California lawmakers vote to ban mandatory evictions for arrested tenants

- Share via

State lawmakers approved legislation late Wednesday that would bar mandatory evictions or exclusion for California tenants and their families based on criminal histories or brushes with law enforcement.

Assembly Bill 1418 combats local policies known as “crime-free housing” that can require landlords to evict tenants for arrests or prohibit landlords from renting to those with prior convictions. The bill would make many of these laws unenforceable, ending the practice in scores of communities.

The bill’s author, Assemblymember Tina McKinnor (D-Hawthorne), said that its passage advances the state’s racial justice efforts by stopping communities from using crime-free housing laws to exclude or push out Black and Latino renters.

“We want to make sure we keep Black and brown people in their homes and that [crime-free housing rules] are not used as an excuse for gentrification,” McKinnor said.

The bill does not affect landlords’ ability to initiate nuisance-related evictions or screen tenants based on criminal histories of their own accord.

AB 1418 was inspired by a 2020 Times investigation that highlighted the proliferation of crime-free housing policies across California, especially in communities with growing Black and Latino populations. Times reporting found that local governments have approved the policies even when crime rates were stable or falling, while the number of Black or Latino residents was increasing. The Times determined that in some areas crime-free housing rules were enforced against Black, Latino and other tenants of color in far greater numbers than their share of the population.

Nearly 2,000 communities in the U.S. and elsewhere encourage landlords to evict or exclude tenants who have had some interaction with law enforcement.

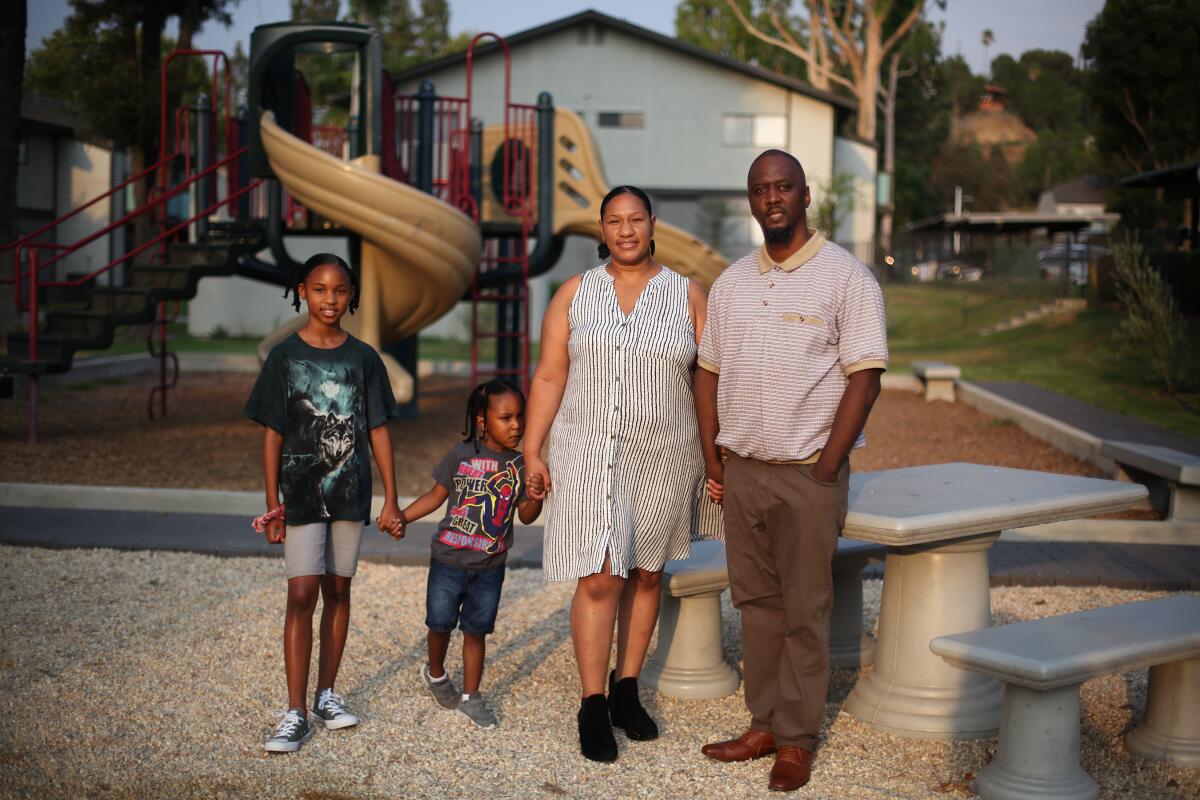

Terrance Stewart told The Times in 2020 that he faced constant rejections from landlords in Riverside, which had a strict crime-free housing ordinance, due to a prior cocaine dealing conviction. Stewart, who is Black, had been accepted to UC Riverside and had to resort to living with his wife and then-3-month-old daughter in another city a 90-minute bus ride from campus. Stewart’s problems finding housing in Riverside continued even after he graduated with a master’s degree five years later — nearly a decade after his drug conviction.

