When childhood innocence and gang violence lived side by side in Boyle Heights

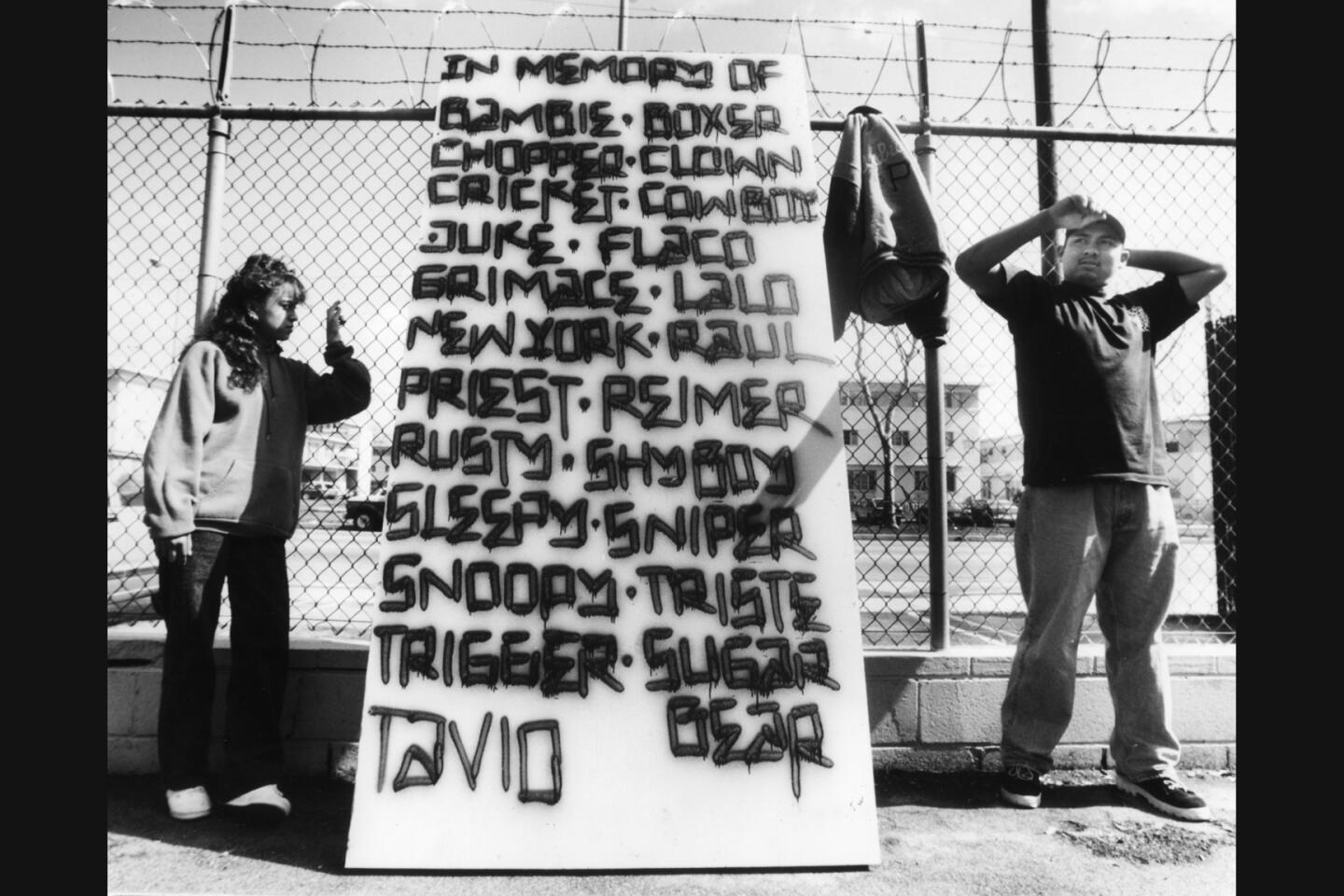

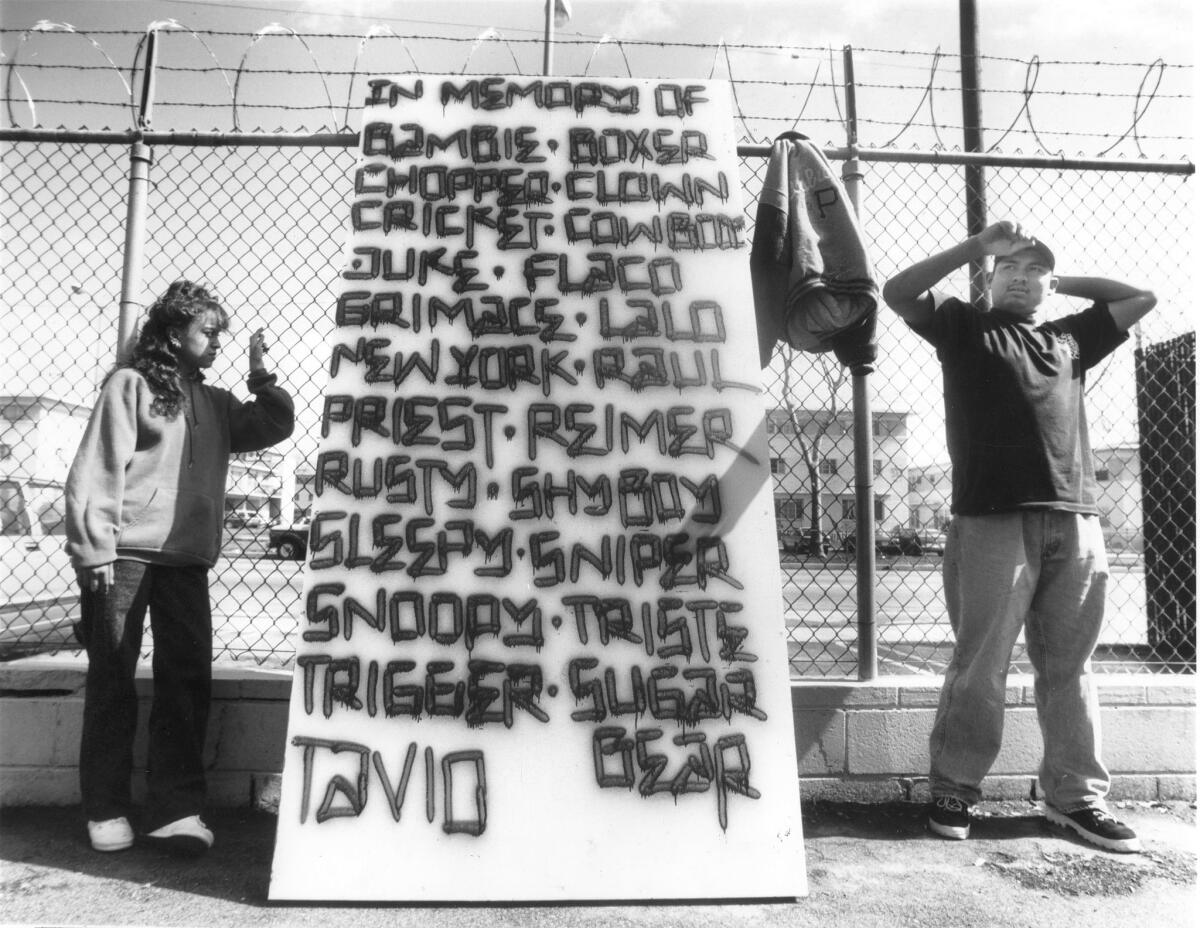

Artists Erica Parra and Joe Diaz in 1994 with a segment of a wall commemorating the deaths of gang members during the previous six years around Boyle Heights’ Pico-Aliso housing projects.

- Share via

In the 1980s, my boyhood best friend in Boyle Heights and I chatted about gangs. Particularly about starting one.

The idea was absurd since me joining a gang was a little like Potsie from “Happy Days” driving south of the border and becoming a hit man for a Mexican drug cartel. It wasn’t in my hard-wiring, nor did my life experience lend itself to me going from a bookworm to “Smiley,” vato loco at large.

