Label finds rapper’s crime doesn’t pay

- Share via

Jailhouse rap has turned out to be a bust for Def Jam Records.

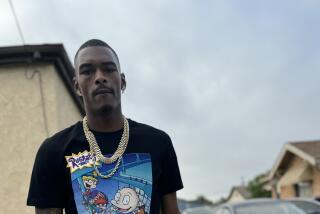

The New York label last year won a multimillion-dollar bidding war to sign imprisoned rapper Shyne. Before the release of his debut CD, “Godfather Buried Alive,” Def Jam made sure its new catch was everywhere -- in music magazines, in videos and on live radio interviews broadcast on top-rated hip-hop stations around the country.

The night before the album hit stores, MTV News aired an hourlong special on the rapper, whose real name is Jamal Barrow. The special, partially underwritten by Def Jam, was called “Shyne On.”

But rap fans apparently were turned off.

The album, released Aug. 10, flopped. In its seven weeks on sale, “Godfather” has sold 354,000 copies -- less than half what most hit rap CDs sell in their premiere week. In the latest seven-day tally, it sold just 15,500 copies and plunged to No. 68 on the national pop chart, according to Nielsen SoundScan.

Def Jam spent more than $4 million to sign, record and market “Godfather,” sources said. Based on sales figures compiled by Nielsen SoundScan, the company has recovered about $1.3 million of that investment. High-level sources at Def Jam said they didn’t expect the record to pick up steam at this point and were prepared to abandon the project.

Barrow seems to be the only one who profited from the ill-fated Def Jam deal. He received a $3-million advance.

Def Jam’s willingness to capitalize on Barrow’s criminal background to promote his CD may seem crass, but it is the kind of stunt that is becoming more common as record companies strive to remain relevant to consumers. Increasingly, the music industry has sought to refashion itself as the prime purveyor of not just music, but culture and lifestyle. With the encouragement of music executives, such artists as Britney Spears and 50 Cent have teamed up with corporate advertisers to hawk shoes, soda and video games.

When it comes to rap stars, music industry executives know that they’re selling menace as well as music. Criminality adds credibility, and in the case of Barrow, who is serving a 10-year prison sentence at the Clinton Correctional Facility in Dannemora, N.Y., for assault, it may have been more marketable than his talent.

“Buying into Shyne isn’t like buying into the normal hip-hop artist,” said Marcus Logan, a consultant who helped construct the marketing campaign for Barrow’s new release. “With him, the music is almost secondary.... We were selling his story, his credibility.”

Last year, Def Jam executives began visiting Barrow in prison and wooing him to join the label. Months later, in April, Def Jam outbid Time Warner Inc.’s Warner Music Group and Sony Corp.’s Sony Music Entertainment to sign the rapper, paying him the multimillion-dollar advance and agreeing to finance a joint venture label called Gangland Records.

Barrow, a former protege of Sean “P. Diddy” Combs, had previously released only one modest-selling album, a self-titled CD put out by Combs’ Bad Boy Records. Barrow’s fledgling rap career was interrupted after he was implicated in a Manhattan nightclub shooting in 1999. Witnesses testified that Barrow fired a pistol into the crowd, injuring several club patrons.

Barrow, who often raps about shootings and gang warfare, is ineligible for parole until 2009.

Most of Barrow’s vocals for the album were recorded several years ago, before he entered prison. Def Jam hired some of the industry’s hottest producers to create new tracks supporting those vocals. However, Barrow’s rap on “For the Record,” one of the album’s strongest tracks, was recorded this year over a prison telephone line.

Def Jam’s eagerness to sign Barrow also illustrated the major shift that occurred at its corporate parent, Vivendi Universal’s Universal Music Group. Just five years ago, the company banned the use of sexually graphic and violent imagery.

The company’s attitude toward rap began to change in 2000, after Universal bought PolyGram and took control of Def Jam, one of the raunchiest but most profitable rap labels. Gradually, music executives who had led the corporation’s crusade against sexually explicit rap music began to orchestrate the mainstreaming of “gangsta” rap imagery and help land corporate endorsements for such rap stars as Jay-Z and Ludacris.

Shyne doesn’t seem destined for such superstar treatment, which is OK with him. “Me, I don’t think about sales,” he said in a phone interview from prison on the eve of his CD’s release. “Milli Vanilli and Vanilla Ice sold millions of records. Record sales don’t capture what I want to be. This is my art. My lifestyle. What you see is my way of being.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.