- Share via

This story is part of Image issue 10, “Clarity,” a living document of how L.A. radiates in its own way. Read the full issue here.

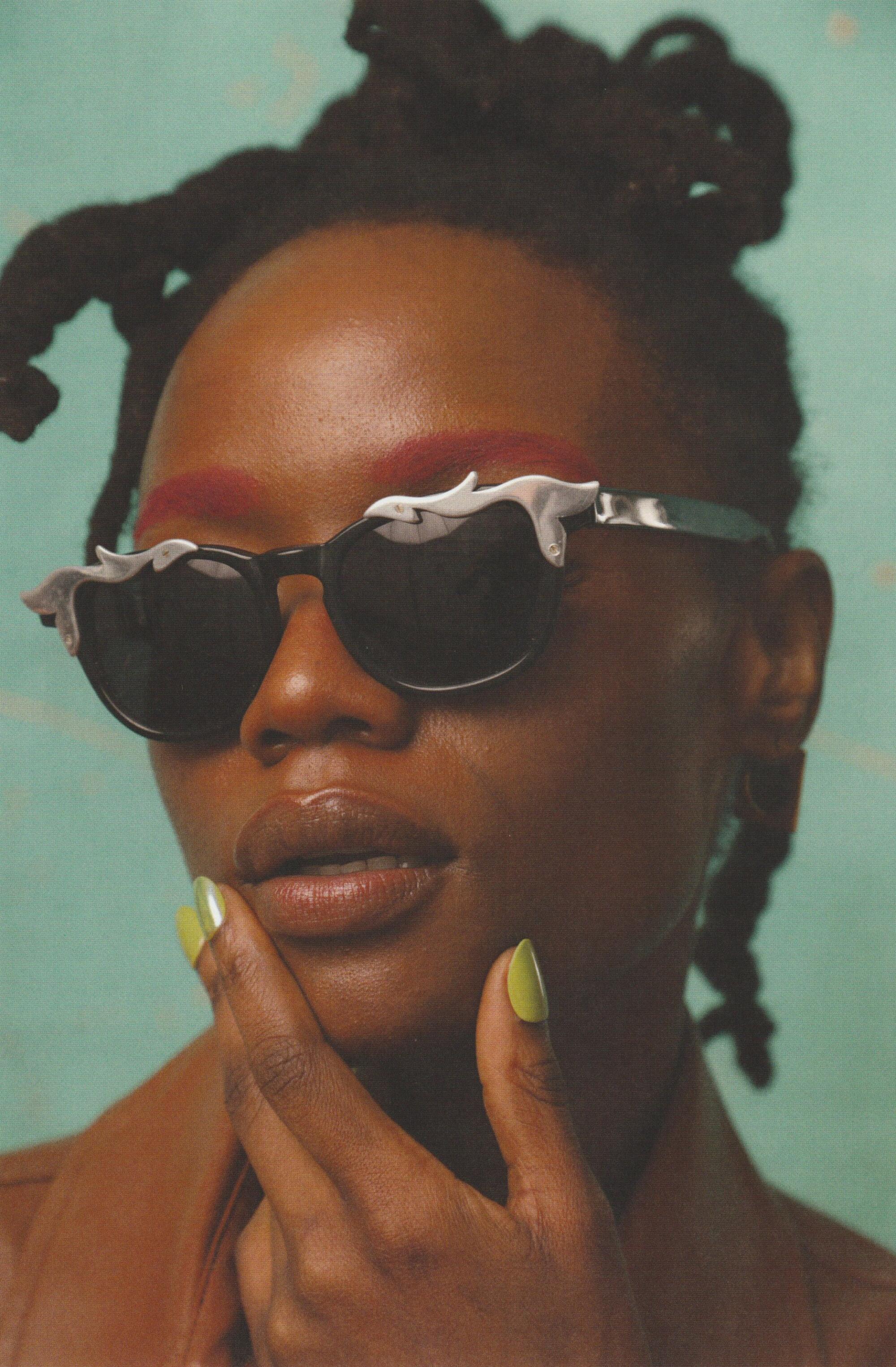

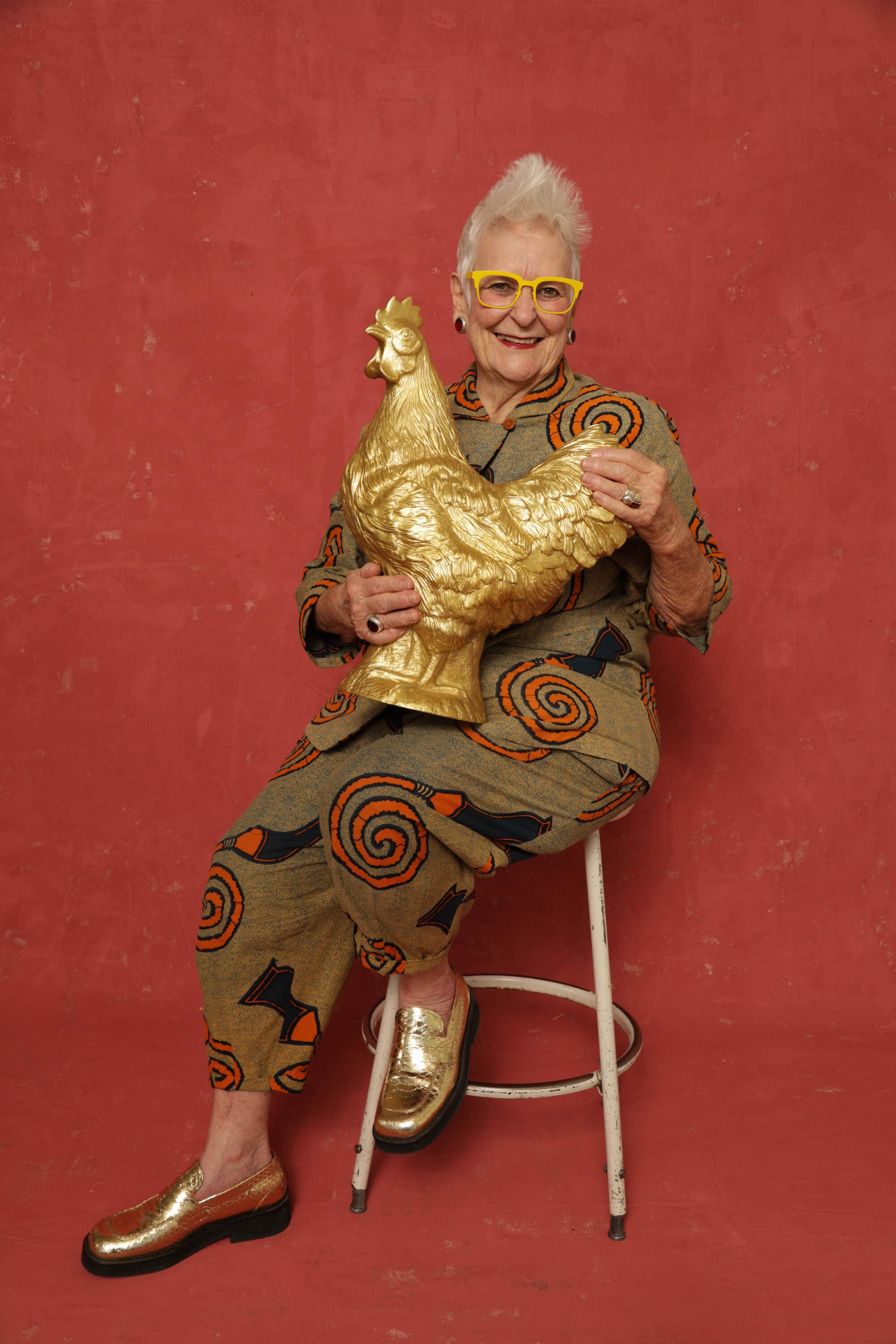

You haven’t truly made it in Los Angeles if you’ve never been in an l.a.Eyeworks ad campaign. Which is to say I haven’t made it, because I haven’t. The aesthetic of the ads is deceptively simple: a dramatically lit face shot up close and framed by one of the company’s iconic glasses. At the bottom of the ad is its succinctly stated ethos: “A face is like a work of art. It deserves a great frame.” Artists, actors and leading lights of the avant-garde have been immortalized in these ads across five decades. Debbie Harry, RuPaul, Pee-wee Herman, Andy Warhol, Iggy Pop, Grace Jones, Gregory Hines and countless others have posed for Greg Gorman since 1981.

By l.a.Eyeworks’ count, it has photographed more than 200 people, some of them famous like the aforementioned list of luminaries, and some just regular people with remarkable faces. Without trying, l.a.Eyeworks has become a local institution, a clearinghouse for the creative elite and a symbol of queer culture in the ascendant.

To wear a pair of l.a.Eyeworks frames is to immediately signal to people around you that you don’t just want to stand out; you need to. I’ve tried on its glasses numerous times, and there’s still a voice that lingers in my brain saying: “Are you sure you can pull this off?” The sharp angles, odd shapes and striking hues that l.a.Eyeworks is known for could cause chaos on your face, but there’s an elegance and confidence that you can feel in the models who pose for the ads.

The frames are both an expression of pure opulence and a secret code word between likeminded individuals, signaling that you too have a sense of humor about yourself, that you too are different. Such is the sensibility of the city itself. This is a whimsical, impossible place. L.A. is miraculous, and it attracts miraculous people.

More stories from Clarity

L.A.’s lowrider aficionados explain why the car club plaque serves as a sacred language for the culture.