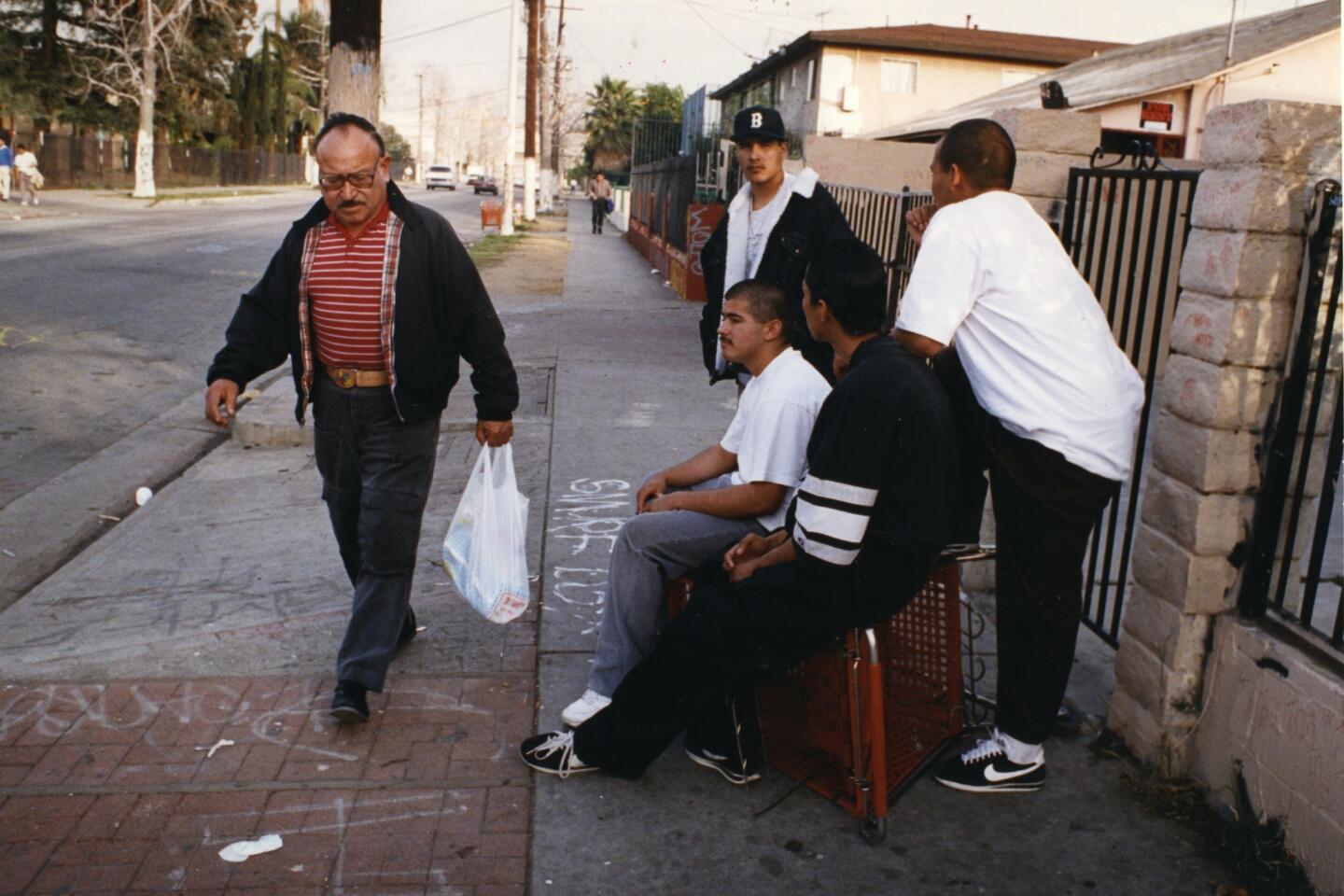

But there was something almost approaching mainstream about gangs a generation ago. Starting even something that weakly mimicked a gang — minus the hardcore commission of crimes, getting shot at and arrested — didn’t seem like the craziest thing ever. At the time, gang members didn’t try very hard to hide the fact that they were gang members. They hung out in corners and on stoops, and advertised their loyalties with tattoos inked to their visible skin like NASCAR racers.

Gang members were part of the scenery, like the shrubs finely coated by the freeway emissions from the nearby East L.A. interchange.

My friend Jesse recalled that he, his uncle and a couple of other kids from the neighborhood formed a group called the Rebels.