Stewart, now 42 with three children, testified in favor of AB 1418 during a legislative committee hearing earlier this year. With the bill’s passage, he’s planning to look for apartments in Riverside in neighborhoods with good schools.

“It’s just awesome that your pain becomes your ministry,” said Stewart, who works for Alliance for Safety and Justice, a national criminal justice reform group. “I’ve been so stressed out behind these ordinances.”

His involvement in the repeal of crime-free housing laws, he said, “makes me feel like life, it has a purpose.”

AB 1418 passed both houses of the Legislature without a dissenting vote in a committee or on the Assembly or Senate floors.

Gov. Gavin Newsom has until Oct. 14 to sign or veto the bill or allow it to become law without his signature.

Newsom’s position is unknown. His office previously opposed the legislation, citing potential costs for the state to reimburse localities for having to repeal their ordinances. But McKinnor has since removed a requirement for cities to strike their policies from their municipal codes. Instead, they could remain on the city’s books but no longer be enforced.

Newsom typically does not comment on pending legislation and his office did not respond to a request for his views on AB 1418.

Crime-free housing programs vary widely in California. Less severe ones include police training for landlords on criminal background checks and anticrime lease provisions. But some go much further.

A now-repealed crime-free housing law in Hesperia, a high desert city, required landlords to evict tenants and their families based on police suspicions they were involved in criminal activity on or near their properties. Before its passage, a council member described the crime-free housing law’s purpose as “to correct a demographical problem with people that are committing crimes in this community.”

Last year, the U.S. Department of Justice settled a lawsuit against the city and the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department that claimed Hesperia’s policy violated civil rights laws after a federal investigation found that Black renters were almost four times more likely, and Latino renters were 29% more likely, to be evicted under the program than white renters.

Hesperia and San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department will pay $1 million to settle a suit alleging discrimination against Black, Latino tenants.

AB 1418 is the state’s highest-profile response to unwind crime-free housing policies, a cause that has been gaining momentum.

In the spring, Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta issued formal guidance to all municipalities to ensure any crime-free housing laws complied with broader civil rights and fair housing regulations.

Over the summer, California’s Reparations Task Force called for repealing such laws in its recommendations for remedying the legacies of slavery and more modern government-sanctioned policies that discriminated against Black residents.

And this month, Riverside and San Bernardino, the two largest cities in the Inland Empire, which has been a hotbed of crime-free housing rules, voted to repeal their ordinances. San Bernardino did so as part of a legal settlement to a case challenging its program filed by legal aid groups — and joined by Bonta’s and Newsom’s offices — on behalf of low-income residents in the city.

How many crime-free housing rules AB 1418 would bar isn’t clear, but supporters believe the number is substantial.

The 2020 Times investigation found that 147 local governments in California — more than a quarter of the total — had enacted a crime-free housing law or advertised such training for landlords.

AB 1418 bans the most stringent crime-free housing policies that compel landlords to use criminal background checks to screen tenants, evict them for alleged criminal behavior without a felony conviction or evict an entire household when one member is convicted of a felony, among other prohibitions. It would allow voluntary training for landlords by city and police to continue.

A survey of roughly half the local governments in the state completed for the nonprofit National Housing Law Project found that the legislation would wipe away crime-free housing rules in 130 jurisdictions.

“This bill was intended to eliminate the common provisions that lend themselves most to displacement,” said Marcos Segura, a staff attorney at the National Housing Law Project, one of the principal backers of the bill.

Assemblymember Tina McKinnor (D-Inglewood) wants to ban strict “crime-free housing” laws. A Times investigation found those laws disproportionately affect Black and Latino renters.

AB 1418 has a wide-ranging list of supporters. Besides advocates for low-income tenants and legal aid organizations, the California Apartment Assn., the state’s largest landlord group, is behind the measure. The apartment association contends that cities shouldn’t have policies that require landlords to evict tenants.

“This is an inappropriate and objectionable mandate on the part of local governments,” association Vice President Debra Carlton said of crime-free housing laws in a letter of support for the bill.

Historically, crime-free housing policies have attracted strong backing from police and prosecutors on public safety grounds. But there are no listed opponents to the legislation.

Should Newsom sign AB 1418, it would take effect Jan. 1.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.