”

Kovic leans forward, eyes burning.

“Will these people who support the war be there when these soldiers come home? Will they be there on lonely nights five years later, 10 years, 20 years later? Will they be there when they’re homeless because their lives have been ruined, or they’re in prison because they were never able to adjust?

“I’m glad President Bush didn’t have to suffer the way some of us did. I’m glad he didn’t get shot and end up in a wheelchair and suffer all the awful consequences. I know what it means. I’ve been on the battlefield fighting for my life when another Marine came up to save my life and was killed.

“I know what it means to come home to a government that isn’t prepared for all the wounded. I saw paraplegics and quadriplegics. I remember it, I can smell it and I will never forget it.

“This is a war we should never have fought to begin with, and it’s becoming a catastrophe and a mirror image of Vietnam. Another guerrilla war, another senseless quagmire.... It can only make us greater targets of terror, and it can only harm the soul of America.”

Kovic takes off frequently on these flights of rage, then almost seems to pull himself back. Don’t get him wrong, he tells me. He’s not a cynic, because he can’t afford to be.

“I feel a lot of energy,” he says. “This is a great challenge.”

He looks down toward frail bent legs, smiles and says:

“How can I turn this into something wonderful? Victorious? It’s important for me not to be a victim. Dignity over despair is what I tell myself.

“Dignity over despair.”

Kovic takes me on a tour of his apartment. In the dining room is an abstract scrawl that might be called a self-portrait for its sadness and hope.

“Look to the sky,” say the painted words, “when the tears of life are driving you wild.”

Kovic leads me out and toward the elevator. He asks about my wife and daughter and says he’s always wanted to get married, but hasn’t found the right girl yet.

Out front, he is on the porch as I walk away, thanking me for coming.

I get into my car and open “Born on the Fourth of July” to the first page:

I am the living death

The memorial day on wheels

I am your yankee doodle dandy

Your john wayne come home

Your fourth of july firecracker

Exploding in the grave

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.