“We would have never formed that group if there were any real gang around us,” he said. “I think it was more like an identity for the group.... It didn’t last very long. Once we heard there was a club called the Rebels out of Rosemead and they were going to come down and kick our asses.”

But in fact, there were real gangs around us. They just hadn’t fully breached the core of our particular little neighborhood on Pomeroy Avenue, just a block from L.A. County-USC Medical Center. The closest we had to a resident gang in the 1980s were the Lord Boys, named after Lord Street — “altar boys in comparison to some of the killers running other streets and blocks ... beyond the wall,” Jesse recalled.

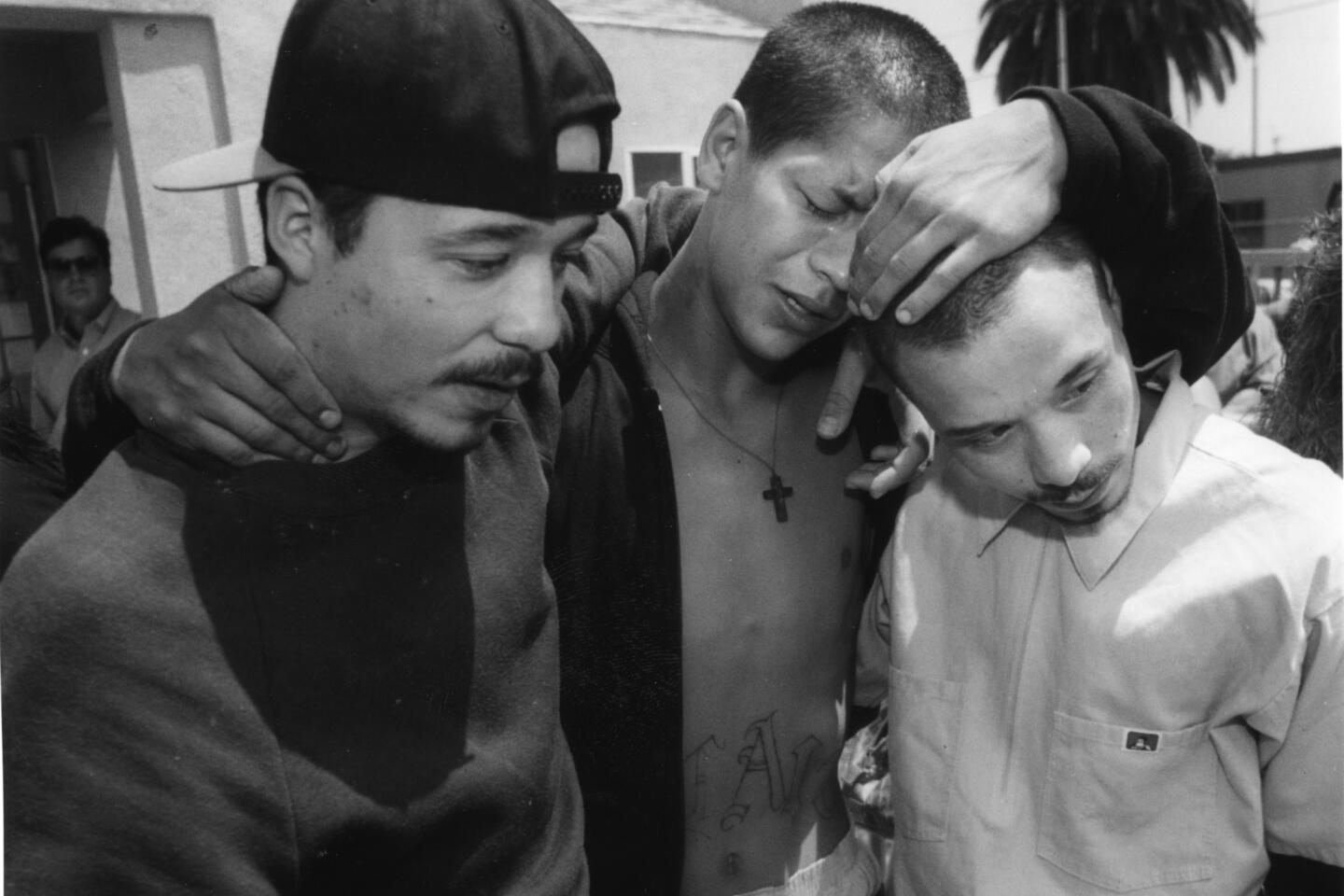

Beyond that figurative wall was an L.A. that was revving up for the bloodletting that was the early to mid-1990s, when more than 2,000 were killed in the county some years, mostly from gang violence. Our neighborhood, which Jesse described as “a little oasis or safe harbor” from the killings going on just around us when we were boys, was not spared from the escalating bloodshed.