Artist Maggi Simpkins shows what it takes to cut it as a jewelry designer in the Diamond District.

Anwar Carrots outlines the future of streetwear collabs.

Julissa James gets to the bottom of what an L.A. night really smells like.

Dave Schilling searches for the holy grail of L.A. outerwear.

Georgina Treviño reveals that everything has a little jewelry language in it.

Many of those people, particularly LGBTQ people, come here because of l.a.Eyeworks’ ads, according to its co-founder Gai Gherardi. “I can’t tell you how many people came up to me and said, you know, we couldn’t wait to know who was going to be in the next campaign,” Gherardi told me over the phone recently as we reflected on the impact of her life’s work. “I get these really heartbreakingly beautiful letters from people who talked about having a tearout of one of our ads in their bedroom as they were growing up as the only queer person [in their hometown].”

l.a.Eyeworks couldn’t have survived the changing tastes of America without that connection it forged with its customers. For l.a.Eyeworks’ adherents, it’s not just a place to get glasses. It’s a place to feel seen.

Gherardi opened l.a.Eyeworks with her business partner and childhood friend Barbara McReynolds in 1979. They opened a storefront on what used to be a sleepy section of Melrose Avenue between Martel and Vista. They’d both come from Huntington Beach and found themselves in the optical industry during a time of intense growth, specifically in Southern California. Brands like Larry and Dennis Leight’s Oliver Peoples were popping up in more tony neighborhoods with fancier addresses, but l.a.Eyeworks planted itself in what would become a focal point of Los Angeles’ bohemian community during the ’80s and ’90s.

Who says you don’t need outerwear in your closet in L.A.? How to find the perfect jacket in a city of microclimates and many moods.

Melrose rents eventually skyrocketed, but l.a.Eyeworks managed to stick around. When a new store opened, Gherardi said, there was a sense that it was going to be “the demise of Melrose.” A lot of other stores shuttered. “But we weathered all those in this beautiful way.”

l.a.Eyeworks survived despite never selling out to an optical conglomerate like Luxottica. To walk into either one of its stores now is to be whisked back to something like a golden era of cultural relevance in the city: “L.A. Law” reruns, drapey Italian and Japanese tailoring, lunches at Spago and beautiful eyewear. All of that ’80s glamour feels like it’s roaring back into fashion, but what is truly timeless about l.a.Eyeworks is its steadfast commitment to inclusion. Its ad campaigns could feature comedian Louie Anderson next to Pam Grier or legendary John Waters muse and drag icon Divine.

Gherardi was at the Divine shoot that day and recalls her coming into the studio out of drag: no makeup, no wig, in an average-looking suit. “She came out three hours later,” Gherardi remembers. “I was waiting and when Divine came out in this fantastic pink sequined dress, tears rolled down my cheeks. It was the most transformative moment. And part of it was this overwhelming feeling of how everyone negotiates and navigates to beauty.”

Living in Los Angeles requires a perpetual chase of beauty, a quixotic attempt to reach goal posts that keep moving in front of us. One has to remain in a constant state of flux to manage to retain whatever it is that makes them beautiful, if they even know. Because the honorific “beautiful” is traditionally bestowed upon us by someone else, life is filled with moments where you hope someone will pity you with a compliment. And most of us are not actively looking at people with the intention of finding their beauty. The sheer number of faces we see every day in a city as big as ours become white noise after a certain point. How can you distinguish one from another unless that beauty is so undeniable? You’d have to assume the person is famous.

The Dodgers’ hat is bigger than baseball. The interlocking L-A is iconic, and to see it on someone’s head is to feel an instant kinship.

But l.a.Eyeworks has always said that beauty can come from anywhere, at any time, from anyone. That’s particularly important in the visual landscape of Los Angeles, with its cultural gatekeepers and mega-corporations reverse-engineering celebrities and selling their manufactured images on billboards, on mobile apps, onscreen in film. Celebrity is aspirational but elusive. It’s purposefully exclusionary, because not everyone gets to be feted in that way. Luck, genetics and all-consuming ambition are basically prerequisites. To sell products, you have to be someone other people want to copy.

l.a.Eyeworks, by contrast, doesn’t cultivate aspiration. By alternating celebrities with unknowns, it flattens the idea of fame. It says that a face is like a work of art, but it doesn’t qualify which kind of face. It’s every face. What it sells is not exclusive. It’s a universal sense of belonging. The glasses focus your attention on the eyes of the person wearing them — a person who deserves to be understood, as we all do. Every one of their portraits is about a deeply human, relatable feeling.

“This has not been self-conscious,” Gherardi says. “This is just inclusive of the things we love and the people we love, and the things that speak to us and how we speak back.” l.a.Eyeworks “grew out of that and it continues to grow out of a love for color,” she adds. “It’s magical.”

More stories from Image