There was Beto, who got called from the curb on Mark Street around the corner, only to have the top of his head blown away from an idling car; he took deep, gulping breaths on the concrete like a fish pulled out of the water. There was Orlando, who was fatally shot outside a liquor store on Marengo, just around the other corner. They were still children, just as Jesse and I were beginning our crawl into adulthood.

A drug dealer named Hugo had moved in and he had ties to a gang called Diamond Street. Hugo had a sort of Pied Piper effect with a few of the boys in the neighborhood.

“My brother and his friends went looking for trouble,” Jesse said. “And some paid with their lives.”

Growing up, the virtually public sale of crack cocaine was not terribly unusual in our neighborhood, just like in a lot of other places. It wasn’t a big secret who on the block was selling drugs.

Across the narrow street from my home, an old lady ran a dilapidated store. Doña Maria had taken a liking to our Irish setter dog, Rocky. She would give me a bucket of slop — stale tortillas, leftover soup and other odds and ends — to give him. Looking back, walking the few steps back across the street with that smelly, messy gift disturbed me more than the casual drug dealing or the sound of gunfire that rang out at night or the sirens from police cruisers and ambulances racing to the hospital.

Now, there are still gangs and gang members, of course, but the eyeball test will tell you that their numbers are diminished. The overt gang members who boldly threw hand signs and who practically wore their shaved heads, tattoos, their Nike Cortez sneakers and other ever-changing attire like a work uniform are, to a significant degree, a thing of the past. In neighborhoods from Boyle Heights to Watts, homicide rates have declined sharply since the 1980s and 1990s.

L.A. gave the world gangsta rap and endless movies about gangs like “Boyz n the Hood” and seared the almost cheerful-sounding term “drive-by” into the American vocabulary. There’s almost certainly a whole array of reasons that gangs have declined, but one of the simplest may be that being a gang member just isn’t seen as being as cool to kids as it was. It’s hard to imagine my friend Jesse, his uncle and friends or me ever even joking, circa 2016, about starting a gang.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

You may say that gang members are just not as out in the open as they used to be. But you’re fooling yourself if you think that doesn’t matter. If you remembered what it was like to walk past them as they hung out on street corners and in front of your homes, you know that such things do matter.

When I was a boy and then a teen, we all hung out on the street. It didn’t matter if you were a good kid or a bad one. We played bike and ball tag or football in the middle of Pomeroy Avenue, just feet from walls scrawled by the State Street gang, which was based just to the east. We walked along the railroad tracks behind our homes to Hazard Park like Mexican American versions of the kids in the movie “Stand by Me.”

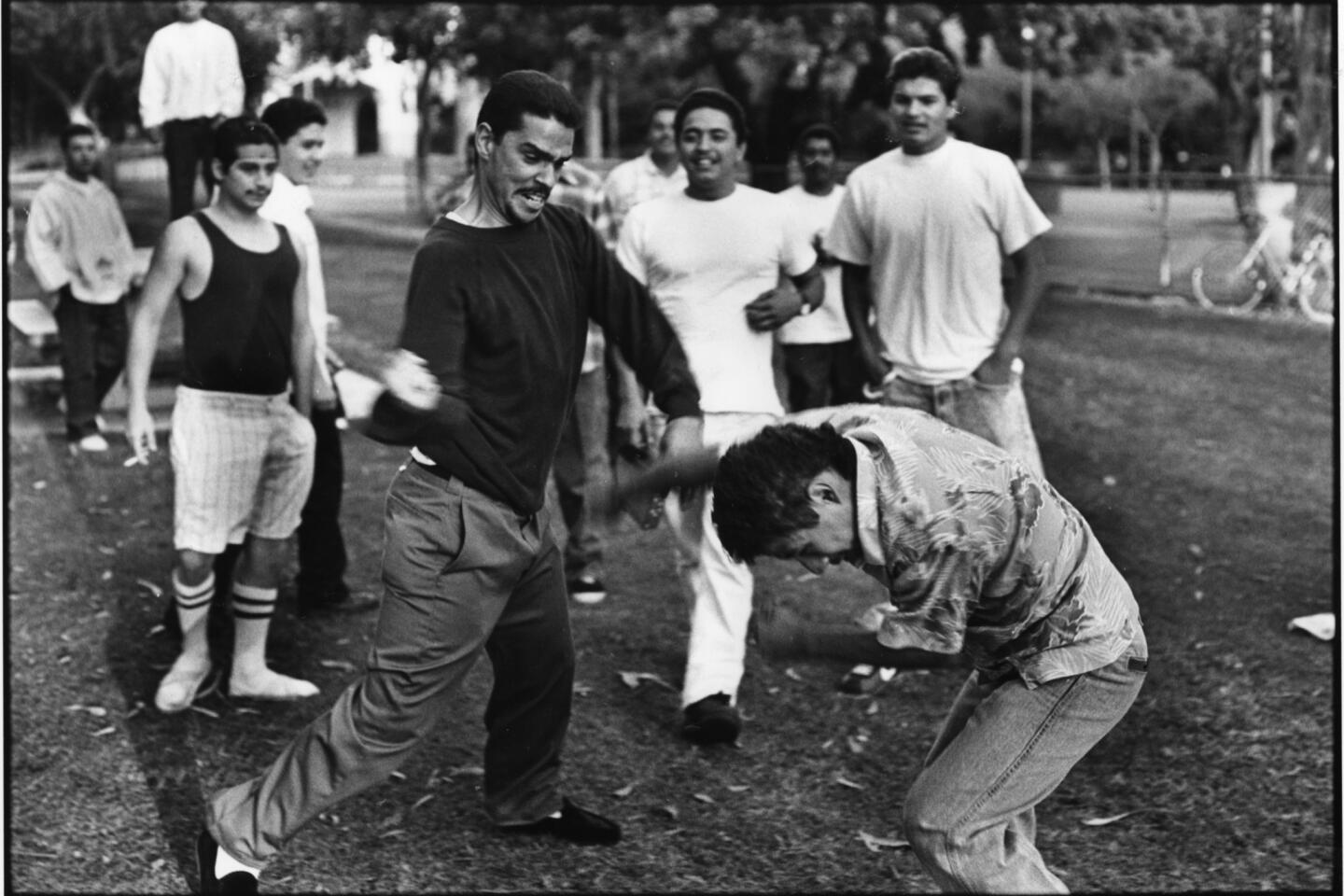

Jesse would go with other boys from the neighborhood to play tackle football in other neighborhoods — sometimes against kids who were definitely in gangs. Except for one time, when a fight broke out and people rushed the field — some with guns — he said the games were peaceful.

My mother still lives on Pomeroy Avenue. My dad died of cancer in the little stucco house we grew up in with the pomegranate tree and rosebushes and the vague outlines of a koi pond that my little sister built before she died, age 22, just a block away, struck by a car.

The neighborhood is quiet — in more ways than one. Crime has plummeted since I was a kid. And yet there’s fewer people living their life on the street, talking to one another or playing games. It was as though the fauna of the neighborhood went silent. If one day I saw a group of children playing football on Pomeroy Avenue, I would think: What is going on? And, circa 2016, I’m not sure I’d be OK with my daughter and son playing in the street the way my brothers and sisters and my friends did so casually in the 1980s.

Murder will never go out of business, but one can imagine that some of the people who died back when Jesse and I were very young maybe wouldn’t have now. The 1980s and 1990s could be cruel, and many of the deaths weren’t gang-related: There was my next-door neighbor Cathy who committed suicide while under the influence of drugs. And there was the father of one friend who shot dead the father of another just down the street.

But there was also something liberating about being a boy, playing outside and not being cooped up in your home, heedless of the grim statistics because you were so very young and didn’t know any better.

As for joining a gang — real or a naive facsimile — my older brother would have ridiculed me into abject shame and my mother would have pulverized me.

ALSO

Parents wrongly put on a child abuser list will get $4.1 million to settle their suit

These 2 teens with similar backgrounds took very different paths to college

After an ugly brawl, Sylmar High students walk out of class and call for unity

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.